Let $f$ be a function, $f:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}$

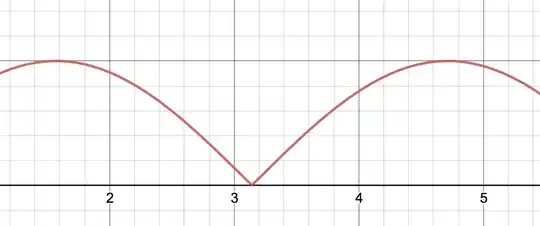

$$f(x)=\begin{cases} e^{x^2}-2 & x< 0 \\ x^3+x-1 & 0\leq x \leq 1 \\ \left|\sin(x)\right| & x>1. \end{cases}$$

Check if $f$ is continuous and differentiable at $a$, when $a=0,1,\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi$. If $f$ is differentiable at $a$, find $f'(a)$.

What I've been doing:

I found that:

- $f$ is continuous at $0$ but not differentiable.

- $f$ is not continuous at $1$ so it's not differentiable.

And then I thought that $f$ was differentiable at $\pi$ and $\frac{\pi}{2}$ because $f$ is continuous at $(1, +\infty)$ ($\left|\sin(x)\right|$), so I looked for:

- $f'(\frac{\pi}{2})=\left|\cos(\frac{\pi}{2})\right|=0$ (by the solution my prof gave me this is correct).

- $f'(\pi)=\left|\cos(\pi)\right|=-1$ Now this is wrong. The solution they gave me says that $f$ is not differentiable at $\pi$, and I'm really lost. Why is it differentiable at $\frac{\pi}{2}$ and not $\pi$?