You ask why doesn't it go all the way up... but all the way up to where? It's somewhat of an arbitrary limit, but FL600 tends to generally be the top of the troposphere, so it seems like a good choice if we're picking numbers.

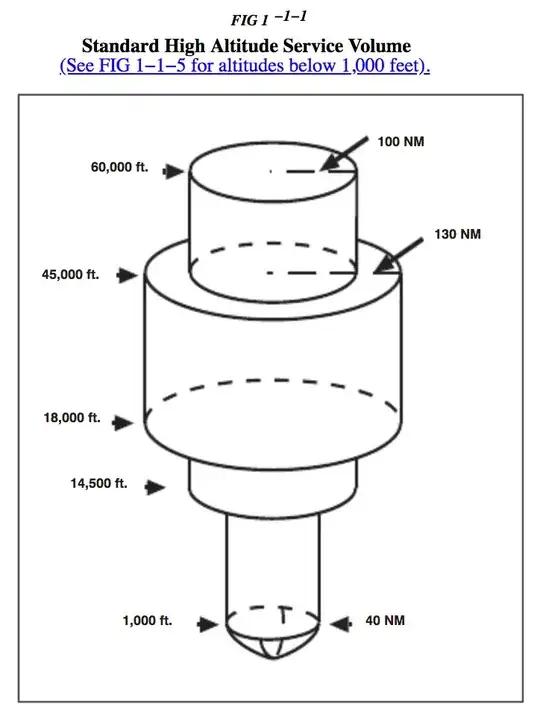

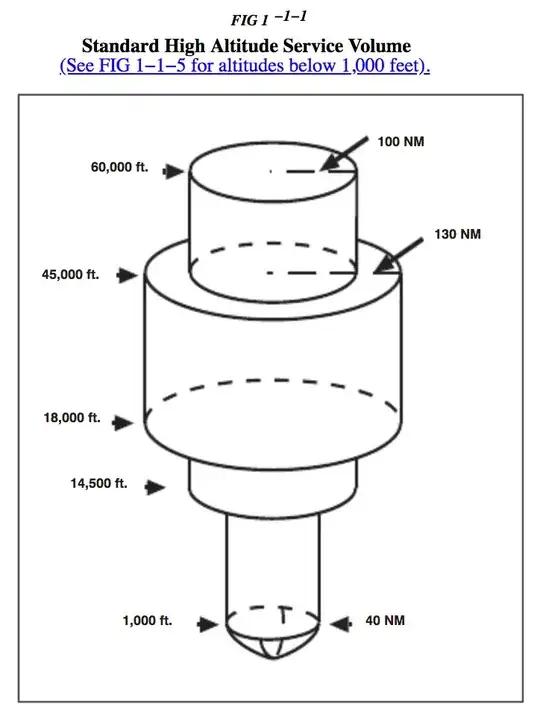

One reason could be that the FAA AIM (Airman’s Information

Manual) says that the top of the service volume for the high-altitude

VORs is 60,000 feet above the VOR facility, so it seemed like a good altitude to end the restriction of Class A, that all aircraft must be on an IFR flight plan. If you're tooling around above FL600, perhaps you don't want/need to be on an IFR flight plan (think experimental planes, rocket launches, etc.)

It could also be that when they set up the airspace, there wasn't a whole lot going on above 60,000 feet, and given that survivability at that altitude without a space suit is low, so there weren't a lot of aircraft that high, plus the top of the troposphere is around that altitude, it just seemed to be a good number. Most commercial aircraft have a service ceiling well below FL600 (the Boeing 777 ceiling is FL431), and since Class A is positively controlled airspace with everyone having to be on an IFR flight plan, aircraft above FL600 are not as common, and so it didn't make sense to spend resources (at the time) to force things that high to go through some kind of waiver process, or put the effort in maintaining the services required to provide IFR separation services for aircraft that high.

However, as we look to the future, there is a great report from Embry-Riddle about Safe Operations Above FL600 that sheds some light on what goes on above FL600 and considerations that should be taken into account going forward as the airspace starts to get more crowded with drones, and planned spaceflight and supersonic transports.