$$\ce{2Na(l) +2NH3 (g) ->2NaNH2(s) + H2(g)}$$

$$\ce{CH3Cl (alc) +NH3 (alc) -> CH3NH2 (alc) +HCl(alc)}$$

Doesn't ammonia donate a proton in both cases?

$$\ce{2Na(l) +2NH3 (g) ->2NaNH2(s) + H2(g)}$$

$$\ce{CH3Cl (alc) +NH3 (alc) -> CH3NH2 (alc) +HCl(alc)}$$

Doesn't ammonia donate a proton in both cases?

Ammonia has a $\mathrm{p}K_{\mathrm{a}}$ value (a description what that means can be found in this answer of mine) of 33 and is thus not acidic at all - you'd need a $\mathrm{pH}$ value around 30 to deprotonate $\ce{NH3}$ to any appreciable amount! This means that $\ce{NH3}$ very rarely acts as a proton donor itself.

So, what happens in your first reaction is the following: It is widely known that when you dissolve $\ce{Na}$ in liquid ammonia you get solvated electrons (in the form of electride complexes). But electrons have of course very strong reducing power, so after a while they attack $\ce{NH3}$ abstracting one of its $\ce{H}$ atoms under the liberation of hydrogen gas. The important point here is that there is no dissociation of $\ce{NH3}$ here, i.e. no reaction $\ce{NH3 <=> NH2^{-} + H^{+}}$, so $\ce{NH3}$ does not act as a proton donor in the same sense a Bronsted acid would.

Your second reaction is an $\mathrm{S}_{\mathrm{N}}2$ reaction where $\ce{NH3}$ acts as a nucleophile. So, it doesn't act as a proton donor in this reaction neither. What it does is that it replaces (substitutes) the $\ce{Cl}$ in $\ce{CH3Cl}$, thus forming a methylammonium salt, $\ce{CH3NH3^{+}Cl^{-}}$.

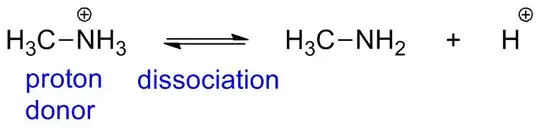

Now, the $\mathrm{p}K_{\mathrm{a}}$ of an alkylammonium cation lies somewhere around 10 (the $\mathrm{p}K_{\mathrm{a}}$ of $\ce{NH4^{+}}$ is 9.24). So, it is much more acidic than $\ce{NH3}$ and also more acidic than the surrounding alcohol (I assume that "(alc)" means that the reaction is done in alcohol), which has a $\mathrm{p}K_{\mathrm{a}}$ between 15 and 17, and thus it (the ammonium salt) acts as a proton donor.