We can determine the total rms phase noise by integrating the single-sided power spectral density $S_{\phi}(f)$ after being modified by the high pass function of the carrier tracking loop (which will remove the very slow varying changes in phase, which is its purpose) out to the modulated signal bandwidth), and then taking the square root of this result (since the integration will be the total power relative to the channel or "carrier"). $S_{\phi}(f)$ is twice the double-sided power spectral density $\mathscr{L}_{\phi}(f)$ which is typically what is used to represent phase noise. Without the specific carrier tracking transfer function, we can make a reasonable approximation using the carrier tracking loop bandwidth as follows:

$$\phi_{rms} = \sqrt{2\int_{B_1}^{B_2}\mathscr{L}_\phi(f)df}$$

Where:

$B_1$: Carrier tracking loop bandwidth

$B_2$: Single-sided modulated signal bandwidth

The relationship between rms phase noise and SNR, when phase noise is the limiting factor is (and under small angle approximations which hold in most practical examples with Local Oscillator phase noise):

$$ SNR = 20Log_{10}(\phi_{rms})$$

The relationship between EVM and SNR depends on the specific definition for EVM used as further detailed here:

How to calculate EVM in %age of an Equalized Constellation in 16QAM?

I explain the interaction and consideration of oscillator phase noise and the recovery loop further using the graphics below depicting two slices of phase noise before and after the effects of the carrier tracking loop:

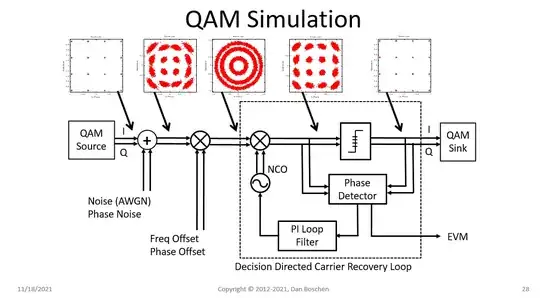

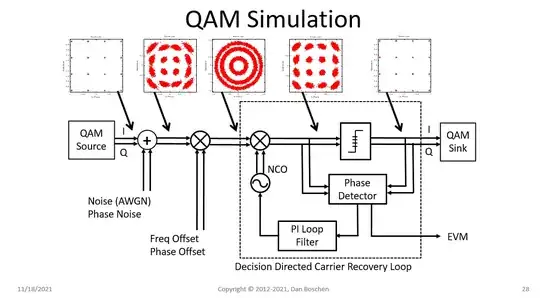

Here is a depiction of a QAM simulation I have done where we see the effects of phase noise in the constellation before and after the carrier tracking loop. Notice the reduced phase noise in the constellation just prior to the final decision, which has been "tracked" out along with the carrier offset, as expected.