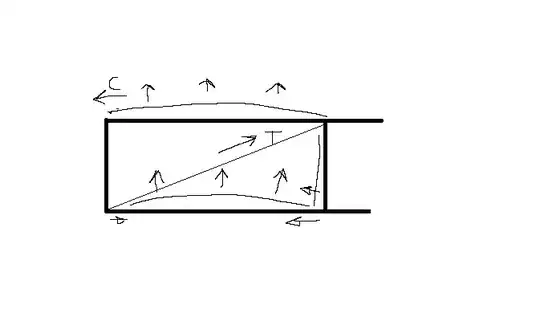

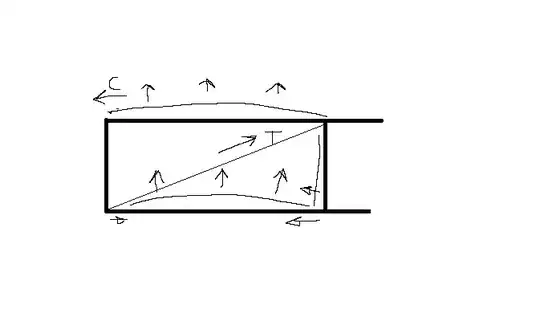

It's not a tension member in that sense. This is a pin jointed truss with flexible tenion-only diagonals. The lower wing is a non-cantilevered beam, that is, supported at both ends, so it will bow up in the center under load with flight loads, and this applies a modest tension load at the root (as well as pulling the bottom of the interplane strut inboard, to the extent that deformation occurs in the main spar beam). If the lower wing's spar had perfect rigidity and didn't bend at all, there would be no tension load at all at the wing root; it would be all vertical shear.

If you thought of the lower wing as a sheet of fabric, and imagine that the interplane strut at the outer end was rigid vertically, you'd have basically an upside down hammock, and when you lay in a hammock, the attachments are under tension (of course, the outer interplane struct not being rigid vertically, the hammock would collapse straight up - in the biplane's case the lower "hammock" is a semi-rigid length of lumber that only deflects slightly so the outer interplane strut doesn't have to be vertically fixed). So the extent of any tension load at the root fitting for the lower wing, it's only to the extent that there is a hammock effect happening as the spar deforms.

To get the lower wing to work in tension as part of rigid truss system with the upper and lower wings integrated into it, the X of diagonal wires have to be replaced with rigid struts that can take compression. The rigid strut running down from the upper root to lower tip would be in compression, sharing load with the other one in tension, and this would make the lower wing a tension member in the system. But with tension-only flying wires, that doesn't happen.

Clear as mud?