You can derive the properties of quaternions through clifford algebra and the geometric product of vectors.

The geometric product works like so:

$$e_a e_b = \begin{cases} 1, & a = b \\ -e_b e_a, & a \neq b \end{cases}$$

where $a, b$ can be $x$, $y$, or $z$ as usual. This captures both the work of the cross product and the dot product in one product of basis vectors.

You can then identify

$$\begin{align*}

i &= -e_y e_z \\

j &= -e_z e_x \\

k &= -e_x e_y

\end{align*}$$

And then the properties of quaternions naturally follow.

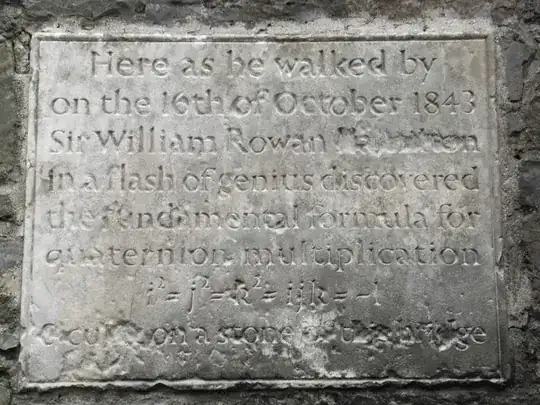

$$i^2 = (-e_y e_z)(-e_y e_z) = (e_y e_z)(e_y e_z) = -e_y (e_z e_z) e_y = -e_y e_y = -1$$

And similarly for $j^2$ and $k^2$, as well as the $ijk$ product:

$$ijk = (-e_y e_z)(-e_z e_x)(-e_x e_y) = - e_y e_z e_z e_x e_x e_y = -e_y (e_z e_z)(e_x e_x) e_y = -e_y e_y = -1$$

This allows you to interpret quaternions in a very geometric way: the $i,j,k$ do not represent vectors, but rather oriented planes. It's just that in 3d each plane has a unique normal vector, so we often abuse this duality.