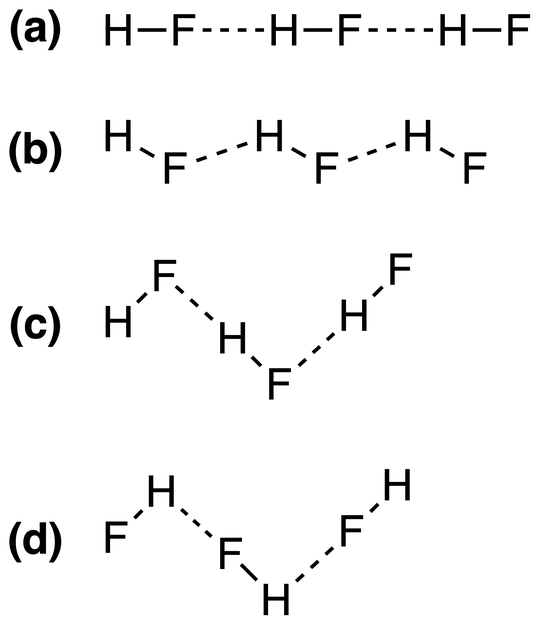

The correct combination of straight and bent bond angles may be explained with the molecular orbitals description of hydrogen bonding.

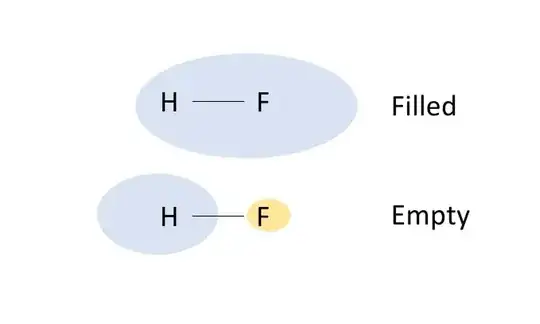

In an isolated hydrogen fluoride molecule the valence orbitals combine to give an occupied bonding orbital (upper orbital in the figure below) and an empty antibonding orbital (lower orbital):

Note the positioning: the lower-energy bonding orbital is concentrated between the atoms where the bond forms and also around the more electronegative fluorine atom, while the higher-energy antibonding orbital is mostly in less stable regions outside the bond and around the hydrogen atom.

Now introduce a second hydrogen fluoride molecule. In this molecule a nonbonding electron pair on the fluorine can overlap the antibonding orbital on the first molecule, which is mostly around the hydrogen atom; this slightly weakens the bobd within the first molecule but creates a bond between the two of them. The net additional bonding energy is the net hydrogen bonding energy. Because the nonbonding orbitals on fluorine are not aligned with the bond but the antibonding orbital is so aligned, the best hydrogen-bond overlap occurs when the geometry at hydrogen is linear but the geometry at fluorine is bent:

Molecules other than hydrogen fluoride, such as water, also tend to have molecular orbitals aligned along the bonds between hydrogen atoms and electronegative atoms, so these too commonly form the strongest intermolecular hydrogen bonds if the hydrogen is linearly between the neighboring atoms.