You cannot make (= synthesise) isolated, nonaromatic cyclohexa-1,3,5-triene[1] much like you cannot make (= synthesise) pseudoaromatic, biradicallic cyclobuta-1,3-diene. Hypothetical unsubstituted cyclohexa-1,3,5-triene will immediately give benzene, as this answer demonstrates.

The only way to actually generate nonaromatic cyclohexa-1,3,5-triene is to apply an intramolecular constraint that disallows the aromatization. Since cyclobuta-1,3-diene is the most obvious antiaromatic, planar system, that will attempt to always adopt a localised double bond structure, structure 1 below immediately suggests itself as a model system for the localised cyclotriene.

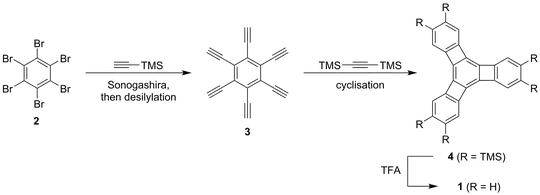

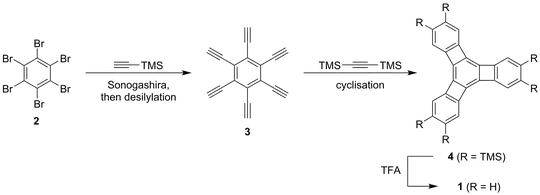

Scheme 1: Diercks’ and Vollhardt’s synthesis of a cyclohexa-1,3,5-triene system 1.

Indeed, that was the approach that Diercks and Vollhardt used to synthesise a model of cyclohexa-1,3,5-triene.[2] They report a crystal structure of 4 ($\ce{R}= \ce{TMS}$) wherein the alternating single and double bonds are clearly seen. The cyclobutyl sub-species adopts a cyclobutene-structure, meaning that the central cyclohexatriene ring’s double bonds are localised between the cyclobutane cores as indicated by the structure drawn. The outer benzyl rings are relatively aromatic (but not perfect hexagons).

Note and reference:

[1]: IUPAC nomenclature would allow systematically naming benzene as cyclohexa-1,3,5-triene. This is because IUPAC nomenclature assumes no knowledge of the chemistry of a given structure and requires names to be applicable ab initio and a priori. However, henceforth in this answer I shall make a distinction of (nonaromatic, localised, $D_\mathrm{3h}$-symmetric) cyclohexa-1,3,5-triene and (aromatic, $D_\mathrm{6h}$-symmetric) benzene.

[2]: R. Diercks, K. P. C. Vollhardt, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 3150. DOI: 10.1021/ja00271a080.