In short: Both the pressure on the top side and on the bottom side push against the airfoil. The airfoil is overall pushed up, because the force on the bottom is larger than the force on the top.

Lift results from the pressure difference. Still we could say the top side (usually) participates more to the creation of this difference than the bottom side, in the sense the top side decreases the pressure below the ambient pressure more than the bottom side increases the pressure over the ambient pressure.

There is no "physical" lift force, lift and drag are engineering concepts. Lift is the vertical portion of the sum of all tiny pressures acting on the airfoil surface.

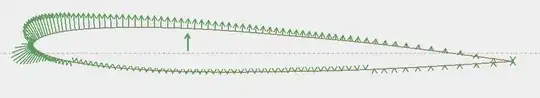

Conventional representation of the pressure variation created by airflow on an airfoil with positive lift:

Source.

Be aware of two confusing aspects in the picture:

There is no volumetric notion here , the lines indicate the pressure magnitude and direction directly at the airfoil surface. Pressure at any distance from the surface is unknown.

Arrows seem to indicate a suction effect on the top side, and a pushing effect on the bottom side. Remember pressure only pushes against the surface, it doesn't pull. Arrow indicate the sign of the pressure differential with atmospheric pressure, not the direction of the force. Arrows are exactly redundant with color here.

Red lines depict how much the pressure is in excess of the atmospheric pressure, blue lines depict how much the pressure is below atmospheric pressure. Pressure acts perpendicularly to the airfoil surface, hence the direction of the lines.

The bottom side sees a local pressure gradient which values are greater than atmospheric pressure, hence overall this side tends to push the wing up, more than atmospheric pressure alone.

The up side (unfortunately called the suction side in English) sees a local pressure gradient which values are lower than atmospheric pressure, hence overall this side tends to push the wing down, but less than atmospheric pressure alone.

Because the top pressure gradient is overall smaller than the bottom pressure gradient, the latter wins, the wing moves up. Whatever, all these pressures with disparate magnitudes and orientation don't combine in a perfect vertical force, the force is actually oblique. (And because the pressure differential at the leading edge is not the same than at the trailing edge, some positive or negative pitching moment is created too.)

Pressure force and aerodynamic force

To simplify, engineers mathematically integrate tiny pressures into a single symbolic larger force, the total aerodynamic force. For the airfoil above, the total force has an oblique orientation, up and back, hence the airfoil is pushed up and back.

Source.

Breakdown of the aerodynamic force into lift and drag

Engineers like to split this total force into a sum of two other symbolic forces of particular directions, drag and lift, to ease common computations. Note this decomposition is purely mathematical and has no actual physical interpretation.

The handy directions are the vertical and the direction of the flow. Lift, the vertical component, can be compared to weight to determine whether the aircraft will gain or lose altitude. Drag, the flow direction, can be compared with the propulsive force, to determine the velocity of the aircraft.

Varying the total aerodynamic force

The shape of the airfoil is the mean to change the magnitude and the orientation of these tiny forces, so every airfoil has a different distribution of the tiny pressures, and the distribution can change with the orientation of the airfoil:

Source.

Ultimately lift and drag conventional forces can be adjusted. With a negative angle of attack (top case), the aerodynamic force can be oriented down, lift has a negative magnitude.

From pressure to speed

Note how the pressure on the top side is mostly smaller than atmospheric pressure (- sign) and larger on the front part of the bottom side. Intuitively if you oppose a fluid (air or water) flow with your hand, or if your hand moves in a stationary fluid, you sense a force, fluid pressure has increased. The reason is because the flow has been slowed down. Conversely, if the flow is accelerated by some mean, pressure decreases (hand is not a good sensor for this negative pressure change).

Thus the sign of the pressure on the top side (also) indicates where the flow accelerates and where it slows down. Namely it always accelerates after some distance from the leading edge, even when the angle of attack is negative. This acceleration, combined with the deceleration on the bottom side results in a up force. Airfoil designers look for the "best" combination of changes to the flow speed at different angles of attack, e.g. one resulting in a near vertical sum.

Which side creates more pressure?

The total lift is the integral of all pressures, hence it corresponds to the difference between the sum of vertical components of all red and blue arrows of the first picture. Without performing the actual integration, it appears on the examples provided, the largest part of the lift comes from the top side, specially at high angle of attack. The stall angle is the limit, past the stall angle air acceleration starts to be problematic due to the apparition of vortexes. This is the direct answer to your question.