The answer to a similar question is not sufficient to fully understand it. At least it gives a useful picture where it is noticeable that the melting point depends on the nuclear charge, because most of the elements in the sixth period, where the potential is less shielded by $d$ and $f$ orbitals, have the highest melting point. I will explain the electronic part:

$\ce{Cr}$ forms a solid-state metal, its melting point is related to solid state properties and not directly to the atomic configuration. These properties depend on the structure and the electronic configuration. The solution of the Schrödinger equation in this case does not keep the shape of the atomic orbitals, but delocalized wave function tending to plane waves, some approximations keeps atomic orbitals to describe metals, but they aren't very accurate. Because the solid combines a large number of atoms, the molecular levels have a tiny space giving a continuous band structure. The width of the band structure describes a rate of transfer $t$ of an electron from one site to another; if this rate is high enough, the repulsion can be neglected. $t$ is related to the bond strength, and the bond strength is related to the melting point.

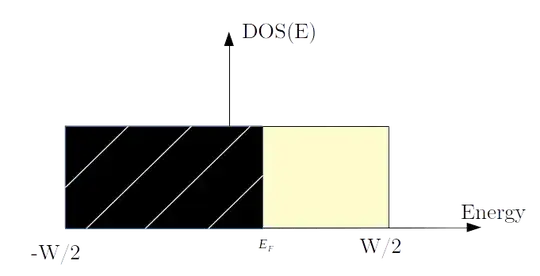

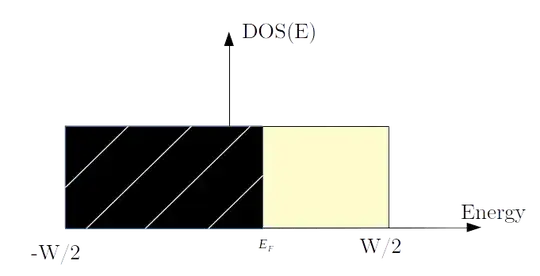

The previous arguments are difficult to put into an analytical form, the most accurate analytical band structure is that of a homogeneous electron gas where the dispersion is quadratic $E \propto k^2$, as the electrons are interacting in a metal, this dispersion relation is not accurate in this case, moreover the $d$ orbitals are localized and do not overlap much (the repulsion is very important as the transfer rate $t$ is smaller). Instead of trying to solve a complex many-body equation to calculate the binding energy, we can use an approximate density of states (DOS). The $d$ orbitals are farther away from the nucleus and have the largest number of electrons in the case of $\ce{Cr}$, so they have the most influence on the bond energy. Since $t$ is small, the bandwidth $W$ is also small and the density of states (DOS) is narrow, a rectangular approximation is often used:

The figure above gives the density of states, where the surface of black part is the number of electrons of the metal filling the bands: $n_d$, the surface of remaining part is the number of empty states at $\bf{T=0}$ K. The energy of a bond is the difference between the sum of the energies of all states from $-W/2$ to the Fermi energy $E_F$ and the atomic energy of the $d$ orbital considered as degenerate.

$$E_{bond} = \int_{-w/2}^{E_F} E \cdot DOS(E) dE - E_{d,at}$$

$E_{bond}$ is similar to the enthalpy of atomisation or a cohesive energy. As $d$ orbitals have $10$ electrons :

$n_e= \int_{-w/2}^{W/2} E \cdot DOS(E) dE = DOS(E)\cdot W = 10$, $DOS(E) = \frac{10}{W}$ and $n_d=\int_{-w/2}^{E_f} DOS(E) dE = \frac{10}{W} (E_F+W/2)=\frac{10}{W} (E_F+5)$. Therefore $E_{bond}$ gives :

$$E_{bond} = \frac{10}{W} \int_{-w/2}^{E_F} E dE - E_{d,at} =\frac{W^2}{20} \left[ (n_d^2-5)^2 -25\right] - E_{d,at} $$

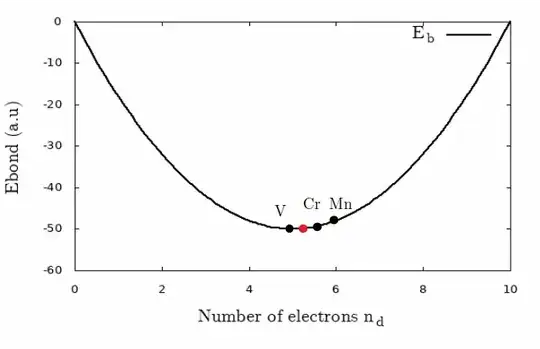

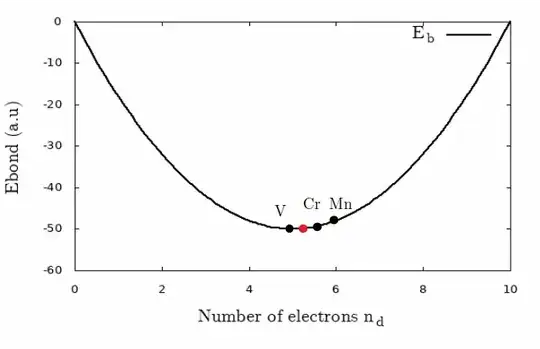

The bond energy starts at zero when the filling is zero and decreases to the minimum when the $d$ "band" is half filled and increases to the value when the band is completely filled. The lowest value is a "band" half filled (red dot), it may be surprising but as shown in the figure below ($W/20=E_{at}=1$) that neither chromium, manganese nor vanadium sits at the minimum, it is a choice due to the charge distribution in a solid compared to isolated atoms which I have tried to explain here. In fact, the partial charge in a specific orbital of an atom forming a solid is rarely equal to the free atomic charge of this orbital, it is due to the fact that $s$ and $d$ orbitals are involved in the metallic bonds, a partial charge from the $s$ orbital (closer to the nucleus) is transferred to the $d$ band, resulting more charge in the $d$ band and then less bond energy for manganese (who has half-filled $d$ orbitals). The process occurs with chromium with half-filled atomic orbitals, but the charge in the $d$ band is more than charge of the free atom, the bond energy id higher than the minimal value. The closer is vanadium, which tends to the minimum and has less electronic repulsion, therefore has the highest melting point, then comes chromium, and so on. This approximation seems crude at first, but in the end it is very efficient.

But if we consider this as a reason it does not correctly explains the higher melting point among the 4-period transition metal.

Could you explain what could be possibly wrong with either of this explanation?

Vanadium has the highest melting point, when I studied this metal in the past, the charge in the $d$ band was not too far from the atomic charge, there are certainly other effects to include and question is about chromium. In the case of $\ce{Cr}$, the considerations above are one approximation to explain the anomaly with manganese, the charge $n_d$ of $\ce{Ce}$ is also similar to the atomic charge of $d$ orbitals, but in the case of $\ce{Mn}$, $n_d > 5 $ and the melting point drops.