This question was inspired by this Quora question.

I'm sure lots of you are familiar with the fact that we have many different representations of $\pi$, things like $$ \begin{align} \pi & = \sqrt{6\zeta(2)} \\ & = \frac{4}{1 + \frac{1^2}{3 + \frac{2^2}{5 + \frac{3^2}{7 + \frac{4^2}{9 + \ddots}}}}} \\ & = 2\frac{2}{\sqrt{2}}\frac{2}{\sqrt{2 + \sqrt{2}}}\frac{2}{\sqrt{2+\sqrt{2+\sqrt{2}}}}\cdots \\ & = \frac{9801}{2\sqrt{2}}\left(\sum_{k=0}^\infty{\frac{(4k)!(1103 + 26390k)}{k!^4(396^{4k})}}\right)^{-1} \\ & = \frac{640320^{3/2}}{12}\left(\sum_{k=0}^\infty{\frac{(6k)!(13591409 + 545140134k)}{(3k)!(k!)^3(-640320)^{3k}}}\right)^{-1} \\ & = \lim_{r\to\infty}\frac{1}{r^2}\sum_{x=-r}^r\sum_{y=-r}^r{\left[\sqrt{x^2+y^2}\le r\right]} \\ & = \frac{2}{\operatorname{Li}_2(3-\sqrt{8})-\operatorname{Li}_2(\sqrt{8}-3)}\int_0^1{\frac{\arctan^2x}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}\text{d}x} \\ & = \left(\Gamma\left(\frac34\right)\sum_{n\in\Bbb{Z}}e^{-\pi n^2}\right)^4 \\ & = \cdots \end{align} $$ and the list continues indefinitely.

All of these, obviously, have their respective individual proofs. Some proofs rely on one another, others stem from thinking about $\pi$ in a fundamentally new way (such as 6th identity, which is basically a mathematical encoding of the number of points inside the unit circle in a square region), and others are results obtained in reverse (such as the last two identities).

What interests me is not how each one of these proofs is carried out independently, it's how they are associated that interests me. My question is this; how "independent" are two proofs? Another way of stating this problem might be, for any two identities with different proofs (i.e. any two proofs of a formula for $\pi$), can you go directly from one identity to the other without passing through the original identity?

Let me see if I can describe this better. I'm sorry I don't have the background on proof theory or logic theory or things like that necessary to make the semantics of my question well defined, but I'll do my best to give a notion of what "independence" means in regards to two proofs.

Say we wanted to show for example, that $$ 2\frac{2}{\sqrt{2}}\frac{2}{\sqrt{2 + \sqrt{2}}}\frac{2}{\sqrt{2+\sqrt{2+\sqrt{2}}}}\cdots = \frac{2}{\operatorname{Li}_2(3-\sqrt{8})-\operatorname{Li}_2(\sqrt{8}-3)}\int_0^1{\frac{\arctan^2x}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}\text{d}x} $$ Would there be a way of proving that this is true without just proving that both sides are equal to $\pi$?

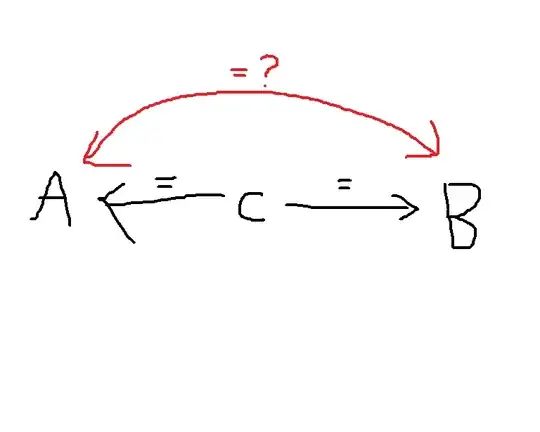

So in general, say we have two formulas $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ that both evaluate to the same constant $c$. That is $$ \mathbf{A} = c, \qquad \mathbf{B} = c $$ and thus $$ \mathbf{A} = \mathbf{B} $$ because $c = c$. If we weren't allowed to use the fact that both $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ are equal to $c$, is there always a way to prove $\mathbf{A} = \mathbf{B}$? In my head it looks like this:

Can we always find the red line that proves $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ are equal without going through any of the black lines?

In addition, if this question isn't very well understood yet, are there any interesting advances in proof theory or other disciplines that have gotten us any closer? What literature is there on this topic?