edit: Results are current as of Dec 4, 2018 13:00 PST.

Background

K-mers have many uses in bioinformatics, and for this reason it would be useful to know the most RAM-efficient and fastest way to work with them programmatically. There have been questions covering what canonical k-mers are, how much RAM k-mer storage theoretically takes, but we have not yet looked at the best data structure to store and access k-mers and associated values with.

Question

What data structure in C++ simultaneously allows the most compact k-mer storage, a property, and the fastest lookup time? For this question I choose C++ for speed, ease-of-implementation, and access to lower-level language features if desired. Answers in other languages are acceptable, too.

Setup

- For benchmarking:

- I propose to use a standard

fastafile for everyone to use. This program,generate-fasta.cpp, generates two million sequences ranging in length between 29 and 300, with a peak of sequences around length 60. - Let's use

k=29for the analysis, but ignore implementations that require knowledge of the k-mer size before implementation. Doing so will make the resulting data structure more amenable to downstream users who may need other sizesk. - Let's just store the most recent read that the k-mer appeared in as the property to retrieve during k-mer lookup. In most applications it is important to attach some value to each k-mer such as a taxon, its count in a dataset, et cetera.

- If possible, use the string parser in the code below for consistency between answers.

- The algorithm should use canonical k-mers. That is, a k-mer and its reverse complement are considered to be the same k-mer.

- I propose to use a standard

Here is generate-fasta.cpp. I used the command g++ generate_fasta.cpp -o generate_fasta to compile and the command ./generate_fasta > my.fasta to run it:

return 0;

//generate a fasta file to count k-mers

#include <iostream>

#include <random>

char gen_base(int q){

if (q <= 30){

return 'A';

} else if ((q > 30) && (q <=60) ){

return 'T';

} else if ((q > 60) && (q <=80) ){

return 'C';

} else if (q > 80){

return 'G';

}

return 'N';

}

int main() {

unsigned seed = 1;

std::default_random_engine generator (seed);

std::poisson_distribution<int> poisson (59);

std::geometric_distribution<int> geo (0.05);

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> uniform (1,100);

int printval;

int i=0;

while(i<2000000){

if (i % 2 == 0){

printval = poisson(generator);

} else {

printval = geo(generator) + 29;

}

if (printval >= 29){

std::cout << '>' << i << '\n';

//std::cout << printval << '\n';

for (int j = 0; j < printval; j++){

std::cout << gen_base(uniform(generator));

}

std::cout << '\n';

i++;

}

}

return 0;

}

Example

One naive implementation is to add both the observed k-mer and its reverse complement as separate k-mers. This is obviously not space efficient but should have fast lookup. This file is called make_struct_lookup.cpp. I used the following command to compile on my Apple laptop (OS X): clang++ -std=c++11 -stdlib=libc++ -Wno-c++98-compat make_struct_lookup.cpp -o msl.

#include <fstream>

#include <string>

#include <map>

#include <iostream>

#include <chrono>

//build the structure. measure how much RAM it consumes.

//then measure how long it takes to lookup in the data structure

#define k 29

std::string rc(std::string seq){

std::string rc;

for (int i = seq.length()-1; i>=0; i--){

if (seq[i] == 'A'){

rc.push_back('T');

} else if (seq[i] == 'C'){

rc.push_back('G');

} else if (seq[i] == 'G'){

rc.push_back('C');

} else if (seq[i] == 'T'){

rc.push_back('A');

}

}

return rc;

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[]){

using namespace std::chrono;

//initialize the data structure

std::string thisline;

std::map<std::string, int> kmer_map;

std::string header;

std::string seq;

//open the fasta file

std::ifstream inFile;

inFile.open(argv[1]);

//construct the kmer-lookup structure

int i = 0;

high_resolution_clock::time_point t1 = high_resolution_clock::now();

while (getline(inFile,thisline)){

if (thisline[0] == '>'){

header = thisline.substr(1,thisline.size());

//std::cout << header << '\n';

} else {

seq = thisline;

//now add the kmers

for (int j=0; j< thisline.size() - k + 1; j++){

kmer_map[seq.substr(j,j+k)] = stoi(header);

kmer_map[rc(seq.substr(j,j+k))] = stoi(header);

}

i++;

}

}

std::cout << " -finished " << i << " seqs.\n";

inFile.close();

high_resolution_clock::time_point t2 = high_resolution_clock::now();

duration<double> time_span = duration_cast<duration<double>>(t2 - t1);

std::cout << time_span.count() << " seconds to load the array." << '\n';

//now lookup the kmers

inFile.open(argv[1]);

t1 = high_resolution_clock::now();

int lookup;

while (getline(inFile,thisline)){

if (thisline[0] != '>'){

seq = thisline;

//now lookup the kmers

for (int j=0; j< thisline.size() - k + 1; j++){

lookup = kmer_map[seq.substr(j,j+k)];

}

}

}

std::cout << " - looked at " << i << " seqs.\n";

inFile.close();

t2 = high_resolution_clock::now();

time_span = duration_cast<duration<double>>(t2 - t1);

std::cout << time_span.count() << " seconds to lookup the kmers." << '\n';

}

Example output

I ran the above program with the following command to log peak RAM usage. The amount of time the lookup of all k-mers in two million sequences is reported by the program. /usr/bin/time -l ./msl my.fasta.

The output was:

-finished 2000000 seqs.

562.864 seconds to load the array.

- looked at 2000000 seqs.

368.734 seconds to lookup the k-mers.

1046.94 real 942.38 user 78.96 sys

11680514048 maximum resident set size

So, the program used 11680514048 bytes = 11.68GB of RAM and it took 368.734 seconds to lookup the k-mers in two million fasta files.

Results

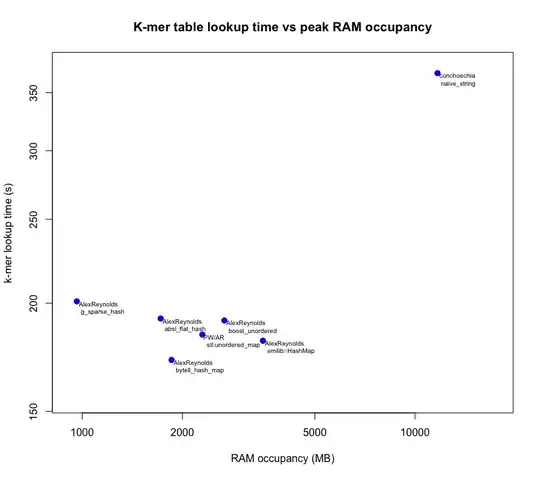

Below is a plot of the results from each user's answers.

std::unordered_mapinstead ofstd::mapas a simple improvement (hopefully) – Peter Menzel Nov 04 '18 at 09:50generate-fasta.cppdoes not compile. I also don’t understand its logic; why the multiple random distributions? What are you modelling? Thegen_basefunction confuses me. – Konrad Rudolph Nov 20 '18 at 12:57gen_basefunction uses a random int between 1-100 as input to select a base. The ranges in the function give it some AT bias, The Poisson distribution makes a bunch of sequences around 59 bp long, but the geometric distribution gives it a long tail of sequence lengths. In this case I was modeling a distribution of some sequences I need to look up kmers for. – conchoecia Nov 21 '18 at 00:47