I can understand why some prey can't outrun a recently evolved species. However, since cheetahs have existed for so long, why haven't its prey evolved to always outrun it, driving cheetahs to extinction. Is it because the cheetah population size is so much smaller than the population size of most of its prey species that its prey species are under very weak natural selection to outrun cheetahs? Is it that those that can run faster have more other biological costly traits?

-

63what will stop predators to evolve to always catch their prey? – aaaaa says reinstate Monica Apr 19 '16 at 03:47

-

There are limits to how fast a given animal can go. Prey also tend not to run in straight lines so there are many ways to improve via evolution.... there are no supersonic animals for instance! – shigeta Apr 19 '16 at 03:51

-

2For further reading check out the Red Queen Hypothesis – Luigi Apr 19 '16 at 04:21

-

11An alternative (facetious) question: "Why haven't they evolved wings to just fly away?" I've marked this question as a duplicate of "If a trait would be advantageous to an organism then why hasn't it evolved yet?" – James Apr 19 '16 at 06:33

-

What prevents predator overpopulation? explains the dynamic between preys and predators in absence of evolution. That may interest you. – Remi.b Apr 19 '16 at 06:46

-

24Just remember, not all prey are at their peak physical fitness all the time. Just because a cheetah caught one one doesn't mean it could have caught any. In other words, perhaps all prey actually can out run a cheetah, but not when they: are sick, pregnant, juvenile, in the middle of taking a dump, half asleep, critically dehydrated, in unfamiliar territory etc... What I'm getting at is that your assumption that "caught and eaten" = "can't out run a cheetah" is not necessarily accurate – Bamboo Apr 19 '16 at 07:18

-

10The same way, if prey "evolved" to always outrun their predators... the predators would simply start attacking their young, who can't outrun them yet. Which actually happens all the time, so prey animals "learned" to protect their young (e.g. herding). Running faster doesn't help you protect your children - and prey animals who run away while letting their children get eaten don't pass their traits on future generations. – Luaan Apr 19 '16 at 08:12

-

29They don't have to outrun their predators, they just have to outrun their friends! – Sobrique Apr 19 '16 at 13:43

-

1@James Before I read your comment I was going to reply with "Of course they've evolved, we have birds don't we?", in jest of course :) – MonkeyZeus Apr 19 '16 at 19:11

-

If prey were never caught by their predators then they would not have predators. The question is essentially meaningless if taken literally (e.g. "always"). – Drew Apr 19 '16 at 20:19

-

predators cull the week from the herd, allowing the strong increased access to food and mates. while unfortunate for the eaten animal, it is beneficial to the long term success of the species. and that is all your genes care about. – teldon james turner Apr 20 '16 at 00:30

-

I have decided not to vote to close: much of the material is covered in the duplicate but this question also relies heavily on co-evolutionary arms races which is not covered in the other question. – rg255 Apr 20 '16 at 05:19

-

"Evolution is a journey, not a destination." In other words, they're working on it; give them time. (Meanwhile, they're hoping cheetah's don't evolve jetpacks. Although I'm not, because cheetahs with jetpacks are cool.) – Eric Towers Apr 20 '16 at 05:27

-

2can't believe this question got 6 answers. People need hobbies – aaaaa says reinstate Monica Apr 20 '16 at 05:29

-

2@aaaaaa Or some predators chasing them away from their computers. – Count Iblis Apr 20 '16 at 23:25

-

The main thing to get is that there is no end game for evolution. (and that its not a competition) Its an ongoing process of species adapting to changing circumstances. – JamesRyan Apr 21 '16 at 10:32

-

Maybe the preadator prey system is an evolutionary stable strategy. There's a biological cost for the prey running away faster because doing so burns more energy and it's not definite that it will get eaten if it doesn't. If the preadator population size is larger, the prey evolve to run away faster because they need less risk of being eaten on each chase in order to survive and reproduce and that reduces the preadator population size. – Timothy May 18 '16 at 01:45

-

I think this might actually be an unsolved problem. None of the answers fully explain why they don't always outrun their predators. Ell's answer doesn't explain why the cheetah and gazelle system appears to be stable without gazelles evolving to be even faster at running away. Surely some people are so smart that they could actually figure out the answer to this question. – Timothy Jan 17 '17 at 04:11

3 Answers

There are (at least) three important factors to consider here; evolution under selection requires genetic variation upon which to act, selection can act on covarying traits causing trade-offs, and adaptation also occurs in the predator. A lot of this is covered elsewhere on this site (including the effects of the other mechanisms of evolution), but little specific reference is made to predator-prey co-evolution.

Adaptation and genetic variance

One of the mechanisms of evolution is selection, and adaptation occurs when species evolve as a response to selection. For a response to selection to occur there must be genetic variation within the trait, such that the genes an individual carries affect the individuals fitness. For example, there may some genes which give the carrier better muscle structure for fast running, and this increases survival which, in turn, increases reproductive output. The importance of genetic variation is often overlooked, but is highlighted by the breeders equation. Genetic variance can arise by novel mutations, or can exist as standing genetic variance.

Selection on covarying traits

Selection is seldom, if ever, a univariate process. That means fitness is not determined by a single characteristic, so fitness in a prey species may be determined by the speed at which it can run, but also its metabolic rate, stamina, ability to acquire nutrients, the way it provisions nutrients for growth and repair etc.. Genetic covariance between traits (induced by linkage or pleiotropy) can impact the response to selection, because any selection acting on a covarying trait can cause affect the adaptation occurring in the focal trait (strengthening, weakening, neutralising, or even reversing the direction of response). Therefore, if running speed covaries with other traits it may be difficult for selection to increase running speed. Think about athletes, I doubt Usain Bolt could run 10,000 metres as fast as Mo Farah and vice versa, because there is a trade-off between speed and stamina.

Adaptation in other species

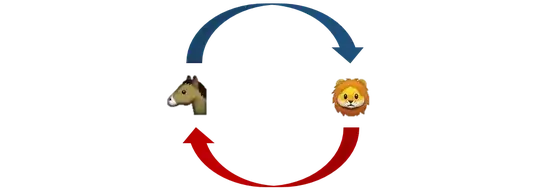

If selection did cause speed to increase in the prey species then that would strengthen selection for increased speed in the predator. This is called an evolutionary arms race, where the adaptive the evolution of two species interacts causing adaptation and counter-adaptation. For example, genes which allow faster running might spread through a population of gazelles (prey) because carriers are more likely to outrun the lion (or the other gazelles), but this will increase selection on lions (predator) to increase speed (or adopt other strategies) which will spread genes to make the lions faster (use other strategies); the result being adaptation and counter-adaptation between the gazelle and lion populations.

There is a little series here about Butch Brodie and his studies of coevolutionary arms races between garter snakes and toxic newts. It would be good to read on the Red Queen Hypothesis, which describes how species, under interaction with other species, must continue to evolve just to prevent extinction. Also worth noting that prey species often have more than one predator species (and predator species often have more than one prey); interaction and coevolutionary networks are complex. What may be adaptive in some interactions may also be maladaptive for other interactions (see specialist and generalist, and selection on covarying traits).

-

1Good answer, but for readability I would restructure it and put the arms race/RQH parts at the top, since those issues are most targetted to this particular question. Genetic variation and covariation/trade offs are always an issue in evolution, but more general than the coevolution between predators and prey. – fileunderwater Apr 19 '16 at 11:04

-

Maybe it would. I put it this way around to introduce the concept of adaptation as a response to selection first before talking about how subsequent adaptation can affect selection in other species. I also put the comment at the start regarding predator-prey co-evolution to highlight it's importance from the outset. – rg255 Apr 19 '16 at 12:18

-

Assuming the animal books I read as a child didn’t lie to me, the peregrine falcon and pigeon might be a rather insightful example of an arms race, since (the book asserted) the two birds’ body shapes are similar because the shape is well-adapted to high speed, and the peregrine falcon is so fast because of its constant need to maintain a speed advantage over pigeons. (That factoid really captured my interest and has stuck with me, so here I am rather confident that if incorrect, it is the book’s fault and not my memory’s. :P) – KRyan Apr 19 '16 at 14:10

-

4When looking at what's evolutionarily favorable, you need to keep in mind that predator-prey relationships are rarely a simple binary. For example, evolving speed to out-sprint the lion won't help if you're being chased by a human who will keep pursuing until you drop from exhaustion. – Mark Apr 19 '16 at 22:29

-

The snake / newt arms race was the first thing I thought of when I read the question. – TecBrat Apr 20 '16 at 00:55

-

I don't understand why it seems like the cheetah and gazelle system is stable and gazelles aren't evolving to run away even faster. Do you know a more detailed answer of the different reasons a prey species gets eaten by predators as often as it does? If so, can you edit your answer to explain it? – Timothy Jan 17 '17 at 04:18

There are two reasons for this: evolutionary trade-offs and coevolution (the "Red Queen hypothesis", as mentioned in the comment above by Luigi).

Evolutionary trade-off describes situations where one trait cannot increase without a decrease in one or more others. Some hypothetical examples:

- longer legs may help run faster, but past a certain point, it will increase the risk of injury, decreasing survival;

- lower body weight may increase top speed, but past a certain point, it will decrease starvation tolerance;

- more muscle may help acceleration but will increase energy requirements.

All changes have costs and benefits. In situations where the outcome of an event is simply "success/failure", there is therefore an evolutionary incentive to evolve to be just good enough. Once you are good enough getting better only increases the cost (I am oversimplifying this a bit).

Change in an extrinsic driver will change the balance of cost and benefit, shifting evolutionary pressure. For example, when predators are absent (island populations) birds sometimes become flightless, because one benefit of flight (escape from predators) no longer applies.

The interesting bit happens when the "extrinsic driver" is another living thing that is also capable of evolving. In this case you suddenly get an evolutionary arms race where each side is constantly subject to a selective pressure to be slightly better than the other, which is a moving target. You therefore get an arms race situation (or the extinction of one or the other side). The Red Queen hypothesis is named after a quote by the Red Queen in "Alice through the looking glass" (Carroll, 1871):

Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.

Using the example of a lion and a gazelle: lions run fast enough to catch and eat the slowest gazelles. The remaining gazelles are on average faster, for whatever reason(s). Some of those reasons will be heritable and the next generation of gazelles will be faster. The slowest lions will starve, and some of the reasons for the remaining lions being faster will be heritable so the next generation will be a bit faster, and then you're back where you started. Rinse and repeat.

Predation obviously operates on a much faster timescale than selection, so this doesn't always occur (putting a fox in a chicken coop won't evolve fast chickens).

Coevolutionary "arms races" can be seen in predator-prey interactions, mimicry and much more (including for example the evolution of sex, but that's off-topic for this answer).

-

I would use the leopard as an example which actually is fully in this arms race. – Thijser Apr 19 '16 at 09:53

-

1To what extend would e.g. a 5% increase in the speed of all the gazelles in an area affect predation? I would think that in many cases, the primary limiting factor on the speed of animals caught by lions is the speed of the slowest prey animal. Once the lion has caught the slowest animal, the remaining animals will be safe from that lion for awhile. Unless a species gets fast enough to outrun some other prey species, it's unlikely to get fast enough for all its members to outrun predators. – supercat Apr 19 '16 at 16:46

-

@supercat: the old joke, I don't need to outrun the bear, I just need to outrun you. – Ross Millikan Apr 19 '16 at 23:50

Predators always have to be much better hunters than the prey - they must eat every few days after all. But they can only get so good.

Predator/prey population balance will tend to look like a competition where if the predators are too efficient they will kill off the prey. If that happens they start to starve to death.

If the prey outrun the predators (or at least escape all the time) then the predators will starve to death. Then they breed until there are so many that they eat all the grass/vegetation and then they die off.

While both of these have certainly happened in natural history what is more stable for predators and prey to evolve in competition with each other such that their populations look like a stable equilibrium. If not, one of the would just disappear. Then later via migration another animal would come in to replace them.

- 28,244

- 2

- 60

- 120

-

5The first paragraph sounds a little wrong and seems to contradict the so called "life-dinner principle". – Remi.b Apr 19 '16 at 06:45