I have to try and work this out using the tetrahedral molecular orbital diagram for $\ce{[WO4]^2-}$ but I am confused as both are $\mathrm d^0$ right?

-

2I think this is a great question about CT complexes $\ce{[M^{VI}O4]^2-}$ and can be further extended with examples for sulfate $\ce{SO4^2-}$ and molybdate $\ce{MoO4^2-}$ (both colorless) and uranate $\ce{UO4^2-}$ (yellow). – andselisk Jan 08 '20 at 13:42

-

@andselisk why is this the case? Is it to do with LMCT? – Fariha Jan 08 '20 at 14:10

-

What doesn't? The majority of metal complexes are colored precisely because of LMCT. – andselisk Jan 08 '20 at 14:15

-

@andselisk does that mean [WO4]2- does not have LMCT bands then because it appears colourless? Sorry I'm confused. – Fariha Jan 08 '20 at 14:29

-

LMCT bands may lie not only in visible, but also UV or NIR range. – andselisk Jan 08 '20 at 14:46

-

5@andselisk - This is getting off topic of the question, but I don't think it's accurate to say that the "majority" of metal complexes are colored because of LMCT. Intensely colored ones like dichromate and permanganate are, but many transition metal complexes are weakly colored because of $d \rightarrow d$ transitions, not LMCT. I think the majority of common complexes that students encounter are likely $d \rightarrow d$. – Andrew Jan 08 '20 at 15:17

-

@Andrew Yeah, I gave it a second thought and you are probably correct, it's just that I primarily encountered LMCT-type complexes in my research. Thanks for tuning in and correcting me. – andselisk Jan 08 '20 at 15:25

-

1https://chemistry.stackexchange.com/questions/39829/how-can-the-intense-color-of-potassium-permanganate-be-explained-with-molecular?noredirect=1&lq=1 https://chemistry.stackexchange.com/questions/27/color-of-chromate-and-permanganate – Mithoron Jan 08 '20 at 23:17

1 Answers

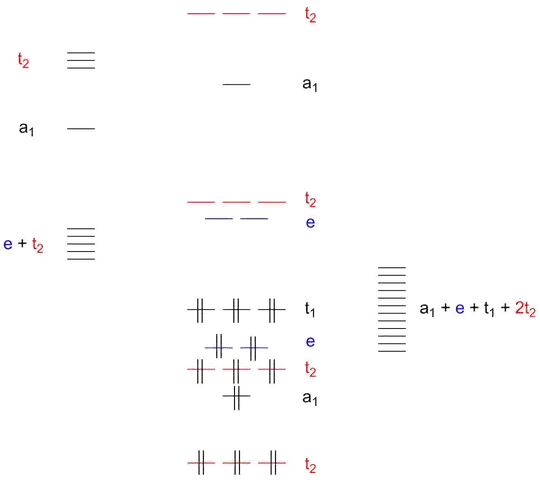

Both complexes (and many more such as permanganate, sulphate, …) share the same general MO scheme which I am going to shamelessly copy from my older answer:

Figure 1: Qualitative MO scheme of a tetrahedric complex with σ and π bonding between metal and ligands. Double vertical lines represent electron pairs.

The intense colour of permanganate and chromate is due to LMCT transitions: ligand-to-metal charge transfer. Essentially, an electron from the HOMO (a $\mathrm{t_1}$ orbital that can be thought of a ligand-centred p-type orbital) is excited to the LUMO (an $\mathrm{e}$-type orbital that can be thought of one of the metal’s empty d orbitals) by absorbing a photon from the visible range; we then see the complementary colour, meaning that chromate absorbs blue light and looks yellow to our eyes.

The energies of LUMO and HOMO – or rather, the energy difference between the two – determines the wavelength of the absorbed photon and thus the colour that we see. For both permanganate and chromate, the wavelength is well within the visible spectrum resulting in the strongly coloured complexes. In cases such as sulphate or tungstate, the absorption wavelength is in the ultraviolet range which cannot be perceived by human eyes; therefore, the solution appears uncoloured.

Without computer calculations, it is probably impossible to accurately predict the ultimate wavelength but note that such an absorption is practically always present if the corresponding orbitals are available although usually in the ultraviolet range. An obvious counterexample would be any zinc complex in which the metal has a $\mathrm d^{10}$ configuration and the LUMO is thus the much further removed $\mathrm a_1$ orbital; therefore, zinc complexes are typically colourless and do not display such an LMCT band.

- 67,989

- 12

- 201

- 386