In general, when should I use liquid or solid IR spectrometry to analyse my compound? What should I expect to see? Would I see higher or lower frequency, broader or narrower transitions? My specific case is a tricobalt cluster, Co3(CBr)(CO)9. But I'm also curious for all compounds in general.

-

It depends, and your question reads like you're asking for a complete introductory lecture on IR. What's your educational background, and have you done literature research on what method people working on similar material use? If not, do so. ;-) – Karl May 28 '18 at 17:25

1 Answers

Some basic comments can be found in Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds. Although it is primarily concerned with interpretation, it has some notes on the types of instrumentation and samples that would typically be encountered in an (in)organic chemistry lab. I'll only reproduce parts that mention the quality of the obtained spectrum.

Vapor-phase spectra resemble those obtained at high dilution in a nonpolar solvent: Concentration-dependent peaks are shifted to higher frequency compared with those obtained from concentrated solutions, thin films, or the solid state (see Aldrich, 1989).

Thick samples of neat liquids usually absorb too strongly to produce a satisfactory spectrum. (...) For example, thick samples of carbon tetrachloride absorb strongly near 800 cm-1; compensation for this band (using a reference beam with pure solvent) is ineffective since strong absorption prevents any radiation from reaching the detector.

Solids are usually examined as a mull, as a pressed disk, or as a deposited glassy film. The suspended particles in a mull must be less than 2 microns (in diameter) to avoid excessive scattering of radiation. The quality of the spectrum (when using a pellet) depends on the intimacy of mixing and the reduction of the suspended particles to 2 microns or less.

In general, a dilute solution in a nonpolar solvent furnishes the best (i.e., least distorted) spectrum. Nonpolar compounds give essentially the same spectra in the condensed phase (i.e., neat liquid, a mull, a KBr disk, or a thin film) as they give in nonpolar solvents. Polar compounds, however, often show hydrogen-bonding effects in the condensed phase. Unfortunately, polar compounds are frequently insoluble in nonpolar solvents, and the spectrum must be obtained either in a condensed phase or in a polar solvent; the latter introduces the possibility of solute–solvent hydrogen bonding.

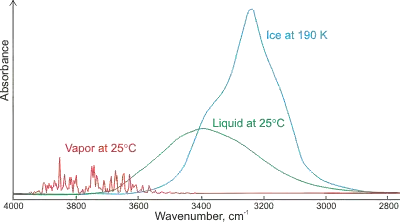

One of the reasons you don't want very concentrated samples (for structural determination) is that you increase the amount of intermolecular interaction present in the sample, which can change peak positions and widths. A prototypical example is water:

For the vapor (gas phase), the water molecules are almost non-interacting, leading to well-defined and narrow peaks. The structure here may still be from some small number of environments where a molecule is interacting with a handful of others, but it may also be rotational fine structure (see rovibrational spectroscopy). In the (condensed) liquid phase, these individually-identifiable peaks coalesce into one broad peak due to the many hydrogen bonding environments induced by collsion with other molecules. The ~400 cm-1 redshift of the peak center originates from the nature of a single hydrogen bond:

where the molecule on the right (the h-bond acceptor) donates electron density into the $\ce{O-H}$ bond of the molecule on the left (the h-bond donor), specifically an antibonding orbital, which weakens the bond. Weaker bonds are lower in energy, and wavenumbers (cm-1) are units of energy. Finally, for the solid phase, most common polymorphs of ice have regular structure with a finite number of hydrogen bonding environments, which leads to slightly more distinct peak structure in the solid over the liquid. These peaks are further redshifted due to the decreased $\ce{O-O}$ distance in ice over liquid water (2.76 versus 2.82 Å), leading to even greater charge transfer between water molecules. Broadening and shifting can be also seen for glycine peptides of different lengths prepared as both a solid mull and in continuous films due to the terminal $\ce{-NH3 / -NH2+}$ and backbone $\ce{-NH}$ groups.

I don't have any references for it right now, but you can also obtain peak broadening due to solute–solvent chemical exchange; I have only heard of this for hydrogen.

To summarize,

- increasing the number of distinct chemical environments for a particular vibrational oscillator is going to broaden the peak associated with that oscillator, and

- intermolecular interactions that directly alter the electron density of the vibrational oscillator are going to shift its peak position; whether it will redshift or blueshift roughly corresponds to a decrease or increase in bond order.

References

- Silverstein, Robert M.; Webster, Francis X.; Kiemle, David J. Infrared Spectrometry. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds, 7th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New Jersey, 2005; pp. 79-80.

- http://www1.lsbu.ac.uk/water/water_hydrogen_bonding.html

- Blout, Elkan R.; Linsley, Seymour G. Infrared Spectra and the Structure of Glycine and Leucine Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952, 74, 1946-1951.

- 7,488

- 6

- 47

- 78