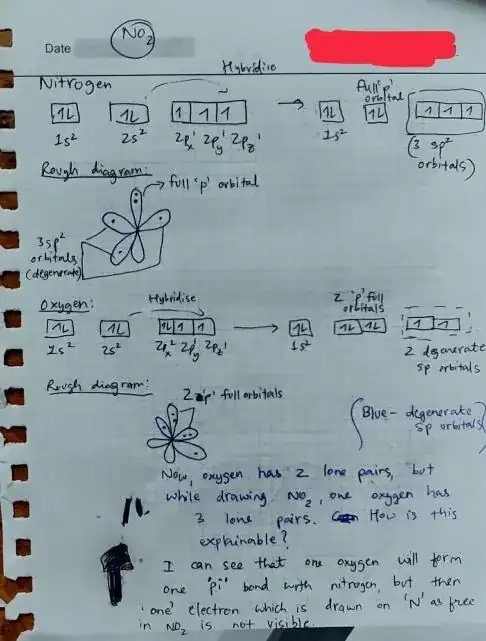

In your simple model, you start off with:

- nitrogen: $\mathrm{3(sp^2)^1 + p^2}$

- left oxygen: $\mathrm{(sp)^1 + sp^2 + p^1 + p^2}$

- right oxygen: $\mathrm{(sp)^1 + sp^2 + p^1 + p^2}$

The σ bonds are easy. Use $\mathrm{sp(O) + sp^2(N)}$. That leaves you with:

- left oxygen: $\mathrm{sp^2 + p^2 + p^1 + (\sigma_\ce{O-N})^2}$

- nitrogen: $\mathrm{p^2 + (sp^2)^1 + (\sigma_\ce{N-O(1)})^2 + (\sigma_\ce{N-O(2)})^2}$

- right oxygen: $\mathrm{sp^2 + p^2 + p^1 + (\sigma_\ce{N-O})^2}$

Now the question is how to do a π system (obviously there can only be one σ bond between two atoms). The orbitals used for the π system must be orthogonal to the bond axis, since that axis must be a node. Both oxygens have two p-type orbitals which fulfill this condition. Nitrogen also must use its p-type orbital to form the π bond. The $\mathrm{sp^2}$ orbital cannot because it is in the same plane as the other two $\mathrm{sp^2}$ orbitals, angled at $120^\circ$ rather than $90^\circ$. This gives us a π system composed of two oxygen p orbitals (one on each oxygen) and one nitrogen p orbital; choosing our orbitals well will result in this π system having four electrons. Essentially, this is theme and variation of Your Average 4-electron-3-centre bonding; but you can also consider it akin to the allyl anion.

The one remaining unpaired orbital would be in $\mathrm{sp^2}$ on nitrogen, pointing away from both $\ce{N-O}$ bonds but being in the same plane.

The above are the considerations and reasonings that you should use from the starting point you had. It is not the only way. You could assume that nitrogens five electrons are actually distributed as $\mathrm{2(sp^2)^1 + (sp^2)^2 + p^1}$. In this case, the argument outlined above is essentially the same except that the π system now contains three electrons rather than four; it is an allyl radical system, if you wish. Since this ab initio construction will lead to all orbitals with s contribution ($\mathrm{sp^2}$ on nitrogen, $\mathrm{sp}$ on oxygen) being fully occupied, it is more consistent with Bent’s rule and likely to be a better proposition.

If you do it like this, you can – in the Lewis 2-electron-2-centre formalism – choose either oxygen and have the radical form an $\ce{N-O}$ π bond on that side; the other will remain a radical. By resonance, you can draw the mirrored molecule.

$$\ce{O=N-\overset{.}{O} <-> \overset{.}{O}-N=O}$$

In these structures, the radical is never centred on nitrogen although we find that dimerisation at low temperatures leads to $\ce{O2N-NO2}$.

Actual measurement shows, that the radical is centred in an orbital that transforms as $\mathrm{a_1}$. As $\mathrm{a_1}$ is symmetric with regards to all symmetry transformations, it cannot be a π type orbital which can transform either as $\mathrm{a_2}$ (node through nitrogen) or $\mathrm{b_1/b_2}$ (no node through nitrogen; depending on your choice of coordinates). You see, it gets more and more complicated the more you rely on experimental data.