Gravity itself

@aeronalias is absolutely right.

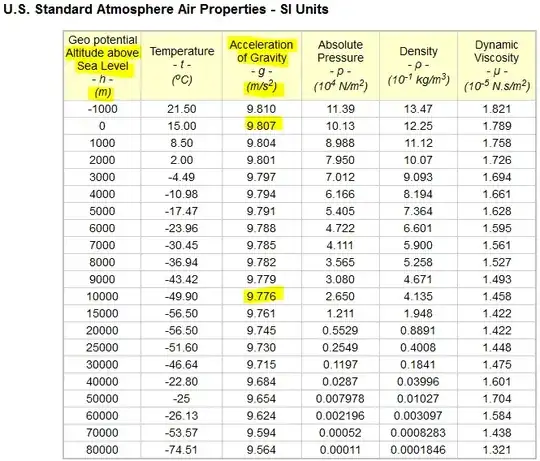

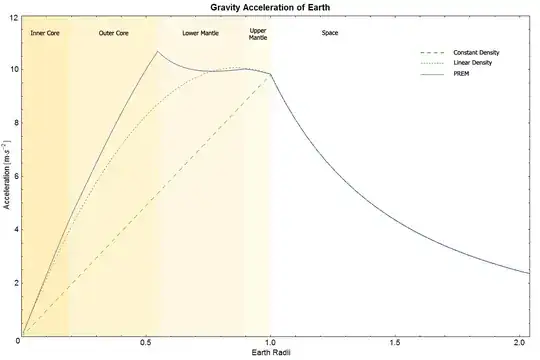

Given the gravitational acceleration of $g=9.81m/s^2$ on the ground, a perfect spherical earth of radius $R_E=6370km$ with homogenous (at least: radially symmetric) density, one can calculate the gravitational acceleration at an altitude of $h=12km$ by

$$g(h)=g\cdot\frac{R_E^2}{(h+R_E)^2}= 9.773 \rm{m}/s^2$$

Expressed in terms of $g$, the difference is

$$g_\rm{diff} = 0.0368565736 m/s^2 = 0.003757g$$

Centrifugal forces

The question also asks for the centrifugal effect on the aircraft as it travels round the curve of the earth, which has not yet been answered yet. The effect is considered small, but compared to the effect on gravity itself, it isn't always.

I got some heavy objections on my answer and I have to admit, I really don't see their point. Therefore, I've edited this section and hope this helps.

In general, an object moving on a circular path experiences a centrifugal acceleration, pointing away from the center of the circle:

$$a_c=\omega^2r=\frac{v^2}{r}$$

$\omega=\frac{\alpha}{t}$ is the angular speed, i.e. the angle $\alpha$ (in radians) the object travels in a given time $t$ (in seconds).

Now let's consider a "perfect" Earth as described above, plus no wind.

A balloon hovering stationary over a point at the equator at 12km altitude will do one revolution ($\alpha=2\pi[=360°]$) in 24 hours. So it is $\omega=\frac{2\pi}{24\cdot60\cdot60s}$. Together with $r=R_e+h$, one gets for the balloon:

$$a_{cb}=0.03374061 m/s² = 0.0034394098 g$$

The circumference of the circle the balloon flies is $2\pi(R_e+h)=40099km$

Now consider an aircraft flying east along the equator at the same altitude at 250m/s (900km/h, 485kt) with respect to the surrounding air. (Keep in mind: no wind). In 24h, this aircraft travels a distance of 21600km, or 0.539 of the circumference. This means the aircraft does 1.539 revolutions of the circle in 24h, which means its angular speed is $\omega=1.539\cdot\frac{2\pi}{24\cdot60\cdot60s}$.

Thus, the centrifugal force on the aircraft flying east is

$$a_\rm{ce} = 0.0799053814 m/s^2 = 0.0081452988 g$$

The same way, one can calculate what happens when the aircraft flies west:

$\omega=(1-0.539)\cdot\frac{2\pi}{24\cdot60\cdot60s}$

$$a_\rm{cw} = 0.0071833292 m/s^2 = 0.0007322456 g$$

Comparison

Let's write the values together to compare them. I've also added how much lighter a 100kg (220lb) person would feel due to the effects:

| "weight loss"

g_diff = 0.0368565736 m/s² = 0.003757 g | 376gram (0.829lb)

a_cb = 0.03374061 m/s² = 0.0034394098 g | 344gram (0.758lb)

a_ce = 0.0799053814 m/s² = 0.0081452988 g | 815gram (1.797lb)

a_cw = 0.0071833292 m/s² = 0.0007322456 g | 73gram (0.161lb)

Note: The 100kg is what a scale at the North Pole (i.e. without any centrifugal effect) shows. The person already feels 344g lighter on the ground at the equator. The balloon doesn't change this (much).

But moving east/west has a larger effect on the weight than gravity alone. A person flying west feels even heavier than on ground!

Maybe another table, showing the weight of the person:

kg lb

1. Man at north pole 100.00 220.46

2. Man at equator 99.66 219.70

3. Man at equator, in balloon 99.28 218.88

4. Man at equator, in aircraft flying east 98.81 217.84

5. Man at equator, in aircraft flying west 99.55 219.47 <- More than 3.

The numbers shown are only valid at the equator and for flights east / west. In other cases, it becomes a little more complex.

EDIT: Being curious on how this depends on latitude, I created this plot about the absolute acceleration an aircraft experiences.

The radius in the equation of the centrifugal force is the distance of the aircraft to the axis of the Earth. It is clear that it decreases when moving away from the equator, and so does the acceleration.

The speed of the aircraft flying west will cancel out the speed of the earth at about 57° N / S, i.e. there is no centrifugal force. At larger latitude, the aircraft will fly in the opposite direction around the axis of the earth, building up a centrifugal force again.

Near the poles, both aircraft become centrifuges (theoretically). E.g. flying a circle of 500m radius gives an acceleration of 12.7g. This is why the data rises to infinity there.

(When doing the math, one has to keep in mind that gravity always points to the center of the earth, while the centrifugal force points away from the axis. You can't just add them)