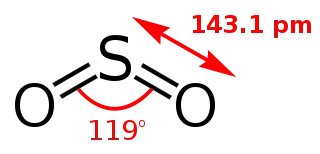

Figure 1: Structural data of $\ce{SO2}$. Taken from Wikimedia, where a full list of authors is available.

As can be seen from the structural data, the bond angle of $\ce{SO2}$ is almost precisely $120°$, meaning that the σ-orbitals can be described as almost perfect $\mathrm{sp^2}$ orbitals. This means that the sulphur lone pair is also in an $\mathrm{sp^2}$-like orbital while the fourth orbital of sulphur is of p-type to build a π-system not unlike that of the allyl anion. If sulphur were in the second period, this structure would not be surprising and indeed that of ozone is very similar (see figure 2).

Figure 2: structural data of $\ce{O3}$. Taken from Wikimedia, where a full list of authors is available.

However, atoms of the third and higher periods generally have bond angles which are much closer to $90°$ as can be seen in figure 3 with the structure of $\ce{SF2}$. Typically, this is explained by their greater size which results in larger bond lengths and smaller bond angles, allowing for increased s-character of the remaining lone pairs. I myself have argued in this manner in previous answers. This should suggest an $\ce{SO2}$ bond angle much closer to $90°$, maybe around $100°$ degree as we indeed observe for $\ce{SF2}$ (see figure 3).

Figure 3: Structural data of $\ce{SF2}$. Taken from Wikimedia, where a full list of authors is available.

But sulphur dioxide’s bond angle is $119°$ as stated above. Why does sulphur adopt such a large bond angle? Which factors disfavour the approximately $90°$ arrangement?