I think your question implicates another question (which is also mentioned in some comments here), namely: Why are all energy eigenvalues of states with a different angular momentum quantum number $\ell$ but with the same principal quantum number $n$ (e.g., $\mathrm{3s}$, $\mathrm{3p}$, $\mathrm{3d}$) degenerate in the hydrogen atom but non-degenerate in multi-electron atoms?

Although AcidFlask already gave a good answer (mostly on the non-degeneracy part) I will try to eleborate on it from my point of view and give some additional information.

I will split my answer in three parts: The first will address the $\ell$-degeneracy in the hydrogen atom, in the second I will try to explain why this degeneracy is lifted, and in the third I will try to reason why $\mathrm{3s}$ states are lower in energy than $\mathrm{3p}$ states (which are in turn lower in energy than $\mathrm{3d}$ states).

$\ell$-degeneracy of the hydrogen atoms energy eigenvalues

The non-relativistic electron in a hydrogen atom experiences a potential that is analogous to the Kepler problem known from classical mechanics.

This potential (aka Kepler potential) has the form $\frac{\kappa}{r}$, where $r$ is the distance between the nucleus and the electron, and $\kappa$ is a proportionality constant.

Now, it is known from physics that symmetries of a system lead to conserved quantities (Noether Theorem).

For example from the rotational symmetry of the Kepler potential follows the conservation of the angular momentum, which is characterized by $\ell$. But while the length of the angular momentum vector is fixed by $\ell$ there are still different possibilities for the orientation of its $z$-component, characterized by the magnetic quantum number $m$, which are all energetically equivalent as long as the system maintains its rotational symmetry.

So, the rotational symmetry leads to the $m$-degeneracy of the energy eigenvalues for the hydrogen atom.

Analogously, the $\ell$-degeneracy of the hydrogen atoms energy eigenvalues can also be traced back to a symmetry, the $SO(4)$ symmetry.

The system's $SO(4)$ symmetry is not a geometric symmetry like the one explored before but a so called dynamical symmetry which follows from the form of the Schroedinger equation for the Kepler potential.

(It corresponds to rotations in a four-dimensional cartesian space. Note that these rotations do not operate in some physical space.)

This dynamical symmetry conserves the Laplace-Runge-Lenz vector $\hat{\vec{M}}$ and it can be shown that this conserved quantity leads to the $\ell$-independent energy spectrum with $E \propto \frac{1}{n^2}$. (A detailed derivation, though in German, can be found here.)

Why is the $\ell$-degeneracy of the energy eigenvalues lifted in multi-electron atoms?

As the $m$-degeneracy of the hydrogen atom's energy eigenvalues can be broken by destroying the system's spherical symmetry, e.g., by applying a magnetic field, the $\ell$ degeneracy is lifted as soon as the potential appearing in the Hamilton operator deviates from the pure $\frac{\kappa}{r}$ form.

This is certainly the case for multielectron atoms since the outer electrons are screened from the nuclear Coulomb attraction by the inner electrons and the strength of the screening depends on their distance from the nucleus.

(Other factors, like spin and relativistic effects, also lead to a lifting of the $\ell$-degeneracy even in the hydrogen atom.)

Why do states with the same $n$ but lower $\ell$ values have lower energy eigenvalues?

Two effects are important here:

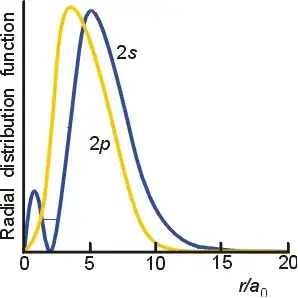

The centrifugal force puts an "energy penalty" onto states with higher angular momentum.${}^{1}$ So, a higher $\ell$ value implies a stronger centrifugal force, that pushes electrons away from the nucleus.

- The concept of centrifugal force can be seen in the radial Schroedinger equation for the radial part $R(r)$ of the wave function $\Psi(r, \theta, \varphi) = R(r) Y_{\ell,m} (\theta, \varphi )$

\begin{equation}

\bigg( \frac{ - \hbar^{2} }{ 2 m_{\mathrm{e}} } \frac{ \mathrm{d}^{2} }{ \mathrm{d} r^{2} } + \underbrace{ \frac{ \hbar^{2} }{ 2 m_{\mathrm{e}} } \frac{ \ell (\ell + 1) }{ r^{2} } } - \frac{ Z e^{2} }{ 2 m_{\mathrm{e}} r } - E \bigg) r R(r) = 0

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

{}^{= ~ V^{\ell}_{\mathrm{cf}} (r)} \qquad \qquad

\end{equation}

The radial part experiences an additional $\ell$-dependent potential $V^{\ell}_{\mathrm{cf}} (r)$ that pushes the electrons away from the nucleus.

Core repulsion (Pauli repulsion), on the other hand, puts an "energy penalty" on states with a lower angular momentum. That is because the core repulsion acts only between electrons with the same angular momentum${}^{1}$. So it acts stronger on the low-angular momentum states since there are more core shells with lower angular momentum.

- Core repulsion is due to the condition that the wave functions must be orthogonal which in turn is a consequence of the Pauli principle. Because states with different $\ell$ values are already orthogonal by their angular motion, there is no Pauli repulsion between those states. However, states with the same $\ell$ value feel an additional effect from core orthogonalization.

The "accidental" $\ell$-degeneracy of the hydrogen atom can be described as a balance

between centrifugal force and core repulsion, that both act against the nuclear Coulomb

attraction.

In the real atom the balance between centrifugal force and core repulsion is broken,

The core electrons are contracted compared to the outer electrons because there are less inner electron-shells screening the nuclear attraction from the core shells than from the valence electrons.

Since the inner electron shells are more contracted than the outer ones, the core repulsion is weakened whereas the effects due to the centrifugal force remain unchanged. The reduced core repulsion in turn stabilizes the states with lower angular momenta, i.e. lower $\ell$ values. So, $\mathrm{3s}$ states are lower in energy than $\mathrm{3p}$ states which are in turn lower in energy than $\mathrm{3d}$ states.

Of course, one has to be careful when using results of the hydrogen atom to describe effects in multielectron atoms as AcidFlask mentioned. But since only a qualitative description is needed this might be justifiable.

I hope this somewhat lengthy answer is helpful. If something is wrong with my arguments I'm happy to discuss those points.