The interaction potentials of the two cases you propose are dramatically different, because the Coulombic interactions are dramatically different. In one case you are talking about the interaction of two particles with opposing charge, in the other of two neutral particles:

$$\begin{align}\ce{Na(g) ... ... Cl(g) } ~~~~~~ & \textrm{very weak electrostatic interaction}\\ \ce{Na+(g) ... ... Cl-(g) }~~~~~~& \textrm{strong electrostatic interaction}\end{align}$$

In the first case you can essentially ignore interactions between the particles until they are within a distance of the order of the sum of their van der Waals radii. In other words, until very close the particles behave as in an ideal gas. If the neutral particles collide they might share electrons and bond covalently or, somewhat more likely, exchange an electron to form ions and an ionic bond. The actual bond that may form will be intermediate to these extremes and closer to ionic.

In the second case the particles attract strongly even at fairly large distances due to the $r^{-1}$ Coulombic potential. This is a very unstable situation. The attraction may lead to a collision if the particles do not fly too fast and too far apart.

A bond formed during a collision will be stable provided the collision energy was not too great, otherwise the particles will bounce off each other. They might then retain any charges gained through the collision. These topics are the subject of gas phase molecular dynamics. See for instance Ref 1.

When the neutral Na and Cl pairs come close to each other, potential energy is released, but why is it now energetically more favorable when Na transfers its electrons with this released energy to the Cl? Wouldn't the potential energy be even more negative if they came closer and didn't transfer anything?

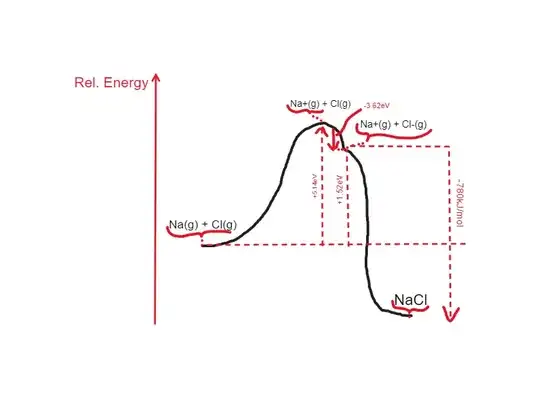

Since the potential between uncharged particles changes very little as you bring them closer, whereas that of oppositely charged ones decreases much more rapidly, a transfer from the neutral to the charged potential energy curves becomes increasingly favorable as the particles get closer. Eventually the change in the attractive potential between the charged particles compensates for the cost of transferring an electron between the atoms and the transfer becomes viable and may occur spontaneously (for instance through quantum tunneling). This is illustrated in the following figure (distance is in units of Bohr radius):

Various sites including this one report that this happens when the internuclear distance falls below 9.4 Å.

However, I have no answer for what is the probability of an electron transfer between gas phase sodium and chlorine as a function of interatomic distance. In essence that is what a large part of your post boils down to.

References

(1) Šimsová née Zámečníková, M.; Gustafsson, M.; Soldán, P. Non-Adiabatic Dynamics in Collisions of Sodium and Chlorine Atoms and Their Ions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24 (41), 25250–25257. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2CP03361E.