OK, this is fun. I'm going to add my own thoughts and approximations, the first of which turns out to be identical to the one given by Massimo in this answer, and the one derived by Olli in this thread. I still include it here because its derivation is different. Then I'll show a better approximation, which has a maximum relative error of $0.002$ for $N=2$ (for which case we of course have an analytic solution for the exact cut-off frequency: $\omega_c=\pi/2$), and for which the relative error is smaller than $1.2\cdot 10^{-4}$ for $N\ge 10$.

It is well known, and was shown by Olli and Robert in their answers, that the real-valued amplitude function of a length $N$ moving average filter is given by

$$H_N(\omega)=\frac{\sin\left(\frac{N\omega}{2}\right)}{N\sin\left(\frac{\omega}{2}\right)}\tag{1}$$

The $3$ dB cut-off frequency $\omega_c$ satisfies

$$H_N(\omega_c)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\tag{2}$$

As far as I know there is no reasonably simple analytic solution to Eq. $(2)$. The key to the approximations presented here is - not surprisingly - a Taylor approximation. The difference between the Taylor series used in Robert's answer is that I do not separately approximate the sine functions (or their squared values as in Robert's answers), but I directly approximate the complete amplitude function given in $(1)$. Approximating $\sin(N\omega/2)$ (or its squared value) will result in larger errors than when the complete function is approximated, because the argument $N\omega/2$ never approaches zero, even for large values of $N$. Approximating only the denominator $\sin(\omega/2)$ (or its squared value) is OK, because its argument $\omega=\omega_c$ does approach zero for large $N$. Anyway, I will use neither of the two approximations, but I will use the Taylor series of $H_N(\omega)$. For simpler notation I'll use $x=\omega/2$ and $F_N(x)=H_N(\omega)$. The Taylor series of $F_N(x)$ around $x_0=0$ is given by

$$F_N(x)\approx 1-\frac{N^2-1}{6}x^2+\frac{3N^4-10N^2+7}{360}x^4\tag{3}$$

For large values of $N$, this approximation is legitimate because the cut-off frequency $\omega_c$ tends to small values.

For the first approximation I only use the first two terms in $(3)$:

$$1-\frac{N^2-1}{6}x_c^2=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\tag{4}$$

Solving $(4)$ gives a first approximate solution:

$$\omega_{c1}=2x_c=\frac{2\sqrt{6(1-\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}})}}{\sqrt{N^2-1}}=\frac{2.65130859228473}{\sqrt{N^2-1}}\tag{5}$$

The problem with this solution is that it is biased, which means that its error doesn't converge to zero for large $N$. However, it turns out that by a simple scaling of $(5)$, this biased can be removed. For zero bias we require

$$\lim_{N\rightarrow \infty}H_N(\omega_{c1}(N))=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\tag{6}$$

where I used the notation $\omega_{c1}(N)$ to emphasize its dependence on $N$. Solving $(6)$ with the general expression

$$\omega_{c1}=\frac{a}{\sqrt{N^2-1}}\tag{7}$$

leads us to the equation

$$\frac{\sin(a/2)}{a/2}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\tag{8}$$

which must be solved numerically for the by-now-famous solution

$$a=2.78311475650302\tag{9}$$

The approximation $(7)$ with $a$ given by $(9)$ is identical to Massimo's formula (you have to divide by $2\pi$ to get his magic constant), and it's also the same as the one derived by Olli in a different way in this thread. We see that a Taylor approximation gave us the correct form of the equation, but the constant had to be determined by a limit process in order to get a formula with zero bias. For most practical purposes, this formula is sufficiently accurate with a maximum relative error of $6.9\cdot 10^{-4}$ for $N\ge 10$.

Using all terms in the approximation $(3)$ will give us an even better approximation. The process is exactly the same as before: we set the Taylor approximation of $F_N(x)$ equal to $1/\sqrt{2}$ and solve for $x_c$ (there are only even powers of $x$, so we only need to solve a quadratic equation). This gives us the following formula:

$$\omega_{c2}(N)=2\sqrt{6}\sqrt{\frac{5(N^2-1)-\sqrt{5}\sqrt{(3\sqrt{2}-1)N^4+10(1-\sqrt{2})N^2+7\sqrt{2}-9}}{3N^4-10N^2+7}}\tag{10}$$

Note that of the four solutions of the quartic equation, we need to choose the smaller of the two positive ones, because that's the value where the Taylor series closely approximates $F_N(x)$. The other positive solution is an artefact in a range where the Taylor series diverges from $F_N(x)$. The approximation $(10)$ has the same small problem as the first version of the previous approximation given by $(5)$ in that it has a small bias. This bias can be removed in exactly the same way as before by considering the limit $(6)$, this time with $\omega_{c2}(N)$. My final approximation based on $(10)$ but with zero bias is given by

$$\omega_{c3}(N)=b\omega_{c2}(N)\tag{11}$$

where $b$ can also be obtained by solving an equation similar to $(8)$. It can actually be written in terms of $a$ given by $(9)$:

$$b=\frac{a}{2\sqrt{2}\sqrt{5-\sqrt{5(3\sqrt{2}-1)}}}=0.997314251642175\tag{12}$$

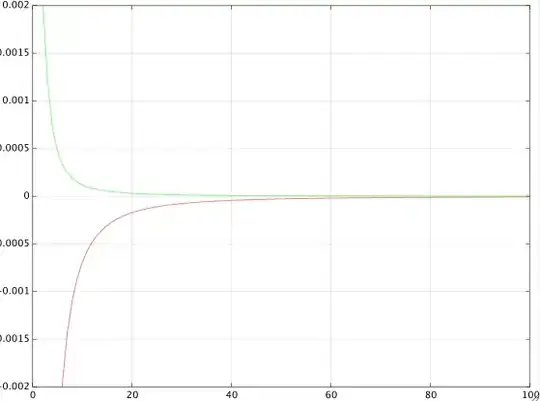

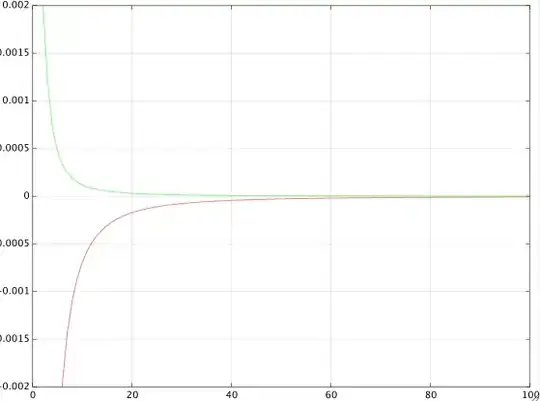

I computed the exact values of $\omega_c$ numerically for $N$ in the range $[2,100]$, so I could compute the relative error

$$\epsilon_i=\frac{\omega_c-\omega_{ci}}{\omega_c}\tag{13}$$

which allows the comparison of different approximations $\omega_{ci}$. I'll only discuss the approximations with zero bias: $\omega_{c1}$ given by $(7)$ with $a$ given by $(9)$, and $\omega_{c3}$ given by $(11)$ (and $(10)$), with $b$ given by $(12)$. The figure below shows the relative errors as defined by $(13)$ as a function of $N$. The red curve is the relative error of approximation $(7)$, and the green curve is the error of approximation $(11)$. Both approximation have zero bias (they converge to the exact values for large $N$), but the green curve converges significantly faster.

The zero-bias formulas shown above are decent approximations to the actual cut-off frequencies, but the better one (formulas $(10,11,12)$) is very awkward. Olli had the great idea to tweak the denominator constant in the simple formula $(7)$. As long as we use the optimal value of $a$ given by $(9)$, we can change the denominator constant without losing the zero-bias property. So we get a new formula

$$\omega_{c4}(N)=\frac{a}{\sqrt{N^2-c}}\tag{14}$$

with a constant $c$ to be optimized. If I understood correctly, Olli based his optimization of $c$ on the error value for $N=2$. However, I think that the value $N=2$ is not very relevant because for $N=2$, $\omega_c$ can be computed analytically: $\omega_c(2)=\pi/2$. So we don't necessarily need to optimize formula $(14)$ for the case $N=2$ if it comes at the expense of the approximation at larger values of $N$. I optimized the constant $c$ in $(14)$ in the following way. If $\omega_c(N)$ are the exact cut-off frequencies for a given set of filter lengths $N$, we have an overdetermined system of equations:

$$\omega_c(N)\stackrel{!}{=}\frac{a}{\sqrt{N^2-c}},\qquad N=2,3,\ldots\tag{15}$$

where we can choose any reasonable set of values for $N$. Rearranging $(15)$ gives another set of equations, this time linear in the unknown $c$:

$$N^2-c\stackrel{!}{=}\frac{a^2}{\omega_c^2(N)}\tag{16}$$

The optimal least squares solution of $(16)$ is

$$c_0=\frac{1}{L}\sum_N\left(N^2-\frac{a^2}{\omega_c(N)}\right)\tag{17}$$

where $L$ is the number of different values for $N$ used in the sum. If you use all integer values of $N$ in the range $[2,100]$ you get

$$c_0=0.863031932778066\tag{18}$$

which is close to Olli's value, but which gives an even better approximation for all $N\ge 3$. I added the error values to this table, column f).

In his answer, Robert was wondering why he must discard the second (larger) positive solution for $\omega_c$ when using a fourth order Taylor series for $\sin^2(x)$. The figure below shows the reason. The original squared amplitude function is shown in blue (for $N=10$). The 3dB line is in red. The green function is the Taylor approximation, which crosses the red line twice. These are the two positive solutions for $\omega_c$. Since the function is even, we also get the same two solutions with negative signs, which makes it four, as should be the case for a fourth order polynomial. However, it is obvious that the larger of the two positive solutions is an artefact due to the divergence of the Taylor approximation for larger arguments. So it is only the smaller solution which makes sense, the other one doesn't.

which has the limit, for large $N$, of $$ \omega_0 \approx \frac{2.88}{N} $$.

– robert bristow-johnson Jan 13 '16 at 05:43