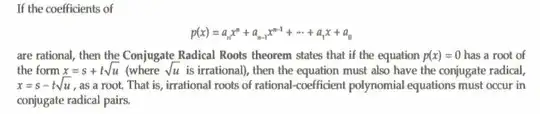

Here, what are exactly $s$. $t$ and $u$? Are they rational numbers with $u$ being nonnegative? There is no exact explanation of the theorem. So I am confused..

-

Yes, rational numbers. – Billy Feb 27 '18 at 15:47

-

Does $u$ necessarily have to be nonnegative? – Keith Feb 27 '18 at 15:48

-

I think the statement of the theorem ("$\sqrt{u}$ is irrational") means that it wants you to interpret it that way. But, actually, this theorem does still hold even when u is negative. (The proof they give might not, though!) – Billy Feb 27 '18 at 15:50

-

Thanks for asking this question! I see that you have a number of responses, so please upvote (by pressing the up arrow) any answers that you found helpful. If you feel like your question has been answered, please press the checkmark to accept the answer that best answers your question. – Stella Biderman Feb 27 '18 at 16:55

-

The last sentence in the text is FALSE. It is true that IF $s+t\sqrt u; $ is a root , with$ s,t,u\in \Bbb Q$ where $ u$ is not the square of a rational THEN $s-t\sqrt u;$ is also a root. But it is NOT true that there must be a root that can be expressed in radicals over $\Bbb Q.$ That is , it can happen that all applications of the operations $+,-,\times,$ and $n$th powers (for $n\in \Bbb Z$) and $n$th roots (for $n\in \Bbb N) $ ( including any complex-valued $n$th roots), applied to members of $\Bbb Q,$ will fail to produce a root of $p.$ – DanielWainfleet Feb 27 '18 at 19:11

3 Answers

Let $u\in \Bbb Q \setminus \{q^2:q\in \Bbb Q\}.$ Let $\sqrt u$ denote some (fixed) $z\in \Bbb C$ such that $z^2=u.$

Let $\Bbb Q[z]=\{a=s+tz:s,t\in \Bbb Q\}.$

Exercise : $\Bbb Q \subset \Bbb Q[z],$ and $\forall x,x'\in \Bbb Q[z]\;(x+x'\in \Bbb Q[z]\land xx'\in \Bbb Q[z]).$

Exercise: If $s,s',t,t'\in \Bbb Q$ then $s+tz=s'+t'z\iff (s=s'\land t=t').$ Corollary: For each $x\in \Bbb Q[z]$ there is a unique pair $(s,t)\in \Bbb Q^2$ such that $x=s+tz.$

For $s,t\in \Bbb Q$ and $x=s+tz$ let $f(x)=s-tz.$ Note that $f(x)$ is well-defined by the above corollary.

Exercise:

(i). $\forall q\in \Bbb Q\;(q=f(q)).$

(ii). $\forall x\in \Bbb Q[z]\;( f(x)=0\iff x=0)$.

(iii). $\forall x,x'\in \Bbb Q[z]\;(f(x+x')=f(x)+f(x')\land f(xx')=f(x)f(x')).$

(iv). By (iii) and by induction on $j\in \Bbb N$ we have $\forall j\in \Bbb N\;(f(z^j)=f(z)^j\;).$

From these exercises, if $x\in Q[z]$ then $p(x)\in \Bbb Q[z]$ and $$f(p(x))=f(\sum_{j=0}^na_jx^j) =\sum_{j=0}^nf(a_jx^j) =$$ $$=\sum_{j=0}^nf(a_j)f(x^j)=\sum_{j=0}^n a_jf(x)^j=p(f(x)).$$ So for any $x \in \Bbb Q[z],$ we have $p(x)=0\iff p(f(x))=0.$

Some parts of the exercises are obvious but all of it is needed for the conclusion.

- 57,985

-

$Q[z]$ is a field: If $s.t\in \Bbb Q$ and $0\ne s+tz$ then $s^2-t^2z^2=s^2-t^2u\ne 0 ,$ and $(s+tz)^{-1} =(s-tz)/(s^2-t^2u)=f(s+tz)/(s^2-t^2u)\in \Bbb Q]z].$ The function $ f$ is called an involution because it is a field-isomorphism and $f(f(x))=x.$ – DanielWainfleet Feb 27 '18 at 20:07

All three of $s,t,$ and $u$ are rational numbers. For a proof of the theorem, see here.

By this theorem (which is what comes to my mind first when I hear "the conjugate root theorem"), $u$ does not need to be non-negative.

- 31,155

In simple terms, the rational root theorem states:

For a function $f(x)$, if that function has a root in the form of $a+bi$, where $a$ and $b$ are coefficients, then that function also has a root at $a-bi$.

That is, if $f(a+bi)=0$, then $f(a-bi)$ must equal $0$.