I think the following example explains the fundamental theorem of calculus quite intuitively. Or more precisely, that's what I thought; now I'm starting to have some doubts.

Suppose $v(t)$ is the velocity of a car driving along the highway. The units for $t$ are in hours and the units for $v(t)$ are in miles per hour. Assume $v(t)$ is continuous and nonnegative. What is the displacement of the car over one hour (ie., $t \in [0,1]$)?

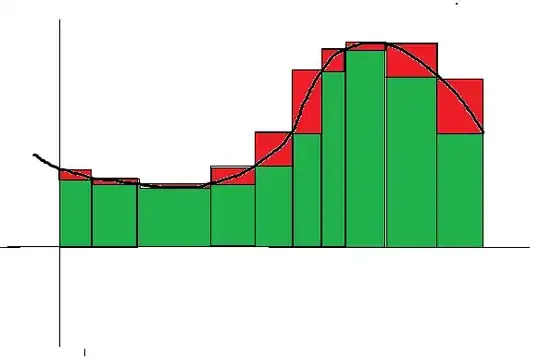

Well, if we subdivide $[0,1]$ into $n$ subintervals of equal length, in each subinterval $\left[\frac{k}{n}, \frac{k+1}{n}\right]$ the velocity doesn't change too much for large $n$ and hence can be approximated by $v(\frac{k}{n})$. Therefore, the displacement in $\left[\frac{k}{n}, \frac{k+1}{n}\right]$ is equal to $\frac{1}{n} v(\frac{k}{n}) + \epsilon(k, n)$ where $\epsilon(k, n)$ is a small error dependent on $k$ and $n$.

Hence $$ \text{Displacement} = x(1) - x(0) = \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} \frac{1}{n} v\left(\frac{k}{n}\right) + \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} \epsilon(k, n) $$

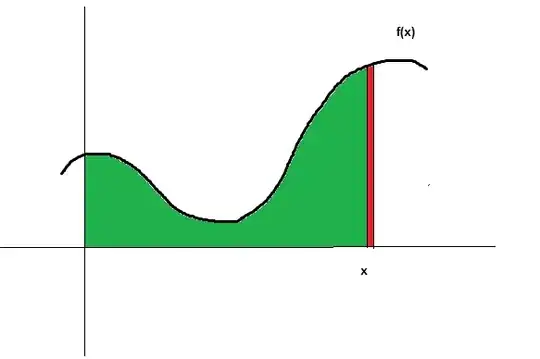

Note that the above equality holds for all $n$, since we have accounted for the error. If we assume that $ \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} \epsilon(k, n) \to 0$ as $n \to \infty$, then it's easy to see that $$x(1) - x(0) = \lim \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} \frac{1}{n} v\left(\frac{k}{n}\right) = \int_0^1 v(t) \ dt$$

However, it's not obviously clear to me why $\sum_{k=0}^{n-1} \epsilon(k, n) \to 0$ as $n \to \infty$. Why should this hold intuitively?