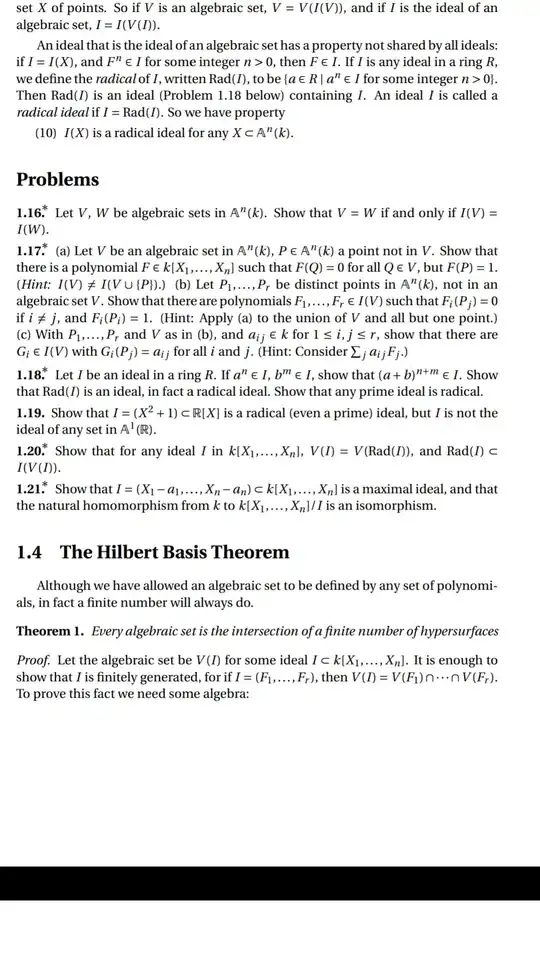

I'm trying to solve problem 1.18 in Fulton's 'Algebraic Curves', which is illustrated in the attached image, but I'm having some difficulties understanding the first part.

The ring R is assumed to be commutative and unital, so the first thing that came to mind was to consider the binomial expansion of $(a+b)^{n+m}$, but I don't see why powers of $a$ which are less than n, or powers of $b$ which are less than m should be contained in the ideal.

An explanation as to how I can show that $Rad(I) $ contains $a+b$ would be appreciated, particularly I'd like to know if one can indeed be guaranteed the containment (in I) of the aforementioned terms from the binomial expansion.

I suspect that I may be missing or forgetting some ring theoretic fact.