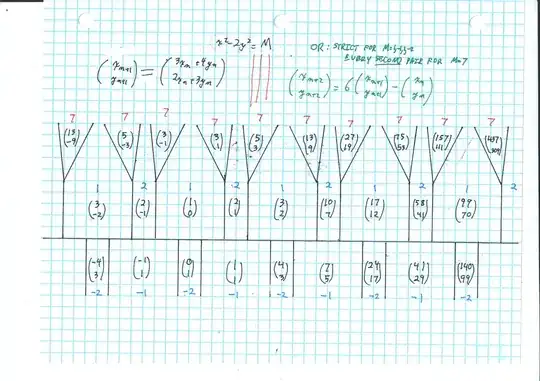

I want to prove the algorithm below produces all solutions of $x^2-2y^2=-1$. Although this algorithms have been already posted to another posts on mathstack exchange, they don't explain why it find all solution. This is the most important (and difficult) part to prove.

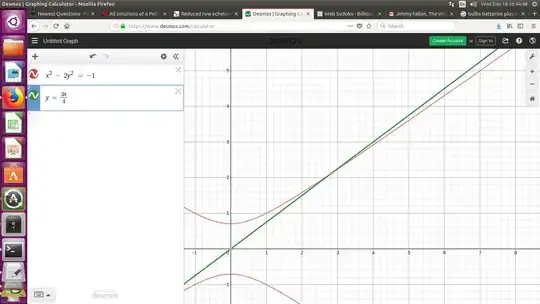

I want to get all integer solutions of $$x^2-2y^2=-1$$ for $x,y>0$. This equation is known as Pell's equation. The minimum solution is $(x,y)=(1,1)$. If we consider the norm of the element of $\mathbb{Q}[\sqrt{2}]$, any $(1+\sqrt2)^k=x_k+\sqrt2y_k$ satisfies $N(x_k+\sqrt2y_k)=N(1+\sqrt{2})^k=(-1)^k$. Thus, we get $$x_k^2-2y_k^2=(-1)^k.$$ So, $(x_{2k-1},y_{2k-1})$ is the solution of $x^2-2y^2=-1.$ I want to know if there is any other solution or to prove this is the only solution.