I bought a 1990's steel mountain bike a few weeks ago and I have some concerns about the design of the rear dropout, pictured here:

It seems to me that an ideal dropout design would redirect upward force from the wheel axle toward the ends of the seat and chain stays. The axle mount should be positioned closer toward the center of the bike, and below the chain stays so as to distribute upward force between them. Here's a diagram showing how I expect force to be transferred to the frame by the wheel axle when the bike lands from a jump:

For maximum load-bearing capacity, I would expect the dropout to redirect the force of impact perpendicularly to the tip of the seat stay. However, here the angle is about half that, so half the force is applied to the seat stay as torsion force instead of compression force. This isn't ideal because the soldered joint isn't as strong as regular steel, so it becomes a stress point when torque is applied. While that's still the case when compression force is applied, the joint is less vulnerable to compression force due to technical reasons I can't explain.

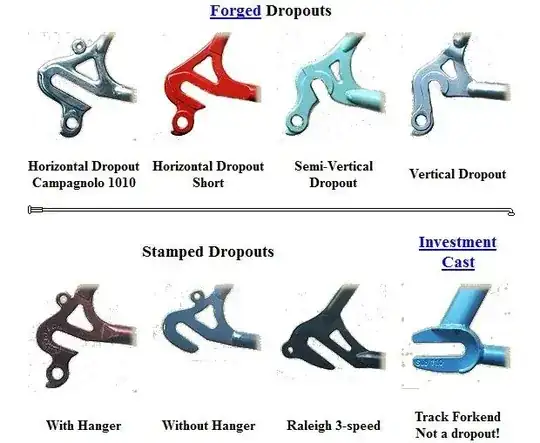

Almost every other dropout design I've came across at least tries to redirect the force so that it meets the seat stay directly. Here is an image with some examples of other rear dropouts:

In these examples, upward force is always directed toward the base of the seat stay, whereas the chain stay of my bike extends in a way that pushes the axle mount further to the rear, off center from the truss that connects the chain stay, seat stay, and axle. I think this means that most of the force is transferred perpendicularly to the upper truss member, which connects to the seat stay at an angle and exerts perpendicular force that's not balanced out by opposing force from the lower truss member.

In the examples, while some axle mounts are positioned further away from the stays than others, the dropouts in those cases are long and flexible enough to provide structural support that can absorb some force of impact. In my bike, the dropout is both off center and not long enough to provide structural support by itself, so I think most of the force is transferred directly to the seat stay at an angle.

I don't think the chain stay handles much load either because it sits slightly below the axle mount point and so doesn't receive much compression force.

Finally, the dropout functions to securely join the seat stay with the chain stay, but the lower truss member doesn't form a very smooth curve between the stays, creating a stress point at the chain stay.

Is my analysis correct? Does any of this have a significant impact on the stability and strength of the bicycle?