This comes from the regularity of $u$. For $u\in H^2$,

$$-\Delta u=f\quad\text{in}\quad\mathcal{D}'(\Lambda)\tag{#}$$

means

$$\int_\Lambda(-\Delta u)\varphi\;\mathrm{d}\lambda=\int_\Lambda f\varphi\;\mathrm{d}\lambda\quad\forall\ \varphi\in\mathcal{D}(\Lambda)$$

which implies

$$-\Delta u=f\quad\text{a.e.}\tag{$*$}$$

by the du Bois-Reymond Lemma. Multiplying $(*)$ by $v\in H^1(\Lambda)$ and integrating over $\Lambda$ you get the result (without any further regularity on $\Lambda$).

Edit

Let $\Lambda\subset\mathbb{R}^d$ be open and $f,u\in L^1 _{\text{loc}}(\Lambda)$. The distributions $f$, $u$ and $\Delta u$ are defined by

$$\langle f,\varphi\rangle=\int_\Lambda f\varphi\;\mathrm{d}\lambda,\quad \langle u,\varphi\rangle=\int_\Lambda u\varphi\;\mathrm{d}\lambda,\quad \langle\Delta u,\varphi\rangle=\langle u,\Delta\varphi\rangle=\int_\Lambda u\Delta \varphi\;\mathrm{d}\lambda,\quad\varphi\in\mathcal{D}(\Lambda).$$

Assume that $u,f\in L^1_{\text{loc}}(\Lambda)$ and $-\Delta u=f$ in $\mathcal{D}'(\Lambda)$. Then

$$-\int_\Lambda u\Delta \varphi\;\mathrm{d}\lambda=\int_\Lambda f \varphi\;\mathrm{d}\lambda.$$

If, additionally, $u\in H^2(\Lambda)$ and $\Lambda$ is bounded with Lipschitz boundary, then (Corollary 3.46 here)

$$\int_\Lambda (-\Delta u) \varphi\;\mathrm{d}\lambda=-\int_\Lambda u\Delta \varphi\;\mathrm{d}\lambda=\int_\Lambda f \varphi\;\mathrm{d}\lambda.$$

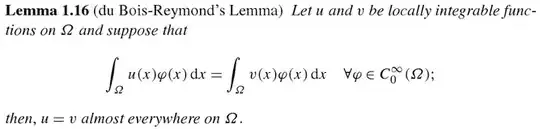

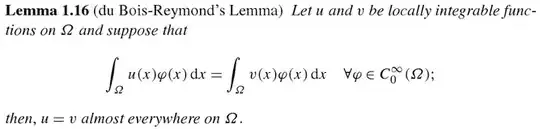

Therefore by the Du Bois Reymond Lemma (Lema 1.16 here)

$$-\Delta u=f\quad\text{a.e.}$$

Conclusion: $(\#)$ implies that

$$\int_\Lambda(-\Delta u)v\;\mathrm{d}\lambda=\int_\Lambda fv$$

for all $v\in H^1(\Lambda)$ provided that $\Lambda$ is a bounded open set with Lipschitz boundary and $u\in H^2(\Lambda)$.

Edit 2

Print of the third link: