I was looking at the solution to this question. Basically we want to show that $\overline{C_c(\mathbb{R})}=C_0(\mathbb{R})$, under the norm $||.||_{\infty}$. This is how I understood the solution: We have $f\in C_o(\mathbb{R})$ and $\epsilon >0$ so that $\exists N>0$ such that $|x|>N \implies |f(x)|<\frac{\epsilon}{2}$. Define $g(x)=f(x)$ whenever $|x|\leq N$ and $g(x)=0$ otherwise. I can see that $g$ is continuous and bounded on $\mathbb{R}$, but does $g$ have a compact support? Is $\text{supp}(g)=\overline{\{x\in\mathbb{R}:g(x)\neq0\}}$ a closed and bounded set? I'm tempted to say that the support is $[-N,N]$, but I'm not sure if it really is. For example, there might be uncountably many zeros of $f$ in there.

-

2This approximation is too brutal. The function $g$ needs not be continuous. Imagine, for example, what would happen if you performed your approximation on the function $f(x)=e^{-x^2}$ or $f(x)=(1+x^2)^{-1}$ (note that in both cases one has $f\in C_0(\mathbb R)$, meaning that $\lim_{|x|\to \infty}f(x)=0$). – Giuseppe Negro Mar 06 '17 at 14:00

-

I edited my title. That might have confused you. – Kurome Mar 06 '17 at 14:09

2 Answers

You were close. Unfortunately your $g$ function is not continous in general (it is discontinous at $x=\pm N$). So you just have to tweak it a bit.

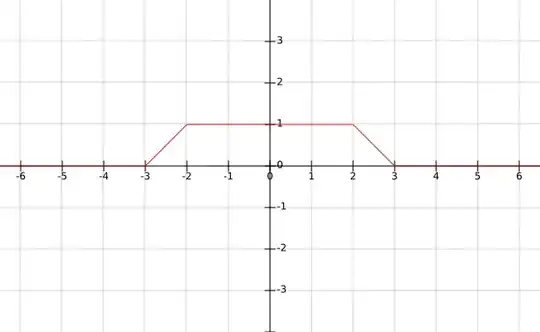

So normally you do it like that: you start with a "good" function with compact support. For any $n\in\mathbb{N}$ define

$$g_n:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}$$ $$g_n(x)=\begin{cases} 1 & \mbox{for }x\in[-n, n] \\ x+n+1 & \mbox{for }x\in[-n-1, -n] \\ -x+n+1 & \mbox{for }x\in[n, n+1] \\ 0 & \mbox{otherwise} \end{cases} $$

Draw this function and you will see why I picked it. For example $g_2$:

$g_n$ is continous (due to the pasting lemma), with compact support equal to $[-n-1, n+1]$. Also $|g_n(x)|\leq 1$ for any $x\in\mathbb{R}$ (will be later important to approximate sup norm).

Now pick $f\in C_0(\mathbb{R})$ and define $f_n(x)=g_n(x)\cdot f(x)$. Obviously $f_n$ is continous with compact support contained in $[-n-1, n+1]$ and moreover $f_n(x)=f(x)$ for $x\in[-n, n]$. So the sequence $f_n$ is what you were trying to construct. It is quite similar, except it continously passes from $f$ to constant $0$.

Note that

$$\lVert f_n-f\rVert_{\infty}\leq\sup\big\{|f(x)| : x\in(-\infty, -n]\cup[n, \infty)\big\}$$

(this you can calculate on your own I hope) and since $f$ vanishes at infinity then this means that $f_n\to f$ in sup norm.

So now since for any $f\in C_0(\mathbb{R})$ there is a sequence $(f_n)\subset C_c(\mathbb{R})$ such that $f_n\to f$ then $C_0(\mathbb{R})\subseteq \overline{C_c(\mathbb{R})}$. The other inclusion follows pretty much from the definition of both $C_0$ and $C_c$.

- 42,851

-

I understand that you pretty much 'smoothened' my $g$ above, but my initial question still stand, why does your $f_n$ have compact support in $[-n-1,n+1]$? We do not know anything about $f_n$ in $[-n-1,n+1]$ aside from the fact that it is continuous there. But I heard there are continuous functions in closed intervals that have uncountably many zeros. – Kurome Mar 07 '17 at 09:33

-

Woops, I took a look at the definition of support again. It is the closure of the set in which $f$ is non zero. So trivially, every support is closed. Therefore, we only have to show that it must be bounded, and clearly, $[-n-1,n+1]$ is bounded, so the support inside it must be bounded as well. Therefore we have a compact support for $f_n$ above. Thanks. – Kurome Mar 07 '17 at 09:58

-

@Kurome Yes, support is closed by definition being the closure of the set of non-zeros (which is open). – freakish Mar 07 '17 at 10:02

A deep solution:

A function in $C_0(R)$ or in $C_c(R)$ can be identified as a fnction on $R$'s one-point compactification. The former are those that are zero at infinity (say the $N=(0,1)$ on the circle) while the latter are those that are zero not just at $N$ but also in a neighborhood of it.

Now question is: Are functions that are zero in a neighborhood of $N$ in dense in the set of functions that vanish at $N$ in the supremum topology?

Yes.

Note 1: This proof works for every locally compact space, eg. $R^n$! Local compactness guarantees the existence of 1-point compactification.

Note 2: There is so much to this proof. We can assert the same density for smooth versions. And if need be, we can work with cutoff functions centered at the infinity to construct certain functions, etc. It is just so much easier to work with infinity when it becomes just another point on your space!

- 5,024