This is going to be a rehash of Oscar Lanzi's answer, but this point needs to be driven home, so I make no apologies.

"Special" electron configurations - fully-filled or half-filled subshells - are only a relatively minor factor in determining the stability of oxidation states. I've written about this before in a slightly different context, but IMO it would be well worth reading this, as the exact same principles operate in this case: Cr(II) and Mn(III) - their oxidizing and reducing properties?

What determines the "most stable oxidation state"? We can consider what happens when we increase the oxidation state of a metal: firstly, we need to pay ionisation energies to remove electrons from the metal. On the other hand, though, metal ions in higher oxidation states can form stronger bonds (e.g. lattice energy in ionic compounds, solvation energy in solution, or more covalent bonds in molecular compounds). The balance between these two factors therefore leads to a "best" oxidation state.

For example, sodium could hypothetically go up to Na(II) and form $\ce{NaCl2}$. Theoretically, this compound would have a significantly larger lattice energy than $\ce{NaCl}$. However, sodium's second ionisation energy is prohibitively large, which means that it stays put in the +1 oxidation state. On the other hand, magnesium's second ionisation energy is not prohibitively large, and therefore Mg preferentially forms $\ce{MgCl2}$ over $\ce{MgCl}$.

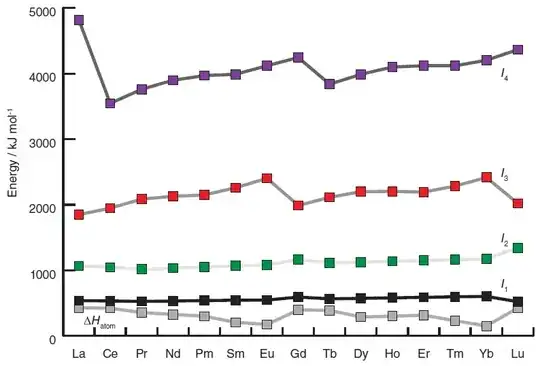

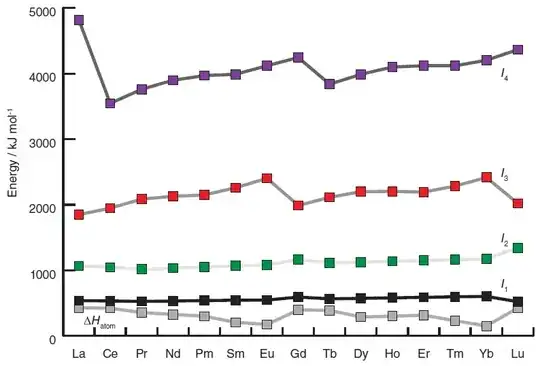

For all lanthanides, the first three ionisation energies are all fairly comparable. There is a graph here which shows the variation in the ionisation energies of the lanthanides, which I reproduce below.

(source: Inorganic Chemistry 6ed, Weller et al., p 630)

For all lanthanides, these three ionisation energies are easily compensated for by the extra lattice energy / solvation energy derived from a more highly charged ion. The fact that Eu(II) has a $\mathrm{f^7}$ configuration only serves to make its third IE marginally larger than that of Gd. This difference is sufficient to make Eu(II) an accessible oxidation state (cf. different electronic behaviour of EuO and GdO), but not sufficient to make it the most stable oxidation state.

Note that "most stable oxidation state" depends on the conditions, too, but I assume we are talking about aqueous solution.