Using the standard tangent half-angle substitution, we get $$\int \frac{1}{2-\cos(x)}\,dx = \frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}\tan^{-1}(\sqrt{3}\tan\frac{x}{2}) + C$$ The resulting antiderivatives are piecewise continuous functions with discontinuities at $x = (2k+1)\pi$. However, the integrand is continuous everywhere, so any antiderivative must be continuous everywhere (??) according to FTC. So, how do we deal with this problem? What is the correct form of the antiderivatives? Is there a form that avoids the discontinuities?

-

To address one part of your question - that is definitely the correct antiderivative. When I differentiate it, I get the integrand. – Varun Vejalla Oct 17 '19 at 01:10

-

Searching up "discontinuous function with continuous derivative" gave me this question. – Varun Vejalla Oct 17 '19 at 01:11

-

@automaticallyGenerated The problem is at the points of discontinuities. You can't differentiate there but you should be able to. – bjorn93 Oct 17 '19 at 01:25

-

It's because of the restricted range on the $\tan^{-1}$ – Varun Vejalla Oct 17 '19 at 01:26

3 Answers

Your problem is the $+C$ term. Take for example $\frac{1}{x}$. Its most general antiderivative is usually given as

$$\int \frac{1}{x}dx = \ln|x| + C$$

But this is not correct. Notice that the piecewise function

$$f(x)=\begin{cases} \ln(-x) +2 & x < 0\\ \ln(x) -1 & x> 0\\ \end{cases}$$

is also an antiderivative of $\frac{1}{x}$, even thought the $+C$'s on both sides were different. So any time your integrand has a singularity, the integration constant is allowed to change when you cross it.

On the domain when you integrated, the $+C$ are only uniform between the discontinuities. Otherwise, each discontinuous piece must have its own $+C$. And one can choose a series of $+C$'s such that the resultant antiderivative is continuous.

$\mathbf{EDIT}$: In this case, the continuous antiderivative should be of the form:

$$\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}\tan^{-1}\left(\sqrt{3}\tan\left(\frac{x}{2}\right)\right) + \frac{2\pi}{\sqrt{3}}\Bigr\lfloor \frac{1}{2\pi}x+\frac{1}{2}\Bigr\rfloor + C$$

This function is both continuous and differentiable at its former discontinuities, even though it may not look like it at first glance.

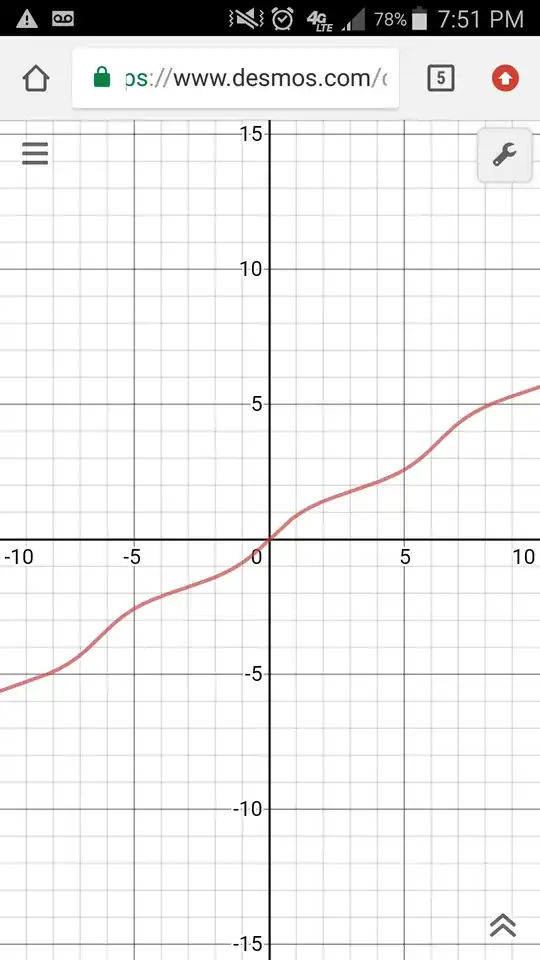

And a graph of the fixed function, courtesy of Desmos:

- 34,407

-

-

2@bjorn93 Sure. Take the limit as $x\to\pi$ for example. The limit from the left approaches $\frac{\pi}{\sqrt{3}}$, but the limit from the right approaches $-\frac{\pi}{\sqrt{3}}$, so at that step we need to add $\frac{2\pi}{\sqrt{3}}$. Now, if we raised that piece by that amount, then we need to raise the next piece by twice that amount at the next discontinuity to meet up with this piece at $x=3\pi$ since the limit from the right increased, but the limit from the right is still $\frac{\pi}{\sqrt{3}}$. This translates into a greatest integer "staircase" with that step size and that dilation. – Ninad Munshi Oct 17 '19 at 02:50

-

Can't edit anymore but the last limit from right should say $-\frac{\pi}{\sqrt{3}}$ – Ninad Munshi Oct 17 '19 at 02:56

-

A question: is $\Bigr\lfloor \frac{1}{2\pi}x+\frac{1}{2}\Bigr\rfloor$ a part of the constant? How could it be a constant if it contains an $x$-value? Or is that only to say that it is a constant in each "piece" or interval, rather than write in a piece-wise fashion? – Bored Comedy Jan 06 '23 at 02:37

-

@BoredComedy the point of the $+C$ in antiderivatives is not to be constant, it is to be in the kernel of the derivative operator. That is to say that $+C$ is really a function such that $$\frac{d}{dx}(C) = 0$$ in the domain we care about. – Ninad Munshi Jan 08 '23 at 06:16

-

Thanks for the response! Coming from a person who just finished Calc II a couple of weeks ago, this is really interesting. I don't really know what a kernel is. (I assume it's a linear algebra thing?) But in this case $C(x)= \frac{2\pi}{\sqrt{3}}\Bigl\lfloor \frac{1}{2\pi}x+\frac{1}{2}\Bigr\rfloor + M$, right? Then how would $\frac{d}{dx}(C) = 0$? Sorry if this is very obvious! – Bored Comedy Jan 08 '23 at 22:50

-

@BoredComedy graph that function you wrote. What does it look like and what is its slope? – Ninad Munshi Jan 10 '23 at 08:38

-

It's 0. However, isn't the function $C$ discontinuous? (According to the definition, the limit from the left and right should be equal to the value of the function at the point of interest). In this case, shouldn't the limit of the function $C$ not exist as the two-sided limits are not equal at, say, $\pi$, so how is it derivative defined at that point? Again, sorry if this is obvious! – Bored Comedy Jan 11 '23 at 19:45

Although I'm really late with the answer, here's something other people might find interesting.

There is a continous elementary antiderivative,

$$F(x)=\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}\left(\frac{x}{2}+ \tan^{-1}\left(\frac{\left( \sqrt{3}-1 \right)\tan\frac{x}{2}}{1+\sqrt{3}\tan^2\frac{x}{2}}\right)\right)$$

— but finding it may be somewhat inconvenient. Here's the how.

First of all, we carefully look at the function $\tan^{-1}\left(\tan x\right)$. Quite interesting plot, isn't it?

So, we see (check it!) that the floor function can be written as $$\mathbb{floor}(x)=\frac{2x-1}{2}-\frac{1}{\pi} \tan^{-1}\left(\tan\left( \frac{2x-1}{2}\pi \right)\right)$$

Next, we find the precise floor expression that eliminates the discontinuities in your antiderivative. That part of the work is already done in one of the answers, $$\left \lfloor \frac{1}{2}\left( \frac{x}{\pi}+1 \right) \right \rfloor = \frac{1}{\pi}\left( \frac{x}{2}-\tan^{-1}(\tan(\frac{x}{2}))\right) $$

Then you add this staircase function to your antiderivative, and end up with $$F(x)=\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}} \left[ \tan^{-1}\left(\sqrt{3}\tan\frac{x}{2}\right)+\frac{x}{2}-\tan^{-1}\left(\tan\frac{x}{2}\right) \right] $$ which is already cool if you don't mind stuff like $\tan^{-1}(\tan(x))$. But since we can combine inverse tangent sums by using the formula $\tan^{-1}(a)+\tan^{-1}(b)=\tan^{-1} \left( \frac{a+b}{1-ab} \right)$, we can go even further!

Combining inverse tangents and simplifying the resulting expression, we finally get a fully continuous antiderivative $F$ that we can use to calculate definite integrals without paying attention to the limits.

- 183

Suppose you want to it from $x=0$ to $2\pi$ using $\tan(x/2)=t$. A transformation $t(x)$ needs to be continuous and monotonic (without max/min). But $(x)=\tan(x/2)$ is discontinuous at $x=\pi$, so it is a bad substitution. A bad substitution can be made to work but breaking the domain of integration at the discontinuities.

One way is

$$I=\int_{0}^{2\pi} \frac{dx}{2-\cos x}= \int_{0^+}^{\pi^-}\frac{dx}{2-\cos x} +\int_{\pi^+}^{2\pi^-}\frac{dx}{2-\cos x}.$$ This way $\tan(x/2)|_{x=\pi^-}=+ \infty$ and $\tan(x/2)|_{\pi^+}=-\infty.$ So you get $$I=\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}[(\frac{\pi}{2}-0)+(0- \frac{-\pi}{2})]=\frac{2\pi}{\sqrt{3}}.$$

Else, the other way is

You may directly use the domain reduction by $$\int_{0}^{2a} f(x) dx=2\int_{0}^{a} f(x) dx, ~if~ f(2a-x)=f(x).$$ You get $$I=2\int_{0}^{\pi^-} \frac{dx}{2-\cos x}.$$

- 43,235