Actually I get the exact opposite as the text does.

As $\gcd(a,b,c) = 1$ and $\gcd(a,b) = g$ we know $\gcd(g,c) = 1$

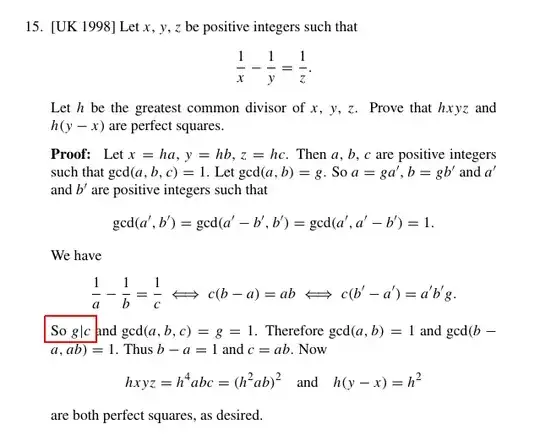

So we have $c(b'-a') = a'b'g$ so $g|(b'-a')$ Furthermore we know $\gcd(a'-b',a') = \gcd(a'-b',b') = 1$ so $a'b'|c$.

So we have $\frac {c}{a'b'}(b'- a') = g$. But $\gcd(g,c) =1$ so $\frac{c}{a'b'} = 1$ so $g = b'-a'$ (but that's not relevant) and $c = a'b'$ (and that is relevant).

So $hxyz = h^4abc = h^4(ga')(gb')(a'b') = (h^2ga'b')^2$.

=====

If I were to do it entirely on my own:

Let $h = \gcd(x,y,z); x = hx'; y= hy'; z = hz'$

$hxyz = h^4(x'y'z)$ and $h(y-x) = h^2(y'-x')$ so $hxyz$ is a perfect square if and only if $x'y'z$ is and $h(y-x)$ is a perfect square if and only if $y'-x'$ is. So wolog we may assume $h= 1$.

$\frac 1z = \frac 1x - \frac 1y$

$\frac {xy}z = y -x$. Presumable $y \ne x$ if is did we'd have $z = 0$ and $hxyz = 0^2$ and $h(y-x) = 0$ is trivial. So presume $y \ne x$

$z = \frac {xy}{y-x}$

So $y-x|xy$.

Let $g=\gcd(x,y)$ and $x=gx';y=gy'$ and $\gcd(x',y') =1$.

$y'-x'|gx'y'$. If $p$ prime is a factor of $x'$ then $p\not \mid y'$ and $p|y'-x'$. Likewise for any prime factor of $y'$. So $\gcd(y' -x',x'y') = 1$ and $y'-x'|g$. Let $y'-x' = kg$. And as $\gcd(y'-x', x'y') =1$ we know $\gcd(k, x'y') = 1$.

So $z = \frac {xy}{y-x} = \frac{gx'y'}{y'-x'} = \frac{x'y'}k$. But $\gcd(x'y',k) = 1$ so $k = 1$ and $y' - x' = g$

So that proves $y-x = g(y'-x') = g^2$ is a perfect square.

So $xyz = xy\frac{xy}{y-x} = xy\frac{xy}{g^2}=(\frac{xy}{g})^2 = (x'y)^2 = (xy')^2 = (gx'y')^2$ is a perfect square.