Here's one way-- not the only way-- to look at the dynamics involved--

Imagine an aircraft in a 45-degree-banked constant-altitude turn. Now imagine that the pilot gradually adds more and more power and the aircraft gradually enters a steeper and steeper climb until it is climbing almost straight up. Can you see how to maintain a constant bank angle, the aircraft must actually roll toward the high wingtip? As the climb angle gets steeper, the maneuver gets closer and closer to resembling a vertical rolling climb, with the direction of roll being toward the wingtip that was originally the high wingtip in the constant-altitude turn.

"Fly" through the maneuver with your hand or with a little hand-held model airplane until you understand this.

(Like this-- https://vimeo.com/128025851#t=157s -- video intentionally starts at 2:37)

Now, can you see how a rolling motion always tends to increase the angle-of-attack of the descending wingtip, and to decrease the angle-of-attack of the rising wingtip? As the descending wingtip comes down through the airmass, the local relative wind blows "up from below" compared to the local relative wind closer to the aircraft centerline-- this is an increase in angle-of-attack. Similarly, as the rising wingtip moves up through the airmass, the local relative wind blows "down from above", or at least blows up from below at a shallower angle than the local relative wind closer to the aircraft centerline. This is a decrease in angle-of-attack. These changes in angle-of-attack create an effect known as "roll damping"-- a resistance to rolling. This is why the roll rate doesn't just keep getting faster and faster as long as we hold the ailerons in a deflected position.

So that's the answer to your question. In a constant-banked climbing turn, the aircraft is continually rolling toward the high wingtip, so the high wingtip experiences an increase in angle-of-attack and the low wingtip experiences a decrease in angle-of-attack.

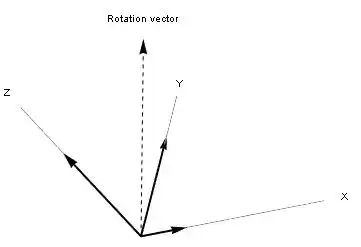

Note that while our thought experiment involved a continual increase in climb angle and climb rate, the basic dynamics we're talking about are present even in a climb at constant angle and rate. In a climbing turn, an aircraft must continually roll toward the high wingtip to hold the bank angle constant. Otherwise the bank angle will increase. It's not a matter of aerodynamics, but rather of three-dimensional geometry.

In a descending turn, everything is the same except that to keep the bank angle constant, the direction of roll must be toward the LOW wingtip, so the low wingtip experiences an increase in angle-of-attack and the high wingtip experiences a decrease in angle-of-attack.

"Fly" through the descending turn case with your hand or a little hand-held model airplane until you understand that the extreme case of a constant-bank descending turn is a vertical rolling spiral, with the direction of roll being toward the wingtip that was originally the low wingtip when the plane was turning with a constant altitude or with a less-than-vertical dive angle.

(Like this-- https://vimeo.com/128025851#t=128s -- video intentionally starts at 2:08)

As a footnote, you can see how aerodynamic "damping" in roll -- the tendency for the roll rate to decrease-- exerts a destabilizing influence in a climbing turn, tending to make the bank angle increase. In a descending turn, aerodynamic "damping" in roll tends to make the bank angle decrease. This is very noticeable in some applications, such as powered hang gliders and trikes.

As another footnote, understand that we are speaking of "ascending" and "descending" relative to the surrounding airmass-- an unpowered glider spiralling up in a thermal updraft is still in a "descending" turn for the purposes of this discussion.

As yet another footnote, we can observe that it is easy to see how the bank angle can change when we pitch up with zero roll rate, in some version of a chandelle or wingover for example. It is harder to see how bank angle can be constant and roll rate can be non-zero in a climbing or diving turn, but it's true, as illustrated in the video links given above. Again, it's fundamentally a matter of 3-dimensional geometry, not aerodynamics.

In closing, here is a link to a diagram from John S. Dencker's "See How it Flies Website" that illustrates how a rolling motion creates a difference in angle-of-attack between the two wingtips. The diagram is not dealing specifically with the constant-bank case, and also it is really aimed at explaining "adverse yaw" which is a separate issue, but it still may be helpful-- https://www.av8n.com/how/htm/yaw.html#sec-adverse-yaw