Resonance is a remnant of valence bond theory, which is necessary because it is impossible to describe delocalised bonding within a localised bonding scheme. Resonance structures are not real. One Lewis structure describes one electronic configuration with fully localised electrons. For many molecules it is completely sufficient to describe the bonding situation with one such structure in a first order approximation. For many other molecules this is completely insufficient. For $\ce{NO2-}$ this is the case, hence you need a superposition of more than one structure to get closer to a qualitative description. This caveat is not necessary in molecular orbital theory, since this is designed to treat delocalisation.

Nitrite anion

One question therefore arises from the above: Are the $\ce{N-O}$ bond lengths equal because there is resonance, or is there resonance because the $\ce{N-O}$ bond lengths are equal?

This is obviously more of a philosophical question, but it shows the dilemma of the whole concept. The bonding of any given molecule is a result of many different factors; to name but a few: repulsion of the nuclei, repulsion between the electrons, attraction between electrons and nuclei.

For $\ce{NO2-}$ there is one key question, that gives us a very important clue as to why the bond lengths are equal: Why should one oxygen atom be different from the other? In fact the molecule is symmetric (C2v), therefore the bond lengths must be equal.

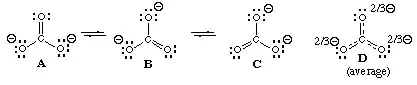

If you try to write a Lewis structure that respects this symmetry, you will end up with an electron sextet on nitrogen (and a formal charge of +2), which certainly can only be an insufficient approximation. If you write a Lewis structure with fewer formal charges, keeping symmetry, you will notice that nitrogen will have 10 electrons. That would mean that it would have to use d-orbitals, which simply are not available for nitrogen (more on that another time). There is another way to write a Lewis structure, however, this one has to break the symmetry, and you'll notice that there is a second one, which is equal. In order to keep the symmetry you introduce resonance, to state, that the "true" electronic structure is a superposition of (at least) those two configurations.

TL;DR: The $\ce{N-O}$ bonds in the nitrite anion are equal, because the oxygens are equal.

Nitrous acid

It is false to say that in $\ce{HONO}$ is no resonance. And it is also wrong to say that a lack of resonance makes the bonds unequal. If the solution manual claims this, it is wrong.

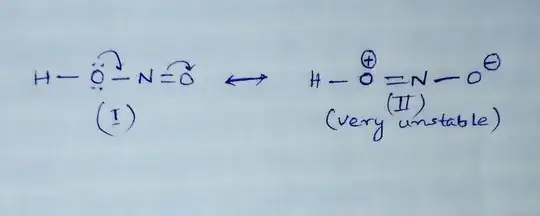

Why can $\ce{HNO2}$ not have 2 possible structures where the single and double bonds switch between the two oxygens?

These are valid resonance structures of nitrous acid. You have to keep in mind though, that resonance does not change the geometry of a molecule (or molecular structure). The contribution of the Lewis structure with fewer formal charges to the total wave function will be much higher than the contribution of the other structure in this case. This is not a general statement, there are molecules where the charge separated Lewis structure has a higher contribution to the wave function.

By analogy to the anion case, there is one key question, that gives us a clue about the molecular structure: If you bind a proton to one oxygen, are both oxygen really equal anymore? In this case the symmetry of the molecule is reduced to Cs. Therefore the bonds, cannot be equal.

For this molecule you will have no problem writing a single Lewis structure that satisfies every imposed criteria.

To answer the initial question: The bonds in $\ce{HONO}$ are unequal, because the proton is bound to one of the oxygens. It is a very polar, but covalent bond. The electron density of the $\ce{N-O}$ bond is therefore shifted towards the $\ce{H-O}$ bond, and simultaneously reduced for the $\ce{N-O}$ bond when compared to the anion. Therefore the $\ce{HO-N}$ bond is longer than the $\ce{N=O}$ bond (I implied the most contributing Lewis structure here).

TL;DR: The $\ce{N-O}$ bonds in the nitrous acid molecule are unequal, because the oxygens are unequal.

There frequently is the notion of a most stable resonance structure. While this is very popular, it is completely wrong. I again refer to the question What is resonance, and are resonance structures real? Resonance is used to describe the electronic structure of a molecule, there is no change in the molecular structure allowed. It is necessary to understand, that only the description in terms of all possible resonance structures is in itself correct, i.e. the theoretical limit of valence bond theory, everything else is an approximation. However, not all resonance structures will have the same contribution to the wave function. Whenever someone speaks of the most stable resonance structure, it is likely that they mean the resonance structure with the highest contribution to the wave function. But even if you know what is meant, it is still wrong to speak of a most stable resonance structure, it must be corrected.

(I currently don't have the time to provide a full fledged answer, so instead I was trying to give some pointers in the right direction. I might come back to amend it whenever I have more time.)