A partition of a positive integer $n$ is a multiset of positive integers that sum to $n$. We denote the number of partitions of $n$ by $p(n)$. Also, let $p(n, k)$ be the number of partitions of $n$ into "exactly" $k$ parts. Then

$$p(n) = \sum_{k=1}^{n} p(n, k).$$

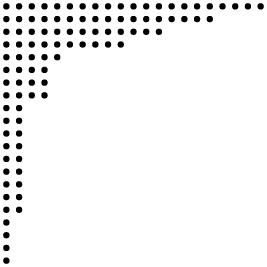

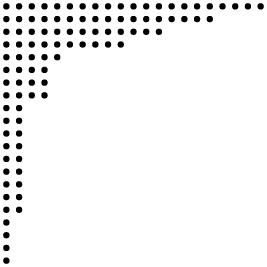

Now, consider Ferrers diagram, where the $n$th row has the same number of dots as the $n$th term in the partition.

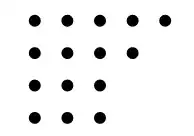

A conjugate of a partition is the Ferrers diagram, where its rows and columns are flipped. For example,

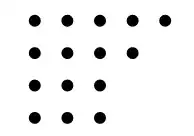

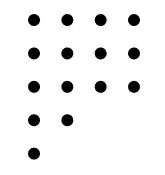

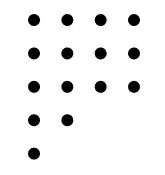

This Ferrers diagram represents the partition $15 = 5 + 4 + 3 + 3$, and the conjugate partition of this is represented as :

where $15 = 4 + 4 + 4 + 2 + 1.$ Using this, we can easily recognize that the number of partitions of $n$ with largest part $k$ is the same as the number of partitions into $k$ parts, which is $p(n, k)$. Now we can conclude that the number of partitions of $n$ with all its parts equal or less than $k$, is the same as the number of partitions with equal or less than $k$ parts.

Now, back to the problem :

$$x+2y+3z = n.$$

Notice something? Now look at this :

$$x \cdot 1 + y \cdot 2 + z \cdot 3 = n.$$

We have to make $n$ with $x$ $1$s, $y$ 2s, and $z$ 3s. This equals the number of partitions of $n$, where each part is equal or less than $3$ - since we can only use $1, 2, 3$. Therefore, here's the final answer :

$$p(n, 3) + p(n, 2) + p(n, 1).$$

and one can easily show that $p(n, 1) = 1,\:\:p(n, 2) = \lfloor \frac{n}{2} \rfloor,\:\:p(n, 3) = \rm{round} \left( \frac{n^{2}}{12} \right)$ where the round function gives the nearest integer.

Finally the answer is :

$$\boxed{1 + \lfloor \frac{n}{2} \rfloor + \rm{round} \left( \frac{n^{2}}{12} \right)}$$

and we get $8$ for $n=7$. Read this for more explanation on the identity I used(and Ferrers diagram).