Given function $f(\vec x) \in \mathbb R, \vec x \in \mathbb R^n $, We know that for all unit direction $\hat u$:

$$ \partial_{\hat u} f = \hat u \cdot \nabla f $$

Consider function $f$:

$$ f(\left<x,y,z\right>) = z - \min(\lvert x \rvert, \lvert y \rvert)\times\frac{\lvert y \rvert}{y} $$ At the origin, along direction $\hat u=\left<\frac{1}{\sqrt 3}, \frac{1}{\sqrt 3}, \frac{1}{\sqrt 3} \right>$: $$ \partial_{\hat u} f(\vec 0) = \lim_{t \to 0} \frac{f(t \hat u) - f(\vec 0)}{t} = \lim_{t \to 0} \frac{\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt 3} - \min\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt 3},\frac{1}{\sqrt 3}\right)\times 1\right) - 0}{t} = \lim_{t \to 0} \frac{0 - 0}{t} = 0\\ \hat u \cdot \nabla f(\vec 0) = \hat u \cdot \left<f_x,f_y,f_z \right> = \left<\frac{1}{\sqrt 3}, \frac{1}{\sqrt 3}, \frac{1}{\sqrt 3} \right> \cdot \left<0,0,1\right> = \frac{1}{\sqrt 3}\\ \partial_{\hat u} f(\vec 0) \ne \hat u \cdot \nabla f(\vec 0) $$

So there must be other requirements for:

$$ \partial_{\hat u} f = \hat u \cdot \nabla f $$

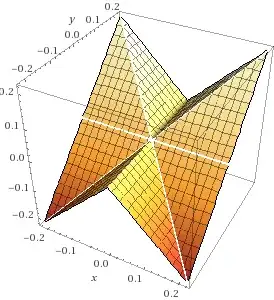

From the graph of the function $f$, we can see that even the directional derivative is defined for all direction at the origin, the tangent surface at the origin is not a plane.

Here are my questions:

- does $\nabla f(\vec 0)$ exist ?

- what's the requirement for $\partial_{\hat u} f = \hat u \cdot \nabla f$

Edit: Proof that $f$ is not differentiable at the origin

For $f$ to be differentiable, there is a linear transformation $T$ such that: $$ \lim_{\lVert \mathbf h\rVert \to 0} \frac{f(\mathbf a+\mathbf h)-f(\mathbf a)-T_a(\mathbf h)}{\lVert \mathbf h\rVert} = \mathbf 0. $$ Since $\mathbf h$ can approach to $\mathbf 0$ follow any trajectory, assume $\mathbf h$ is following direction $\hat u$, $\mathbf h = t \hat u$ and $\lVert \hat u \rVert = 1$, then we have: $$ \lim_{t \to 0} \frac{f(\mathbf a+t \hat u)-f(\mathbf a)-T_a(t \hat u)}{t} = 0\\ \lim_{t \to 0}\frac{f(\mathbf a+t \hat u)-f(\mathbf a)}{t} = \lim_{t \to 0}\frac{T_a(t \hat u)}{t}\\ $$ To the left we have: $$ \lim_{t \to 0}\frac{f(\mathbf a+t \hat u)-f(\mathbf a)}{t} = \partial_{\hat u} f(a) $$ To the right, since $T$ is linear, we have: $$ \lim_{t \to 0}\frac{T_a(t \hat u)}{t} = \lim_{t \to 0}\frac{t T_a(\hat u)}{t} = T_a(\hat u) $$ So $$ \partial_{\hat u} f(a) = T_a(\hat u) $$ $T$ is linear and I have already proofed that $\partial_{\hat u} f(0)$ is not linear (above in the question). So $f$ is not differentiable at the origin.

What have surprised me is that I thought linearity of $\partial_{\hat u} f$ is a property of differentiable function, but in reality, it is a requirement. Although, technically there is no difference between property and requirement, they are both $\Rightarrow$ in math world.