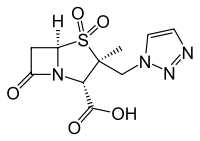

One of the drugs I work with is a beta-lactam (4-membered ring with an amide bond) fused to a sulfone ring, tazobactam.

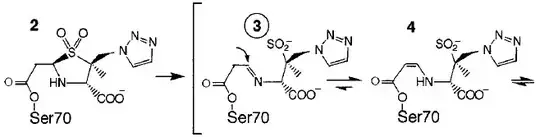

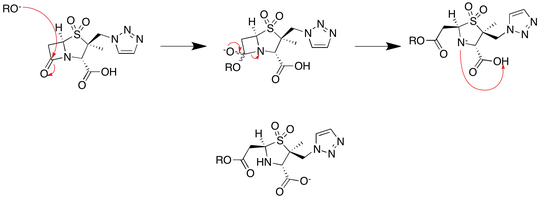

It's relatively stable in water; the lactam is not significantly hydrolyzed without being catalyzed. When the lactam is hydrolyzed, however, typically by an enzyme, and the lactam ring opened, the sulfone ring also opens cleaving the bond between the sulfur and bridgehead carbon. A paper by Kuzin gives the following reaction scheme (this is part of figure 2, click for the whole thing)

and says of it (emphasis mine):

The Ser70-bound moiety (2) is thought to be the initial intermediate [...] Ring opening after departure of the sulfinate from C5 produces a reactive imine (3) and the more inert tautomeric enamine forms (4, 5).

But why is the sulfuryl (sulfone, sulfonyl(?)...) leaving only when the lactam is opened and not spontaneously beforehand?

Other fused bicyclic beta-lactam drugs don't open the other ring, where in lieu of the sulfone there is commonly a thioether (as in penicillin). The sulfone group seems more electron hungry, but I don't see how the broken lactam bond affects this.

I've heard some people suggest that the lone pair on the nitrogen is able to make this happen, but why doesn't it then happen in the intact drug?