Given the Euclidean coordinates of two points (p1, p2) and (q1, q2) in the unit circle, how do I construct the Euclidean circle x^2 + y^2 + fx + gy+1 representing the hyperbolic d-line on the poincare disk containing these points?

3 Answers

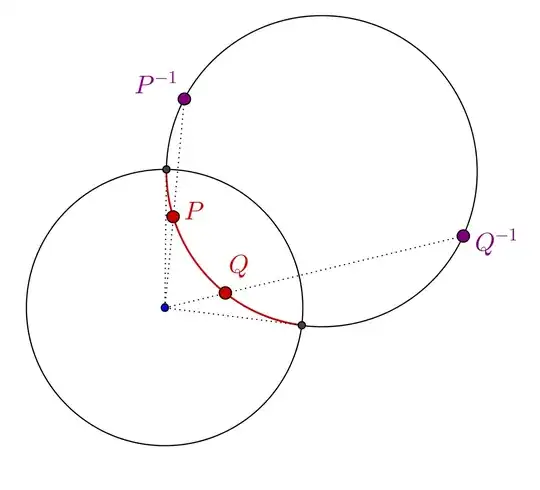

A circle orthogonal to the unit circle through the points $P,Q$ must go through $P^{-1}$ and $Q^{-1}$, too, where $P^{-1},Q^{-1}$ are the circular inverses of $P$ and $Q$ with respect to the unit circle. That simply follows from the Tangent-Secant theorem.

Hence the hyperbolic line through $P=(x_1,y_1)$ and $Q=(x_2,y_2)$ is just an arc of the circle through $P,Q$ and $$P^{-1}=\left(\frac{x_1}{x_1^2+y_1^2},\frac{y_1}{x_1^2+y_1^2}\right).$$

- 353,855

-

1Something is wrong with our textbooks , let's show the simplicity of it all and not hide behind smoke screens of complexity. – nilo de roock Jun 16 '15 at 09:09

-

Is there something wrong with your formula about $P^{-1}$? in your formula $P^{-1}$ is purely determined by P, However the position of $P^{-1}$ should depend on both P and Q – Long Oct 27 '19 at 19:28

-

2No, the inverse of a point (with respect to a circle) is a function of that point, it does not depend on something else. – Jack D'Aurizio Oct 27 '19 at 20:14

-

@Long The information that Q gives is encoded in the fact that the circle has to pass through Q, if that is what your doubt was about. P^-1 adds no essential information to the problem, and neither would Q^-1. – Zokalyx Dec 19 '20 at 15:55

-

This is very nice. If P lies on the unit circle though, you'll have to use Q^-1 as the third point. And if P and Q lie on the unit circle, you can't get a third point this way, and will have to do something else. – user214962 Feb 05 '21 at 22:49

The centres of circles that go through point $(p1, p2) $ and that are orthogonal to the unit circle

are on the line:

$$ y = \frac{p_1^2+ p_2^2 +1 -2 p_1 x }{2 p_2} $$

so the point you are looking for is on two such lines

the rest is algebra

Good luck

- 6,582

Let $P$ and $Q$ be the points. Tee "line" you want is a circle $C$ containing $P$ and $Q$ and perpendicular to the unit circle, meeting it at points $A$ and $B$. (Draw that picture for yourself, please).

If $P$ and $Q$ lie on a diameter of the unit circle (i.e., if $PQ$ contains the origin), then the solution is the (euclidean) line $PQ$. Else:

Draw the perp. bisector of $P$ and $Q$. The center of the circle $C$ must lie on this bisector. For any point $X$ of the bisector that's outside the unit circle, you can draw a tangent to the circle through $X$; the length of this tangent varies with $X$. When this length is also the length of $XB$, say, then $X$ must be the center of the circle $C$ that you're seeking.

Since all the stuff in the preceding paragraph can be converted to expressions linear in the coordinates of $P$ and $Q$ (for the bisector) or quadratic in $s$, the distance of $X$ from the midpoint $(P+Q)/2$, the problem now reduces to solving a quadratic in $s$. I'll leave that to you. (There are two solutions to the quadratic in general, but only one represents the center of circle $C$, so there may be a "solve and test" phase to this solution.

- 93,729

-

'Thanks, but there must be a reference to a map from two points to a circle readily available somewhere. – nilo de roock Jun 12 '15 at 10:17

-

I see. Your question wasn't "how do I construct this?" but "What's a formula for the coordinates of the point?" I'm sure you're correct, and if you'd asked that, I wouldn't have bothered answering. – John Hughes Jun 12 '15 at 10:22

-

-

Because I don't know. I shared what I did know. I suspect that working out the algebra from my description above might give some insight (or it might not!), but I don't care enough about the hyperbolic plane to do it. You, who apparently do care, might want to make the investment, though. An alternative approach: invert the unit circle about $(1,0)$ to get a line; now seek a circle through the two transformed points $P'$, $Q'$ that meets this line perpendicularly...its center is on the line. You can find the intersections, $A'$, $B'$ transform back, and solve the simpler problem. – John Hughes Jun 12 '15 at 11:32

-