The expression $\displaystyle \frac{(x-1)(x+1)}{(x-1)}$ cannot be evaluated at $x = 1$ because that would require division by zero, which is undefined. No one is dividing by zero or making a new rule to allow some kind of special kind of dividing by zero (although it can look like that at first).

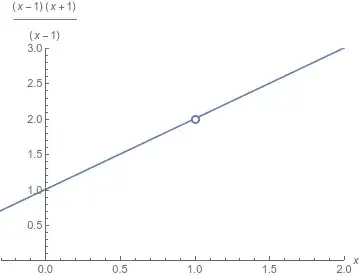

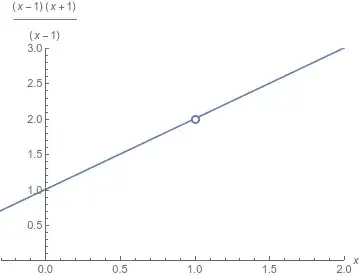

The limit $\displaystyle \lim_{x \rightarrow 1} \frac{(x-1)(x+1)}{(x-1)}$ is a slightly different object than the fraction we started with. We never let $x = 1$ while evaluating it. Instead, we ask "from the graph of this function, what would the closest neighbors on the left and right predict should be the value of the function at $x = 1$?" So what is that graph?

Notice the hole in the graph at $(1,2)$. This is a one point gap in the graph caused by the division by zero at $x = 1$. Consequently, this graph is discontinuous at $x = 1$. Nevertheless, we can ask the neighbors what value should be taken at that missing point, if we were to assume that the function was continuous at that point. And, by looking, we see that the neighbors tell us the value would be $2$ if the function were continuous at that point. So we have

$$ \lim_{x \rightarrow 1} \frac{(x-1)(x+1)}{(x-1)} = 2 \text{.} $$

However, no one wants to have to produce a graph every time we evaluate a limit. So we want a symbolic way to attack this. Notice that the interesting behaviour is introduced by the $x-1$ factors; the $x+1$ factor is just "along for the ride". So we factor the easy stuff out of the limit, immediately evaluating it at $x=1$ and leave the interesting stuff in it.

$$ \lim_{x \rightarrow 1} \frac{(x-1)(x+1)}{(x-1)} = (1+1) \lim_{x \rightarrow 1} \frac{x-1}{x-1} \text{.} $$

We should recognize that what is inside the limit is easy to evaluate at the neighbors of $x=1$ and when we do we always get $1$. So the neighbors predict that the value of this simpler limit is $1$. That is,

$$ \lim_{x \rightarrow 1} \frac{(x-1)(x+1)}{(x-1)} = (1+1) \cdot 1 = 2 \text{.} $$

We are hoping for some sort of balance between the zero-ness from the factor in the numerator and undefined-ness from the factor in the denominator. And that hope is met -- the resulting numerator and denominator both approached zero in exactly the same way, giving the ratio $1$ everywhere we can evaluate it.

Another way to say this is that $x+1$ is the continuous function that agrees with $\displaystyle \frac{(x-1)(x+1)}{(x-1)}$ at every point of the domain of that fraction (which excludes $x = 1$). (More to say about this at the end.)

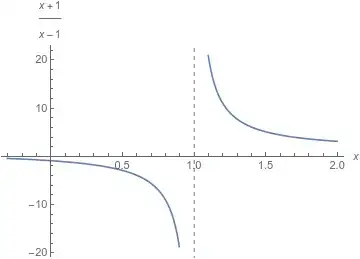

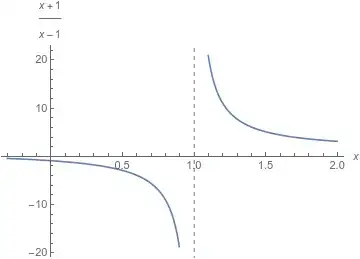

It is important to note that the "interesting factors" cancelled out. If they do not, the neighbors do not give a sensible prediction for the continuous function obtained by filling in the gap. Consider $\displaystyle \lim_{x \rightarrow 1} \frac{x+1}{x-1}$, having the graph

The neighbors to the left of $x=1$ predict the height of the function is less than any number you care to name, which we normally abbreviate to "predict the height $-\infty$". The neighbors to the right predict a height greater than any number you care to name, abbreviated to $\infty$. Since the two sides can't agree on the value to fill in the gap, there is no continuous function that agrees with $\frac{x+1}{x-1}$ away from $x=1$ and is also defined at $x = 1$.

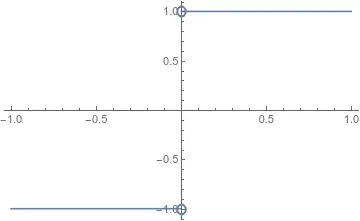

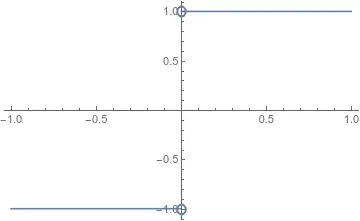

The kind of gap ("discontinuity") in $\frac{(x-1)(x+1)}{(x-1)}$ is called "removable" because the function approaches the same value from the left and from the right. There are other kinds of discontinuity where the left and right don't agree. Particular (named) examples are

- jump discontinuity, where the approaches from the left and from the right each give a finite prediction for the value in the gap, but do not agree on the value of that prediction. For instance the function $f(x) = \begin{cases} 1 ,& x>0 \\ -1 ,& x < 0 \end{cases}$ at $x = 0$.

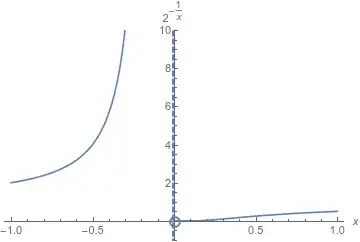

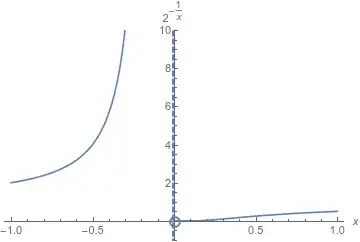

- infinite discontinuity, where the approach from one side or the other (or both) goes to either $\infty$ or $-\infty$. A different example from the one above (with the vertical asymptote) is $f(x) = 2^{-1/x}$.

- and there are others. An example of a more exotic discontinuity comes from the function $\sin(1/x)$. It has infinitely many oscillations in a neighborhood of $x = 0$, so the neighbors try to predict every value from $-1$ to $1$ as the value to fill in at $x = 0$. But a function can't take every value in $[-1,1]$ at $x=0$, so this limit fails to exist.

A bit more about the $x+1$: When we factored out the "$x+1$", we were factoring out the part that is continuous at $x = 1$ and leaving in the part that was zero or undefined at $x = 1$ inside and unevaluated. An important property of continuous functions, typically taken as their definition once one has a workable definition of a limit, is that continuous functions agree with their limits at every point of their domain. We know that we can graph $x+1$ without lifting our pencil -- it's a line. So $x+1$ is continuous, so we can evaluate a limit of $x+1$ by just substituting for $x$ the value $x$ is approaching. So we find $\displaystyle \lim_{x \rightarrow 1} x+1 = 1+1 = 2$ because $x+1$ is continuous.

Notice that $\displaystyle \frac{(x-1)(x+1)}{(x-1)}$ is continuous everywhere its denominator is not zero. Consequently, we can evaluate its limits for $x$ approaching any value except $1$ by just substituting in the value $x$ is approaching. The takeaway is that most functions you work with will be continuous at most places -- we need to be able to recognize where a function is discontinuous and recognize that limits will be a little harder to evaluate at discontinuities. But a good starting strategy is to split the function into the part that is continuous there and the part that is discontinuous there, so you can be done with the continuous part immediately by evaluating and focus your efforts on the remaining discontinuous part.