I came across the concept of analog and digital signals in my data communication course. We studied that analog signals are continuous signals and teacher presented a diagram like the sine wave and that digital signals are discrete; He showed a diagram of digital signal too. I am not an electronics student but I would like to know how these signals are generated and what is meant by continuous and discrete signals in reality. Please tell me something more about these signals.

-

Digital in its simplest form is either ON or OFF and relates directly to binary data of 1 or 0. Analogue is like sound and gets translated in many forms-the simplest being very loud = 1 and very soft = 0; Modems send sound to each other and they transalte complex noises into BITs , hence the better the frequency eg.Broadband the more sound we can put in to change to Digital. But it is more complex than that... – Piotr Kula Oct 10 '11 at 22:49

8 Answers

Often, people will think that any signal that switches between two voltages is "digital". This is not correct.

"Digital" means that the signal is carrying information in the form of discrete symbols. As long as the symbols are received correctly, no information is ever lost in transmitting a digital signal.

Analog signals are always degraded by transmission, even if the degradation is very small.

- PCM signals are digital, and consist of switching between two voltages. As long as you receive the series of 1s and 0s in order, no information is lost.

- PWM signals are analog, and consist of switching between two voltages. The exact timing of the pulses carries information, so if there's any variation in timing from noise, etc. the signal is corrupted.

- FSK signals are digital, and consist of sine waves. As long as the frequency of each bit is recovered, no information is lost.

- 28,734

- 24

- 119

- 184

[Normally I wouldn't answer a 3.5 year old question, but none of the existing answers actually answer the submitter's question.]

As I understand it, the question is about how analog and digital (continuous and discrete) signals are generated physically, and what their physical differences are. The simplest answer to this is that all physical signals are analog. The real difference is in how we interpret them. To understand this, let's look at a non-electrical example of a discrete system -- language.

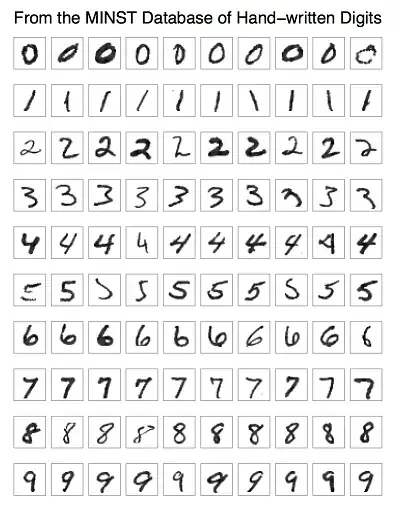

This image (source) shows handwritten numbers:

Are these five symbols identical? No. But they're all the number 3. Why? Because we've agreed that in certain contexts (writing numbers), we will use a small number of symbols (numerals), and we will interpret everything we see as being one of those symbols. Thus, even though all hundred symbols in this image are different, we say that there are only ten numerals in it:

This means we've limited the amount of information that a symbol can carry, which is called quantization. We've also decided to separate the symbols on the page, which is called discretization or sampling. (In electronics, symbols are usually separated in time, not space.) Doing all this has some big advantages:

- Error tolerance: If a symbol is smudged or faded, you can usually tell what it is.

- Copying: A copy of a symbol carries exactly the same information as the original symbol.

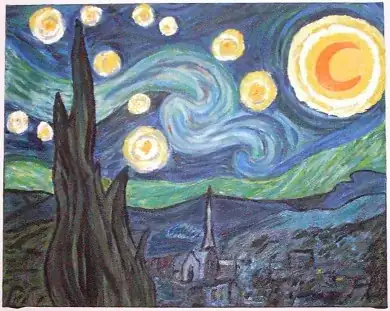

Now let's consider an analog "system" -- painting. Here are two paintings. The first is Vincent van Gogh's "Starry Night". The second is a copy by another artist.

Although these paintings show the same subject in a similar way, we normally don't say they're the same. Why? Again, the answer is context. When looking at art, we care about all the information in the image. The second image is a copy of the first, but it's not an identical copy, and it does not carry the same information as the original. Making a copy of the copy would cause even more information to be lost or altered.

So why use analog signals at all? Because the world is analog. Our bodies and our senses are analog. What we hear and see is analog. Any information that gets into our brains must do so through an analog medium.

Analog electronic systems work by acting like the information they carry. Think of the grooves on a record -- they're shaped like the sound waves. "Analog" and "analogy" come from a Greek word that means "proportionate". To make an analog electronic system, all you have to do is generate a voltage or current that's proportional to some other physical quantity -- pressure (sound), light intensity (video), position (user input), etc. This is simple to do, which is why it was done first. It's hard to do well, which is where digital comes in.

In simple digital electronic systems, there are only two symbols -- 1 and 0. Physically, these are voltages. For example, we could say that any voltage less than 2.5 volts is a 0, and any voltage greater than 2.5 volts is a 1. Then we need a circuit that implements quantization. For example, a circuit could output 5 volts if the input is anywhere in the 1 range, and 0 volts if the input is anywhere in the 0 range. That's basically a high-gain amplifier. (We can use variants of this circuit to implement Boolean algebra.) Finally, we need to implement sampling. This is done with the help of a special signal called a clock, which is usually a square wave, and a special circuit called a latch or a flip-flop.

With these building blocks, we can copy and process digital data in many ways. The downside is that because each symbol carries so little information, it takes a lot of symbols (and circuitry) to get any useful work done. In the last few decades, integrated circuit technology has allowed exponentially more circuitry to fit into the same space for the same cost. With enough bits, a fast enough sample rate, and enough circuitry, it's possible for digital systems to equal or exceed the amount of information in analog signals. At that point, digital's advantages begin to dominate and we end up with the world we have today.

Since the question mentioned communications, I should point out that digital communications systems often use more than two symbols so they can fit more data into the same bandwidth.

- 21,959

- 4

- 51

- 91

Update:

Continuous signal: Suppose you are hearing a siren in normal way, we can say it is continuous. That is pure analog.

Discrete signal: When hearing the above, if you close and open both of your ears continuously using your fingers, that is discrete signal. Here you are skipping, in positive way you are collecting some samples of the signal. This signal is discrete, but not digital. Here if you close and open your ears with a higher speed, you can understand the increase or decrees of alarm volume. ie, you can get the analog information with a minimum distortion.

Digital Signal: You write each sampled volume of the alarm to a paper, and represent it in digital form. This is called Digital signal.

Analog signal is continuous, while the digital signal is discrete. The discrete nature is achieved by skipping some portion of the analog signal and representing the resultant signal by means of symbols.

When we consider both an analog and digital signals which carry same information(Real world data), we can say, the analog signal carry the most accurate and original information.

The world is of analog data, and we convert it to digital because of some beautiful qualities of digital signal. You can understand more from any book on digital electronics or digital communication.

- 1,172

- 1

- 13

- 17

Continuous signals can take on any value in a given interval. For instance, the function sin(x) is defined for all x and can take on any value between 1 and -1.

In contrast, discrete signals are sequences. The function sin(x) in its discrete form can be written as

$$sin(2\pi f n + \phi)$$

where n is an integer. In other words, the above form is only defined at n=0,1,2,3...

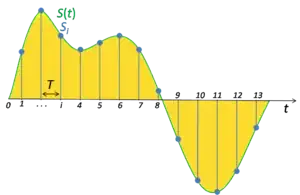

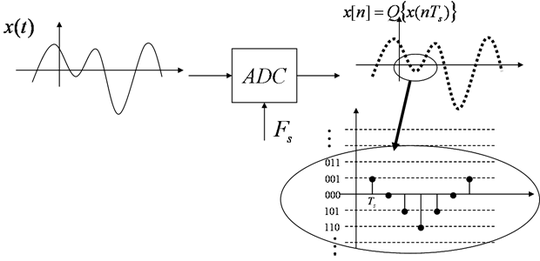

Continuos signals are measured by sensors (there are sensors which spit out digital signals. They will have a DAC built-in and save you the trouble of converting them) and then manipulated by analogue circuits, like opamps and such. However, if you want the signal to be processed by a computer or a microcontroller, you need to digitize the signal. Here's a figure from wikipedia illustrating this:

Note that in the above figure, samples are taken every fixed internal (1,2,3,4... and so on). It's important to understand that this is leading us to an approximation of the original signal - after all, how we know what the value of the continuos signal was between sample 8 and 9? Can you see that if the intervals between each sample is short, it will lead us to a much better approximation and if the interval is large, we may not even be able to tell what the original signal looked like! Try and think about this for a minute. Here's an example:

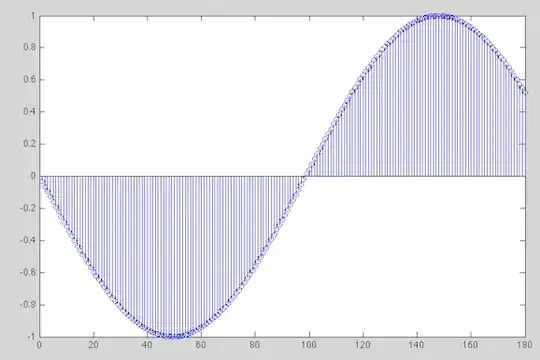

Can you guess what this signal is? If you guessed its a sinusoid, you're right. But notice that it's not really a very good approximation. Here's another example - the shape of the signal is much more easy to see when the interval is short, isn't it? This is a much better approximation than the previous example.

So how fast should you sample your continous signal? According to Nyquest, you should sample your waveform at more than twice its frequency (if your signal has multiple frequencies, you should sample more than twice as fast as the highest frequency in your system).

One important thing to realize is the difference between discrete and digital. The value of a sample in a discrete signal can be any number. On the other hand, a digital signal is signal that can only have discrete values e.g. 1,2,3... etc If it's a 8-bit signal, the maximum value is only 255.

To acquire a digital signal, you must quantize your discrete-time signal. As your question didn't ask for it, I won't go into any further.

So, to sum it up, I'll leave you with an example that illustrates where the signals might come from and why they're digitized. Let's assume you want to use a microphone to record something. Let's also assume that the frequency of your target is, say, 1kHz. Your microphone will provide you with a continuos voltage that represents your recording. If the sound you recorded was sinusoidal, than your voltage will be sinusoidal.

But you also want to use this signal for some of processing. We don't care what sort of processing you wanna do, we just know you want to do it in a microcontroller or a computer. As mentioned before, to feed this information into a computer you must first digitize the signal. You can do this via a device called Analogue To Digital Converter (ADC). This device will take an continuos waveform and spit out a digitized version of it. The digitized form is then fed to a computer which does its thing and spits out the output - which is also, of course, digital. Now, in order to listen to this recording, you need to convert the digital signal to an analogue (continuos) one using a Digital to Analogue Converter (DAC). The analogue version is amplified and than played through headphones or a speaker. Hope this helps.

- 5,369

- 12

- 60

- 94

While there are great answers here, I feel that one major thing is not talked about enough. Saad mentioned that the discrete signals are sequences and the shorter the time is, better representation of original signal we get and it is here that we touch the, in my opinion at least, most important difference between continuous and discrete signals:

During the time T (on Saad's first diagram) which is the time between two samples in a discrete signal there is actually no information about the signal. This is important because of many problems which arise in signal processing you'll probably hear about later. Since we usually get discrete signals by sampling continuous signals, we have absolutely no idea what's going on with the continuous signal between two samples of the discrete signal.

For example let's look at this image from Wikipedia:

Let's say that the red signal is our continuous signal and that the black points are samples of our discrete signal. If you "connect the dots", that is to say try to interpolate the discrete signal, you'll get the blue signal which is very different from the red signal. Yes, the sampling theorem has been mentioned, but in some cases in real world, you won't know what range of input frequencies to expect and you may not have powerful enough laboratory equipment to try to record the actual waveform of the signal.

So the bottom line is: Discrete signals only provide data which they actually provide! While this tautology may look obvious and not worth mentioning, people tend to assume that discrete signals are actually sampled at the correct frequency and that they provide a representation of original signal of sufficiently high fidelity. This is not always the case!

- 23,431

- 27

- 112

- 189

\$x(t)\$ is an analogue signal, continuous in time and in voltage. To convert it to a digital signal you first have to sample it, which means that you take the value of the signal at a certain interval, for instance once every ms for a 1ksps (Kilo Sample Per Second) signal. The voltage range is still continuous. The actual ADC (Analogue to Digital Conversion) measures the voltage at each sample as a numeric value, we say the signal is quantized. Since it's now represented as a numeric value, it can't take any value like it could in a continuous range. The resolution determines how many values the quantized signal can take. An 8-bit signal can take 256 distinct values. If your input signal range is 2.56V each next discrete value will be 10mV higher than the previous one. So you'll have a 50mV value, and a 60mV value, but nothing in between. This is often shown in a diagram as a staircased signal, or with discrete dot, like in the above diagram. In any case the fluent line has gone.

Digital means it's being represented by a sequence of numbers, one for each consecutive sample. This representation can be a close approximation of the original signal if you sample fast enough at a high resolution, for instance 20 bit, but if you look close you still see the staircase steps.

A binary signal, just 0s and 1s, is just one possible digital signal, namely with 1 bit resolution, though it's often represented as the digital signal. Digital signals can take a multitude of values.

- 145,832

- 21

- 457

- 668

You have to distinguish between different worlds.

The:

- Analog world and

- Digital world

However, the imagination is, that the:

- Analog world, is (mathematically seen) a continuum. That means that it can't be counted

- Digital world, is a (mathematically seen) NOT a continuum. That means that it can be counted.

By the way, digital doesn't mean 0 or 1 at all!

Even the symbols 0 to 9 are digital !

You could even build a decimal computer who can store four digits which are going from 0 to 9. So you could represent 0000-9999, 10^4 = 10.000 values. So it's finite and therefore digital. But no one is doing that because binary is easier to build ^^

Concerning the signal stuff it's using those two worlds, described above. If you're talking for example to somebody it's a analog signal. You can change your voice in endless ways ! But you can convert your voice with an AD-Converter to a binary signal.

- 419

- 1

- 8

- 15

Whether a signal is analog or digital depends on what the recipient does with it. Further, signals should be regarded as having two aspects--level and time--each of which may be either continuous or discrete. There are thus four combinations of continuous/discrete to be considered.

A signal is considered a discrete-level signal if the devices that are observe at any given time it do nothing but identify whether it is above or below various levels; it is a continuous-level signal if the exact level of the signal within the device's operational range will be significant in determining its output.

A signal is considered a discrete-time signal if there is a process that examines the state of the signal at certain particular moments, and ignores the state of that signal at other times.

Some kinds of circuit like switched-capacitor filters sample the input signal at discrete times and ignore it at other times, but have an output which depends in analog function upon the input. Other kinds of circuit like an FM-radio receiver may be looking for signal edges continuously, rather than only at discrete times, but care nothing about the level of the signal at any moment beyond the question of whether it's low or high. Many common situations involving feeding signals to processors, however, entail quantizing both level and time.

- 46,736

- 3

- 87

- 148