Curiosity

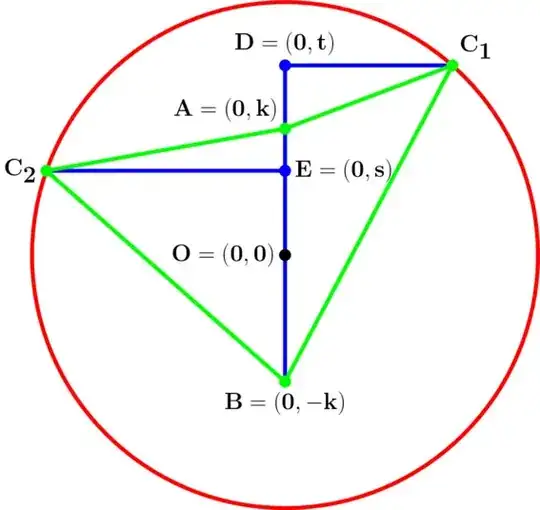

Let $\mathscr{C}$ be a circle of radius $r$, centered at the origin.

Assign point $O$ the cartesian coordinate $(0,0).$

Let $k$ be a fixed element in $(0,r).$

Set points A and B to have cartesian coordinates $(0,k)$ and $(0,-k)$ respectively.

Choose point C at random on $\mathscr{C}.\;$ Then $\;\left|\;\overline{OC}\;\right|^2 = r^2.$

The end of this query gives an Algebraic Demonstration that

regardless of the point $C$ chosen,

$\;\left|\;\overline{AC}\;\right|^2 + \left|\;\overline{BC}\;\right|^2 = 2(r^2 + k^2).$

Questions

Question 1 below added, per Blue's suggestion.

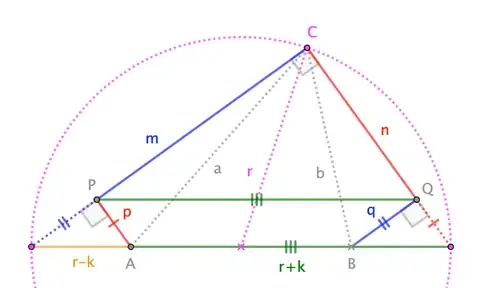

- see this query's Background section (the next section). My underlying desire is to find a non-algebraic way of predicting that

given $\;z_1,z_2 \in \mathbb{C}\;$ the Locus of $\;\{z\; :\; |z-z_1|^2 + |z-z_2|^2 \;=\;$ a constant$\}\;$ will be a circle. I have accepted Blue's answer, re Appollonious' (triangle-oriented) theorem, which does facilitate the prediction, though the logic is convoluted. I would welcome a separate circle-oriented geometry theorem that more directly facilitates the prediction.

The remaining questions in this section are now somewhat redundant, but are left in as a reference to how I originally posed my questions.

Can this result be demonstrated geometrically, without resorting to algebra?

Does this result have a (theorem) name?

Is there a free online geometry resource (e.g. pdf) that includes this result?

Background

In "An Introduction to Complex Function Theory", Bruce Palka, 1991, problem

4.6.vii, p.26 specifies:

geometrically describe $\;\{z\;:\;\left|z-i\right|^2 + \left|z+i\right|^2 = 4\}.\;$

After determining that the Locus was a circle of radius 1, centered at the origin,

I realized that

if the right hand side $\; = R \;: \;R>2\;$ then the Locus is a circle of radius

$\;\sqrt{(R-2)/2}.$

My (brief) subsequent online research found no mention of this curious result.

Algebraic Demonstration

In the diagram at the end of this query, $\;\mathscr{C}, r, k,\;$ point $A$ and point $B$ are as described in the Curiousity section, at the start of this query.

Randomly choose $t$ in $\;(k, r)\;$ and assign point $D$ the cartesian coordinates $(0,t).$

Let point $C_1$ represent the right-hand-side intersection of $\;\mathscr{C}\;$ with the line $\;y=t.$

Similarly, randomly choose $s$ in $\;(0,k),\;$ and assign point $E$ the cartesian coordinate $\;(0,s).$

Similarly, let point $C_2$ represent the left-hand-side intersection of $\;\mathscr{C}\;$ with the line $\;y=s.$

$\left|\;\overline{DC_1}\;\right|^2 \;= \;r^2 - t^2.$

$\left|\;\overline{AC_1}\;\right|^2 \;= \;(t-k)^2

+ \left|\;\overline{DC_1}\;\right|^2.$

$\left|\;\overline{BC_1}\;\right|^2 \;= \;(t+k)^2

+ \left|\;\overline{DC_1}\;\right|^2.$

$\left|\;\overline{AC_1}\;\right|^2

+ \left|\;\overline{BC_1}\;\right|^2

\;= \;2(t^2 + k^2) \;+ \;2(r^2 - t^2) \;= \;2(r^2 + k^2).$

$\left|\;\overline{EC_2}\;\right|^2 \;= \;r^2 - s^2.$

$\left|\;\overline{AC_2}\;\right|^2 \;= \;(k-s)^2

+ \left|\;\overline{EC_2}\;\right|^2.$

$\left|\;\overline{BC_2}\;\right|^2 \;= \;(k+s)^2

+ \left|\;\overline{EC_2}\;\right|^2.$

$\left|\;\overline{AC_2}\;\right|^2

+ \left|\;\overline{BC_2}\;\right|^2

\;= \;2(k^2 + s^2) \;+ \;2(r^2 - s^2) \;= \;2(r^2 + k^2).$