- Short Answer: This is a result of making the aircraft stable in longitudinal axis.

Longitudinal Stability Basics

Nomenclature: $C_m$ is the pitching moment coefficient. Pitch-up moment is denoted by +ve $C_m$. Also, $α$ denotes Angle of Attack.

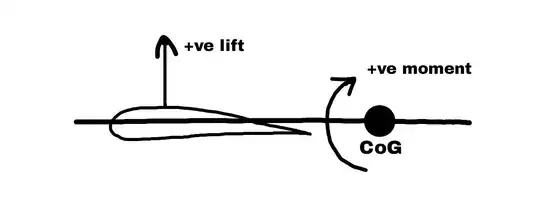

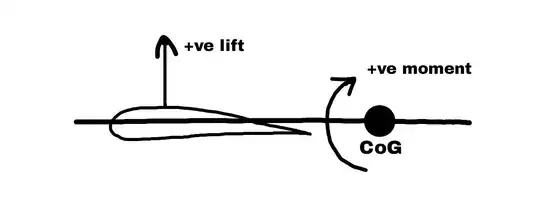

If the AC of a surface is ahead of CG, then that surface has a destabilizing contribution. This can be understood through this image:

A positive $∆α$ will produce a positive $∆C_m$ (pitch-up). This becomes a vicious cycle, since pitching-up will further increase the $α$ - that in turn will increase the $C_m$ further (greater pitch-up moment) and so on. Basically, the aerofoil will have a tendency to diverge away from equilibrium - on its own, it is statically unstable.

Likewise, if AC is behind CG, a positive $∆α$ produces a negative $∆C_m$ (pitch-down). Pitching down will reduce the $α$ - the aerofoil has a tendency to return back to its trim $α$ and is thus statically stable.

Making a stable aircraft

A conventional aircraft primarily has two surfaces that determine its longitudinal stability - the wing and the tail.²

Wing: Its contribution can either be stabilizing or destabilizing, depending on the position of CG relative to its AC.

Tail: Its contribution is always stabilizing, since CG is always ahead of tail AC.

Consider an aircraft with its wing AC ahead of aircraft CG. In that case, the wing has a destabilizing contribution.

Wing contribution: (destabilizing) $$\frac{dC_{m\ wing}}{dα} > 0$$

Tail contribution: (always stabilizing) $$\frac{dC_{m\ tail}}{dα} < 0$$

It is desirable to have a wing on an aeroplane, but a conventional wing on its own is unstable. To fix this, we add a tail.

Now, how do we ensure that the tail would be enough? It is necessary to ensure that the stabilizing contribution of tail is greater than the destabilizing contribution of wing:

$$ \left( \frac{dC_{m\ wing} + dC_{m\ tail}}{dα} \right) < 0 $$

This ensures that the aircraft as a whole is statically stable. But how is this achieved in practice? - By putting the CG ahead of the neutral point

CG position

Neutral point: This is the point on the longitudinal axis at which positioning the CG results in the aircraft having no tendency:

If an aircraft with neutral stability is subjected to a disturbance that changes its $α$, then that will produce zero net $C_m$. This means that the aircraft will find itself in a new equilibrium, and will now maintain this new $α$.

At neutral point, wing's destabilizing moment is equal in magnitude to tail's stabilizing moment - that's why their combination is neutral.

If CG is moved ahead of the neutral point, the aircraft becomes stable. This is because:

Tail moment arm increases: This increases its stabilizing effect.

Wing moment arm reduces: In our example where wing AC is ahead of CG, wing arm reduces. This reduces its destabilizing effect.

Likewise, if CG is moved aft of the neutral point, the aircraft becomes unstable. This is because wing's unstable contribution increases and tail's stable contribution decreases.

Till now, we have considered an example where wing AC is ahead of CG. In practice, the stability required is usually so large that it can only be achieved by moving CG well ahead of wing AC. This is the configuration we see in most conventional aircraft.

Trimming the moments

With the aircraft in equilibrium at the neutral point:

the positive $C_{m\ wing}$ will be equal in magnitude to the negative $C_{m\ tail}$.

Also, a change in $α$ will produce proportional change in the $C_{m}$ of both the wing and the tail, such that no net change in pitching moment is produced.

Moving CG ahead of the NP reduces +ve wing moment and increases -ve tail moment. The combined result is a net -ve $C_{m}$. To trim that out, tail incidence must be reduced. This produces what is known as "longitudinal dihedral" or "decalage" or whatever you wish to call it.

Dihedral: Angle between two planes.

Longitudinal dihedral: Angle between wing and tail. More specifically, the difference between wing incidence and tail incidence. A positive LD is where wing incidence is greater than tail incidence.

For a longitudinally stable aircraft, trim will be obtained when the wing incidence is greater than tail incidence (positive dihedral). For an unstable aircraft, it's the opposite - wing incidence will be less than tail incidence at equilibrium (negative dihedral). For a neutral aircraft at equilibrium, wing incidence will equal tail incidence (no dihedral).¹

Finally, answer to the question:

As stated earlier, the amount of stability that most conventional aircraft require can only be produced by moving the CG well ahead of wing AC. However, this causes the wing to produce a negative $C_m$.

To trim this out, the tail has to produce a positive $C_m$, and to do that, it needs to produce a downforce. And it needs a negative incidence to produce that downforce.

Again, this dihedral (difference in incidence) is formed as a result of making the aircraft statically stable in pitch. That answer you linked to is referring to the fact that if the aircraft is stable, it will (generally) have this LD.

Note that simply creating a large longitudinal dihedral (giving the tail a negative incidence) won't produce stability, it's the other way around. Making a stable aircraft by moving the CG forward (and then trimming it) will produce a longitudinal dihedral as a byproduct.

¹ For simplicity, this entire paragraph ignores the fact that wing modifies the flow at tail (by inducing a downwash and reducing the dynamic pressure). In practice, the only thing guranteed for a stable aircraft in equilibrium is that lift-per-unit-area at wing will always be greater than that at the tail, which generally translates to wing incidence being greater than tail incidence.

² For simplicity, this answer only considers the contributions of wing and tail. Surfaces like fuselage and engine-nacelles etc. will have their own contribution (usually destabilizing).