Why is hydrated carbon dioxide - the predominant form of acid that one gets upon dissolution of carbon dioxide in solution - so unstable?

Is the below rationale valid?

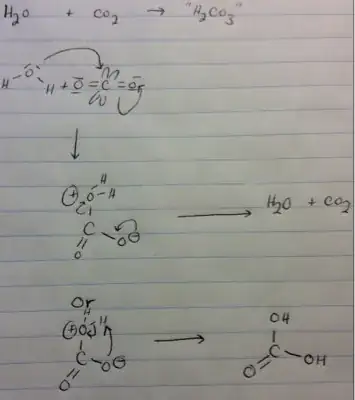

- Carbon in carbon dioxide has two (empty? no, but still vulnerable to attack) p-orbitals and bears a strong partial positive charge.

- Oxygen's lone pair can attack an empty p-orbital and form a formal charge-separated complex with the carbon dioxide.

- This is "hydrated" carbon dioxide or "carbonic acid." This form is extremely unstable and subject to disproportionation due to an unfavorable charge and the unfavorable nature of charge separation itself. The change in entropy also favors the products of disproportionation.

- However, there exists a pathway to stability - that is - protonation of the oxygen with the negative formal charge by the oxygen bearing the positive formal charge.

- This, however, is akin to a forbidden fruit; the ephemeral three-membered ring that would have to be formed exhibits "ring strain" (if you object to this term, can you please elaborate on your objection), and as a result, disproportionation is overwhelmingly favored, especially from an entropic standpoint (reconstitution of carbon dioxide gas is highly entropically favorable).