Ok, this is going to be a bit abstract question:

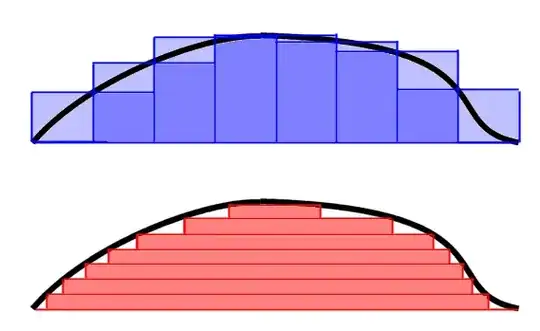

When you define the Riemann integral of a function, you first define what a step function is and you define its integral - basically the sum of the areas of the rectangles with the respective sign. Then you define the lower integral - being the supremum of the integrals of all step functions which are less than the given function, and similarly, you define the upper integral. Finally, you claim that a function is Riemann integrable if its upper integral coincides with its lower one.

When you define the Lebesgue integral (or in general, against a measure), you similarly define the set of simple non-negative functions and define their integral. But then, for a general non-negative function, you take its integral to be just the supremum of the set of all integrals of the set of non-negative functions which are less than the given one.

My question is: Why do we define the integral against a measure to involve only the supremum? Why don't we define the "upper integral" as well? Is it because of the non-negativity condition?