I think the confusion arises because the hierarchy of "activity" as described in that figure exist in the context of an ontology that is closer to dynamical perception-action cycles than to the evolutionary information processing ontology typically used in cognitivist approaches.

The world is structured; it comprises discrete objectively existing entities, that is, objects. Subjects’ interaction with the world is also structured; it is organized around the objects. Objects have their “objective” meanings, determined by their relationship with other entities existing in the world (including the subject). In order to meet their needs, the subject has to reveal the objective meaning of the objects, at least partly, and act accordingly. — interaction-design.org, section 16.3.2.1

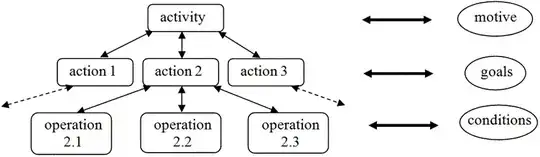

Activities are relations between subjects and objects (as in interests), so motives are objects. They exist in the sense that the grammar of a language exists, and are independent of any one person. Goals relate individual conscious processes (e.g., decision-making and planning) to these motives in order for the subject to concretely attain their object, and actions relate individual behavior to the goals.

However, these are only facets of the same continuously evolving system. There is therefore no way to describe an action without reference to an object and motive in an activity theoretical sense. In activity theory, all behavior is directed towards some motive as a matter of definition, and it is the motive which defines the activity. Motives entail goals, goals entail conditions, and reciprocally the other way around in a continuous dynamically evolving cycle.

The motive is the object that the subject ultimately needs to attain. For instance, in some cultural contexts people reaching a certain age need to learn how to drive a car (and get a driver’s license); it is a general prerequisite of being a fully functional member of society. Learning how to drive a car is an activity which is organized as a multi-layer system of sub-units directed at getting a driver’s license. Actions are conscious processes directed at goals which must be undertaken to fulfil the object. Goals can be decomposed into sub-goals, sub-sub-goals, and so forth. For instance, one may decide to enroll in a driving school, purchase instructional materials, make a schedule of theoretical lessons and practice sessions, etc. Actions are implemented through lower-level units of activity, called operations. Operations are routine processes providing an adjustment of an action to the ongoing situation. — interaction-design.org, section 16.3.2.2

A potentially helpful tool in understanding this ontology may be to notice the remarkable similarity with the Gibsonian concept of affordances as objectively existing perceptual entities (e.g., Chemero, 2003), only seen from a socio-cultural point of view. The relation between affordance and organism seems closely parallel to the relation between subject and object in activity theory.

Much like ecological psychologists need to define an ontology of objective affordances that define behavior for specific organisms within a specific environment before anything they say makes any sense, activity theorists need to define an ontology of objective motives for specific subjects within a specific socio-cultural context. Unlike EP, activity theory does not appear to provide a concrete way to identify objectively existing motives, nor exactly define the subjects or the socio-cultural context, so AT is ambiguous with respect to any individual case (e.g., a 'survival' motive or goal). See also what's comments about AT being implicitly situated within a Marxist context.

References

- Chemero, A. (2003). An outline of a theory of affordances. Ecological psychology, 15(2), 181-195.

(source: interaction-design.org)

(source: interaction-design.org)