I think that you are misquoting Aliasing.

Digital acoustics is explained in a mathematical sense, Aliasing is a maths concept. Real life acoustics is explained in a physical sense, which talks about reflection, absorption, phase change, harmonic modes, weights... the perception of sound is discussed as psychoacoustics and cortical structures and individual nerve impulse detection thresholds. consider for example the explanation of drum acoustics, it is not digital and on no physical objects will you see the word "Aliasing" used: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vibrations_of_a_circular_membrane

Aliasing refers to a digital concept, whereby we devide screens into pixels, and you can't make out objects narrower than a pixel. A wave is at least 2 "/////" points of data, so it requires a 2x window so we have 44k CD's to code 22Khz sounds.

I'll just tackle this precise question, aside from the mis-use of the term Aliasing: why would I hear nothing instead of the signal aliased at a 30 kHz sampling rate?

Pressure waves are continuous and physical sounds... A continous sound or physical object can't be subject to the digital distortion effect "Aliasing" which for example refers to the generation of infinitely high frequencies in between two sampled points of a clock rate...

Because physical sound is continuous, it can't have frequency distortion related to it's sampling rate of 15/30 Khz, it can attenuate and physically react with physical objects including other sound pressure waves and cause physical objects to resonate in different modes of movement.

The sound detection depends on the physical excitation of hairs and nerves that must exceed a threshold of detection. physical objects don't have radical and odd excitation modes when they absorb a frequency that is too high, they can resonate in different modes, but they wack about wildly and produce volume clipping and sound artefacts. Most of the time they don't have a limit of frequency after which they go crazy. the closest you can get to strange frequency modes in physical objects is resonance where the movement builds up into a high kinetic movement like the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. You have to approach the ear as a physical model and not a digital one. I think of the resonant modes of structures in the ear similar to a guitar string or a gong moving in 3D space. This gives you an idea of the nerve signals in the ear:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1JE8WduJKV4&t=17s

Almost all sound that is detected inside an ear is distorted by reflection from it's initial shape and source, and thereby it is smudged into reverb similar to light travelling through frosted windows.

Human brains and tissues are not digital and quantized, they aren't even analog, the are cellular with different types/sizes of receptor cells and nerves, variable and organic. You can say they alias only when you talk about perfectly equal sized cell matrix in 2d/3d pattern, like photoreceptors, except that our minds disregard information on cellular scales that aren't useful to us, like a biological version of aliasing would be.

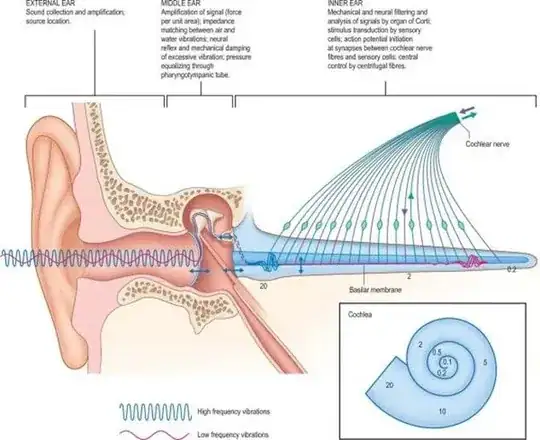

If you study the function of the cochlea you will find that the structures, hairs, membranes are so different from a digital aliasing concept.

Human ears collect high frequency sounds unlike the dished ears of bats and cats and dogs, which are made of stiff cartilage that reflects higher frequencies well, into the ear canal. high frequencies are absorbed very fast by the skin and it takes specialized organs to reflect them to stiff cartilage chambers lined with hairs, each part of which is adapted to further reflect and absorb different frequencies.

The cochlea is organic and cellular, and it is similar to multiple electret microphone diaphragms and cilia all existing inside a complex organ which sends the vibrations to nerves. Sounds have to be collected by dishing and focused onto light and rigid membranes.

There is very much artifacting from all frequencies as they reach the ear. The sounds reflect of different surfaces, although high frequency ones absorb more easily and therefore are heard more linear from the source to the sensor, and have more time precision and more binaural precision.

Sounds don't tend to be generated in the exact same spot(point sources), so if you have for example an insect generating high frequencies, it will make a complex wave shape, that excites a large envelope of air around it, like dropping 5-10 stones into some water, and the outgoing wave will not be a simple form, but a complex series of phase interactions similar water that is excited by a swimmer. In that sense it has some properties of a moiré pattern, but it isn't aliasing, it's complex wave and phase interaction.

An Aliased oscillator on the other hand is a digital sound which contains infinitely high frequencies, because digital encoding forces sudden changes in amplitude to be abrupt, which is different to nature, where sounds are continuous and not discrete sets of values.

As sound travels through air and through flesh, the high frequencies which are all pure sine wave components of the overall sound, will simply be attenuated according to complex spectra of attenuation which correspond to the ambient air conditions, the angle of incidence towards the reflective and transmitting ear vestibules.