A moon in an elliptical orbit may come into a tidal resonance with its planet instead of a full tidal lock. Or, a moon may not lock to its planet if it is in resonance with another moon. In addition tidal influences with the spin of the planet or with other moons in the system can cause a moon to be pushed out of the system, tidal acceleration, or pulled into the planet,tidal deceleration, before it ever has a chance to fully lock.

An alternative to tidal locking is orbital resonance, which occurs when celestial bodies exert periodic gravitational influence on each other, with their orbital periods related by a ratio of small integers. This phenomenon can be considered a form of tidal locking. A classic example of orbital resonance is seen in Jupiter's Galilean moons, where the orbital periods of Ganymede, Europa, and Io are in a stable 1:2:4 resonance configuration, effectively countering the planet-moon tidal effects. Callisto will someday also come into resonance.

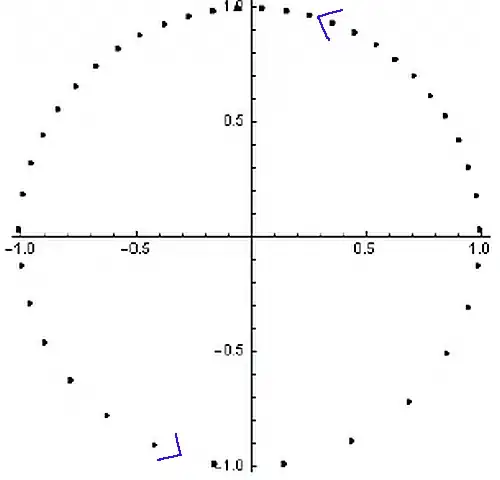

Another type of resonance is spin-orbit resonance, where the spin periods of moons are multiples of orbit period multiples.

Over extremely long timescales, on the order of hundreds of billions of years, the Sun's gravitational influence on Jupiter (raising a tidal bulge locked onto the Sun) will inevitably lead to energy dissipation through friction, gradually slowing down Jupiter's rotation until it becomes nearly locked to the Sun, completing one rotation in its solar year.

If a planet's spin were already tidally locked to the orbital period of a large moon, the interaction of the Sun's tidal forces and interacting of tidal bulges with winds in the atmosphere over an immensely long timescale would lead to the gradual removal of orbital energy from the moon's orbit. As a consequence, the moon's orbit would slowly decay (while spinning up the planet and maintaining the tidal lock), and it would eventually fall into the planet. It would then be free to start locking to its host star.

As for the moons of Jupiter, due to its rapid rotation, the gravitational drag from the bulges raised on Jupiter will cause the moons to slowly spiral outward, gradually increasing their orbital periods, likely maintaining their orbital period ratios as the periods lengthen. Eventually, they may escape the system altogether. If the moons have not been lost by the time Jupiter becomes nearly locked to the Sun, they will be pulled inward until they are either torn apart or burn up in Jupiter's atmosphere.

This generalizes to any planet with moons orbiting a star.

However, after ONLY 30 billion years or so, the entire solar system will probably have disintegrated from the disturbances of passing stars. See, “The Great Inequality and the Dynamical Disintegration of the Outer Solar System,” Jon K. Zink et al 2020 AJ 160 232.

On the longest time frame, gravity waves emitted by orbiting objects will remove their energy causing them to spiral in; moons into planets, planets into stars, stars into black holes at the center of galaxies, clusters and groups into their own centers.