Can there be any black hole big enough that a regular sized star can pass through its event horizon unharmed?

-

6The answer of your question is not straightforward. It depends on the definition of black hole volume (there are several notions for this purpose). One cannot naively think about black holes like spherical balls in Euclidean space. So how do you define the volume of a black hole? How long does it take for the first part of the star to reach the singularity? (Compared to the time it takes for the last part of the star to enter the horizon.) After answering these, you can do the relevant analysis for a rotating black hole, including computing different components of relativistic tidal forces. – Ad Astra Jun 07 '21 at 12:39

-

2@AdAstra The time for the whole star to cross the EH is $\sim 2R_/c$ whilst the time to reach the singularity is $\sim r_s/c$. Since $R_ \ll r_s$ for any star that can survive the tidal forces then there would seem to be no issue. – ProfRob Jun 07 '21 at 13:20

-

1@AdAstra The volume of a black hole can be easily calculated. When measured in Kerr-Schild coordinates the volume is about $6,567\times (2m)^3 (m^3)$ – Deschele Schilder Jun 07 '21 at 13:31

-

2@ProfRob___"The time for the whole star to cross the EH is $∼2R_∗/c$ whilst the time to reach the singularity is $∼r_s/c$. Since $R∗≪r_s$ for any star that can survive the tidal forces then there would seem to be no issue." This is not bad, though it basically depends on the definition of the "volume" inside the event horizon, again. Assuming that you are dealing with the geometric interpretation of black hole volume, this response is sufficient (for this definition see this paper). I suggest you put that point in your answer. – Ad Astra Jun 07 '21 at 14:00

-

1@Barbierium___By what definition is that volume obtained? BTW, it is not as simple as you think. – Ad Astra Jun 07 '21 at 14:04

-

3For single-line questions like this one it is better to guide OP to the right question/answer rather than give it straight away. We should note this and consider in the future answers. They should ask a conceptual question here. On the other hand, the only way people could optimize the level of their answers is if the original poster provides some details about what is a simple level for him/her. – Ad Astra Jun 07 '21 at 15:32

-

3@AdAstra: The answer to this question doesn't depend on the definition of the volume of black hole (which, as you've noted, is undefined). – Jun 07 '21 at 23:20

-

Isn't that sideways? Can there be a black hole small enough might make sense… – Robbie Goodwin Jun 08 '21 at 02:35

-

1What do you mean, @Robbie? A small BH has very strong tides, so anything falling into it gets stretched before it reaches the EH. – PM 2Ring Jun 08 '21 at 09:56

2 Answers

In order to survive, the star's self-gravitation must be larger than the tidal stretching forces provided by the black hole. If not, then the star will get spaghettified before it crosses the event horizon.

The tidal acceleration on a freely-falling star at the event horizon of a (non-spinning) supermassive black hole is approximately $$g_{\rm tidal}\simeq 2\frac{GM_{\rm BH}r_*}{r_s^3} = \frac{r_*c^6}{(2GM_{\rm BH})^2}\ , $$ where $M_{\rm BH}$ is the mass of the black hole and $r_*$ is the radius of the star. i.e. This is the difference in acceleration between the stellar surface closest to $r=0$ and that furthest away. (A more accurate treatment could integrate over the volume of the star).

Thus the tidal acceleration (i.e. tidal force per unit mass) becomes much smaller at the event horizon of larger black holes. If we demand that this tidal acceleration is less than the star's self-gravity, we can obtain a rough condition for survival. $$ \frac{r_*c^6}{(2GM_{\rm BH})^2} < \frac{GM_*}{r_*^2}$$ $$M_{\rm BH}> \left(\frac{c^6}{4G^3}\right)^{1/2} \left(\frac{r_*^3}{M_*}\right)^{1/2}\ .$$ In terms of solar masses and solar radii: $$ M_{\rm BH}> 1.6\times 10^8 \left(\frac{M_*}{M_\odot}\right)^{-1/2}\left(\frac{r_*}{R_\odot}\right)^{3/2}\ M_\odot\ .$$

Thus a star like the Sun might survive crossing the event horizon of a supermassive black hole of mass greater than 160 million solar masses.

Given that black holes more massive than this do exist at the centres of some active galaxies (for example, the $7\times 10^9 M_\odot$ black hole at the centre of M87), then this seems possible.

Of course, we cannot witness such an event because of gravitational time dilation.

NB: This answer assumes classical GR and in particular does not countenance the idea of a black hole firewall.

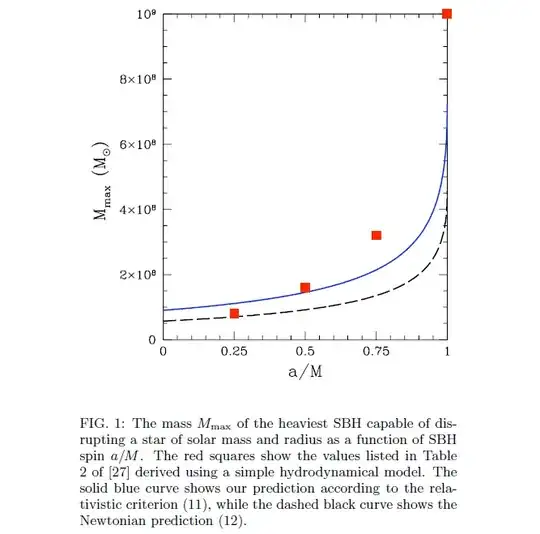

EDIT: The above is all back-of-the-envelope stuff. However, the basic number of 100 million solar masses being some sort of threshold agrees with popular accounts of the stellar spaghettification process. A more detailed theoretical treatment is provided by Kesden (2012), who also considers spinning black holes. The threshold black hole mass becomes larger for a spinning black hole - approximately $7\times 10^{8} M_\odot$ for a maximally spinning black hole - because the event horizon is at a smaller radial coordinate and the tidal forces are commensurately stronger. The picture below shows the dependence of the minimum mass to disrupt a solar-type star prior to crossing the event horizon as a function of the spin parameter of the black hole.

There is also some observational evidence that can be brought to bear on the matter. The spaghettification of a star (or tidal disruption event) can cause a lengthy transient brightening of an active galaxy. Some $\sim 50$ of these events have been obserevd (e.g. Gezari 2021). It turns out that there is indeed a fairly sharp cut-off in the black hole mass distribution for which these tidal disruption events have been seen. This cut-off occurs at $M_{\rm BH} \sim 10^8M_\odot$, suggesting indeed that more massive black holes are able to swallow stars whole.

- 151,483

- 9

- 359

- 566

-

1FWIW, https://www.vttoth.com/CMS/physics-notes/311-hawking-radiation-calculator says that the time to the singularity of a (Schwarzschild) BH of that mass is a little over 41 minutes. – PM 2Ring Jun 06 '21 at 19:20

-

1What about firewalls? What is the volume of a black hole? According to the logic of your answer, the volume of black hole must be greater than that of a star. Right? Obviously, your answer needs a completely classical supermassive black hole having a volume like that of a football ball in Euclidean space. Also, your black hole is far from realistic black holes. Your answer is based on some naïve, weak assumptions. – Ad Astra Jun 07 '21 at 12:59

-

@AdAstra the radius of the star is $\ll$ the Schwarzschild radius. Which formulation for black hole volume would make the black hole volume anything than $\gg$ the volume of the star (i.e. what is the ratio of the volume of the BH to the volume of the star, not the absolute volume of the BH)? Firewall? This is a novel (2012) hypothesis that requires abandonment of the equivalence principle. A contrasting answer providing the firewall argument would I'm sure be welcome. – ProfRob Jun 07 '21 at 13:11

-

@ProfRob Tidal acceleration can't be defined at a point. So tidal forces dont exist at the event horizon (of non-rotating black holes). – Deschele Schilder Jun 07 '21 at 13:34

-

1@Barberium Correct. A star isn't a point. That's why there is a $\simeq$ sign, because you have to average over the size of the object. Further reading: https://physics.stackexchange.com/questions/158144/event-horizon-of-supermassive-black-holes – ProfRob Jun 07 '21 at 13:56

-

1And note $r$ is not a radial distance (it is a spacelike radial coordinate) and it becomes a timelike coordinate inside the event horizon which makes the definition of black hole volume problematic (in the Schwarzschild coordinates that you assumed). – Ad Astra Jun 07 '21 at 15:51

-

3@AdAstra Where have I called $r$ a radial distance? Note that physical measurements (here, whether a star survives or not) do not depend on the adopted coordinate system. I'm fairly happy that this answer is correct for a non-spinning classical BH. – ProfRob Jun 07 '21 at 16:29

-

1I didn't say you mentioned that in your answer (If so, I would have mentioned it in my first comment.) That was a simplified reason for the problematic definition of black hole volume in its naïve geometric form (the right definition of black hole volume is controversial, still an open question). I thought you can draw the conclusion. And about this: "Note that physical measurements (here, whether a star survives or not) do not depend on the adopted coordinate system.", I'm not the guy who needs it ;) – Ad Astra Jun 07 '21 at 16:48

-

And remember that the answer to a hypothetical question is acceptable by specifying the theoretical framework of the answer and then by carefully determining the required assumptions but only those which are physically possible. Even within the context of GR, there are different notions for the black hole volume. This was my main point. Good luck. – Ad Astra Jun 07 '21 at 17:51

-

3@AdAstra it is not hypothetical. Black holes do swallow stars. I looked at a couple of theory papers and neither discuss the issue you think is important and the observational evidence concurs with a limit of around $10^8M_\odot$. The stars have such small masses and radii compared with $M_{\rm BH}$ and $r_s$ that they are treated as test particles. – ProfRob Jun 07 '21 at 19:47

-

I think Eq. (1) of the Kesden 2012 paper gives the answer to the OP question. Not sure you saw it before writing your equations, but I suspect you did not since your numerical prefactor is different, but the equations are the same. :) – Daddy Kropotkin Jun 07 '21 at 21:05

-

The question for the post author is completely a hypothetical question and he wants to know if this is physically possible or not. A qualitative answer was probably enough for him because it is clear that he does not have enough research on this (You cannot give him the fish.) You provided an answer with some details. This may sound convincing, but II argue does it have a solid theoretical framework? Your last edit is good but it wasn't necessary at all because the answer was clear from the beginning and was acceptable within certain assumptions which were added to the answer later. – Ad Astra Jun 07 '21 at 21:32

-

"Black holes do swallow stars." I think everybody in this field knows this fact! Even filmmakers like Claire Denis. And a quote from your answer: "Of course, we cannot witness such an event because of gravitational time dilation." Is this the way you want to have a scientific debate? Does entering the black hole without tidal disruption mean that the star stays healthy? How do you know that (and also the rest) when other parts of the puzzle are unknown? Yes, we can only rely on some scientific speculations which fit our observational data. That is just a suggestion. Hope you get my point now. – Ad Astra Jun 07 '21 at 21:46

-

What a great answer! Thinking about being eaten alive and not even knowing it, I've just asked Understanding various conditions where a star and a black hole meet and there is no tidal disruption; what all can we infer from this diagram? – uhoh Jun 08 '21 at 09:32

You can even consider our visible universe to be a black hole. As there are stars around us, they can live quite undisturbed in it. As seen from the part outside the horizon our region is the black hole. Stars from the other side seem to move onto our region but will be seen to end at the horizon (just as we see matter move onto their region, so seen from us it's their region that is a black hole). Then what's the singularity? It's a singularity at the the end of time.

The visible universe has a horizon too. An event horizon, because nothing further away than the horizon can affect us. This can be viewed as the event horizon of the black hole that we are in. There are no tidal effects killing us or the stars. For the stars, the event horizon is not important. And all of them find themselves inside a huge black hole (for which the density can be very small indeed!).

Note that the passage is one way. Once inside the region of the universe just over the horizon, matter can never can go back again.

The same holds for a star or, parts thereof, passing a large black hole. As soon as they have passed the horizon of the hole they are trapped. So if a star has enough velocity so it will not fully be pulled in, it will continue its travel with a lost part (which is, torn of from the star, left behind in the hole. If it is fully eaten then it will never reappear again. Initially, the star can stay as it is (low tidal force), but eventually, it will be torn apart and the particles constituting the star will end up at the singularity.

- 1

- 11

- 26

-

1The universe isn't a black hole. It's just that the observable universe's Schwarzschild radius is equal to its own radius (13.8 Gly) – WarpPrime Jun 07 '21 at 13:58

-

@fasterthanlight Doesn't make that the observable universe a BH? As seen from here all light seems to stop at the hole. So the universe outside is a black hole too. As seen from the outer universe our universe seems a BH too. It's just that it's that big that nothing in particular happens. – Deschele Schilder Jun 07 '21 at 14:06

-

4How does that answer the question? When did the Sun cross the event horizon of this black hole? – ProfRob Jun 07 '21 at 14:08

-

-

@Barbierium This is the difference between a black hole and an event horizon. You can define black holes in terms of event horizons without ever worrying about the physical singularity. For example, the big bang singularity has an event horizon but it is not a black hole solution to the Einstein Field Equations. – Daddy Kropotkin Jun 07 '21 at 15:06

-

1@DaddyKropotkin Can't the universe be seen as a white hole solution of the Einstein equations (in which case we are in the middle of a white hole, going backward in time, though for us it seems as if we are going backward)? – Deschele Schilder Jun 07 '21 at 15:31

-

I think so. This article is interesting. https://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/physics/Relativity/BlackHoles/universe.html – Daddy Kropotkin Jun 07 '21 at 15:43