(Using Blender 3.6.5)

NB: This post is to illustrate/to demonstrate/to complement Robin Betts's answer.

Objective

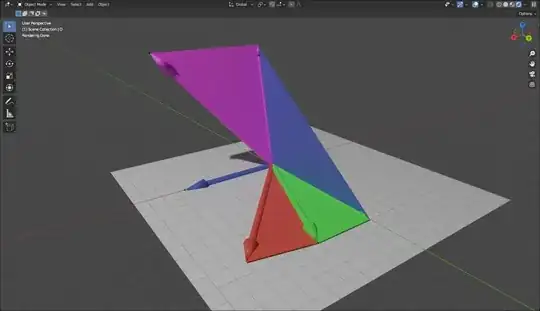

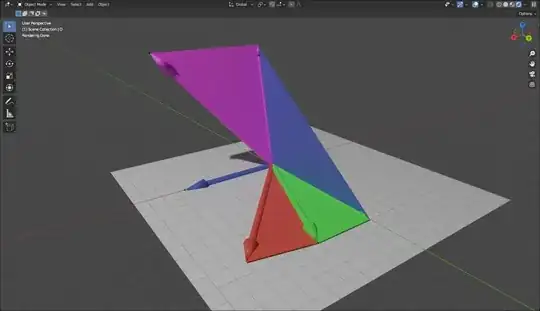

Let $\vec{N}$ (in blue), $\vec{A}$ (in magenta), $\vec{B}$ (in green) be three vectors such that $\vec{N}$ is not collinear to $\vec{A}$, neither to $\vec{B}$. The objective is to compute the rotation angle around the axis defined by $\vec{N}$, bringing $\vec{A}$ to be coplanar to $\vec{N}$ and $\vec{B}$ (in red).

Mathematics

Rotation around the axis defined by $\vec{N}$ is affecting only the vector components projected in a plane perpendicular to $\vec{N}$ (illustrated by the blue triangle). The vector component align with $\vec{N}$ is unchanged.

Let $\vec{A}^\perp$ and $\vec{B}^\perp$ be the restrictions of $\vec{A}$ and $\vec{B}$ perpendicular to $\vec{N}$ (illustrated as thinner vectors connected by triangles of same colour). These are defined by removing the projection along the axis, as:

$$\left\{ {\begin{array}{rcl}

\vec{A}^\perp & = & \vec{A} - (\vec{A} \cdot \vec{n}) \times \vec{n} \\

\vec{B}^\perp & = & \vec{B} - (\vec{B} \cdot \vec{n}) \times \vec{n}

\end{array}} \right.

$$

where $\vec{n} = \vec{N} / \| \vec{N}\|$ is the unitary vector align with the axis.

From the definitions of dot product and cross product,

$$\left\{ {\begin{array}{rcl}

\vec{A}^\perp \cdot \vec{B}^\perp & = & \| \vec{A}^\perp \| \times \| \vec{B}^\perp \| \times \cos{\alpha} \\

\vec{A}^\perp \wedge \vec{B}^\perp & = & \| \vec{A}^\perp \| \times \| \vec{B}^\perp \| \times \sin{\alpha} \times \vec{n}

\end{array}} \right.

$$

where $\alpha$ is the signed angle from $\vec{A}^\perp$ to $\vec{B}^\perp$, $\tan{\alpha}$ is computed as:

$$ \tan{\alpha = \frac{\sin{\alpha}}{\cos{\alpha}} = \frac{(\vec{A}^\perp \wedge \vec{B}^\perp) \cdot \vec{n}}{\vec{A}^\perp \cdot \vec{B}^\perp}}$$

Taking advantage of $\vec{n} \cdot \vec{n} = 1$, $\vec{A}^\perp \cdot \vec{B}^\perp$ is written:

$$\vec{A}^\perp \cdot \vec{B}^\perp = \vec{A} \cdot \vec{B} - (\vec{A} \cdot \vec{n}) \times (\vec{B} \cdot \vec{n})$$

Taking advantage of $\vec{n} \wedge \vec{n} = \vec{0}$ and of $\vec{U} \wedge \vec{n} \perp \vec{n}$, $(\vec{A}^\perp \wedge \vec{B}^\perp) \cdot \vec{n}$ is written:

$$(\vec{A}^\perp \wedge \vec{B}^\perp) \cdot \vec{n} = (\vec{A} \wedge \vec{B}) \cdot \vec{n}$$

As a conclusion:

$$\tan{\alpha} = \frac{(\vec{A} \wedge \vec{B}) \cdot \vec{n}}{\vec{A} \cdot \vec{B} - (\vec{A} \cdot \vec{n}) \times (\vec{B} \cdot \vec{n})}$$

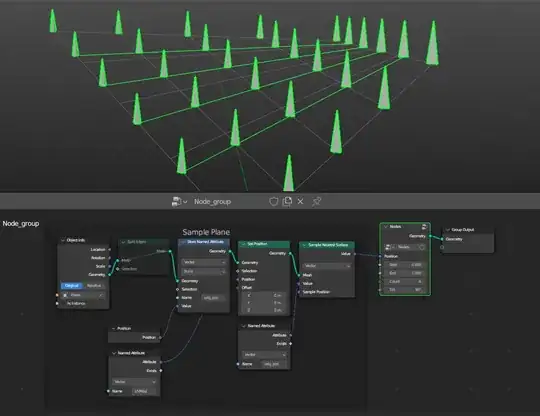

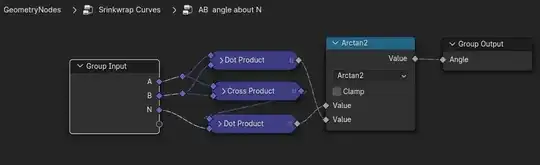

Geometry Nodes graph

Without hypothesis for $\vec{N}$, $\vec{A}$ and $\vec{B}$, $\alpha$ can then be computed with the following Node Group:

Resources

Blender file:

Moving vertices A,B and N, different configurations can be dynamically simulated.

Desired result, note the normal/tilt of the curve adhering to the normals of the plane (i've used instance on points as demonstration, but not what I'm after):

Desired result, note the normal/tilt of the curve adhering to the normals of the plane (i've used instance on points as demonstration, but not what I'm after):

The idea was to have the instanced curves be two points 0 - 1, with the tilt interpolated between the two. So point 0 will match the normal of its location on the surface and point 1 the normal of it's location with a consistent Z axis pointing away from the surface along the curve. Accuracy isn't too important.

– special_frog Jan 24 '24 at 09:51