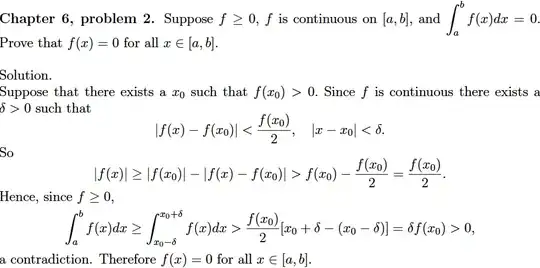

Possible Duplicate:

$f\geq 0$ and $\int_a^b f=0$ implies $f=0$ everywhere on $[a,b]$

Is this a correct solution?

Thanks for your help

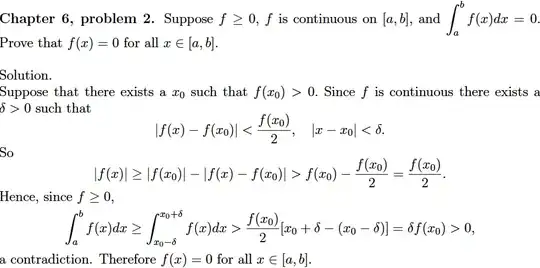

Possible Duplicate:

$f\geq 0$ and $\int_a^b f=0$ implies $f=0$ everywhere on $[a,b]$

Is this a correct solution?

Thanks for your help

Here is another approach (I prefer 'constructive' proofs, albeit they tend to be longer, as is the case here):

Since $\int f = 0$, and $f$ is continuous, we have $\int f = \sup_{\pi \in {\cal P}} L(f,\pi) = 0$, where ${\cal P}$ is the set of partitions of $[a,b]$, and $L(f,\pi)$ is the Riemann sum. Since $[a,b]$ is compact, $f$ is uniformly continuous.

Let $\epsilon>0$. Choose $\delta>0$ so that if $|x-y| < \delta$, then $|f(x)-f(y) | < \epsilon$. Choose a partition $\pi$ with $\text{mesh } \pi < \delta$. Since $f \geq 0$, we have $L(f,\pi) = 0$, and hence on every subinterval $[x,y]$ of $\pi$, we have some $\xi$ such that $f(\xi) = 0$. Uniform continuity shows that $f(t) < \epsilon$ for all $t \in [x,y]$. Hence $f(t) < \epsilon$ for all $t \in [a,b]$. Since $\epsilon>0$ was arbitrary, we are finished.