Added. A couple of words: you ran into trouble because you didn’t recognize that you had two ways of getting the trivial subgroup as a quotient.

In principle, the exhaustive/exhausting way of using Goursat’s Lemma to list all possible subgroups of $A\times B$ would be the following:

- Find all subgroups of $A$.

- For each subgroup $H$ of $A$, find its normal subgroups $N$.

- Make a list of the quotients $H/N$.

- Repeat with $B$.

- Identify pairs, one from each list, of isomorphic subgroups.

- List all isomorphisms between such pais.

- Each isomorphism listed yields a subgroup.

So here you would start by taking all subgroups of $C_5$, and then list all its quotients. You get: (i) trivial and all of $C_5$ for the subgroup $C_5$; and (ii) trivial for the subgroup $\{e\}$. Then do the same for $S_4$, though the fact that you are only aiming for $C_5$ and the trivial group simplify matters, as done below.

So, as you know, Goursat’s Lemma tells you all subgroups of

$C_5\times S_4$ arise from isomophisms of quotients of subgroups of

$C_5$ and

$S_4$.

So a subgroup of $C_5\times S_4$ corresponds to five pieces of information:

- A subgroup $H$ of $C_5$;

- A subgroup $K$ of $S_4$;

- A normal subgroup $N$ of $H$;

- A normal subgroup $M$ of $K$;

- An isomorphism $\phi\colon H/M\to K/N$.

The subgroup is then the “graph of $\phi$”, given by

$$\{ (x,y)\in C_5\times S_4\mid x\in H, y\in K, \phi(xM)=yN\}.$$

As you note, the only quotients of subgroups of $C_5$ are $C_5$ and $\{1\}$. But there are two ways of “getting” $\{1\}$. One is to take the trivial subgroup and quotient out by itself; the other is to take $C_5$ and quotient out by itself.

Now, every quotient of a subgroups of $S_4$ has order prime to $5$, so your isomorphism will never involve $C_5/\{e\}$ on “the left side”. Since you will always be taking the trivial subgroup on the left, that amounts to looking at any subgroup of $K$ of $S_4$, moding out by itself (that is, $M=K$), and identifying it with the trivial subgroup on the right in either of the two ways of getting it. You will have either the trivial isomorphism $\phi\colon C_5/C_5\to K/K$, or the trivial isomorphism $\phi\colon \{e\}/\{e\} \to K/K$.

So you end up with two types of subgroups:

- Those that are obtained by taking $H=C_5$, $N=H$, $K$ a subgroup of $S_4$, and $M=K$. The corresponding subgroup is

$$\{ (x,y)\in C_5\times S_4\mid y\in K\} = C_5\times K.$$

- Those that are obtained by taking $H=\{e\}$, $N=\{e\}$, $K$ a subgroup of $S_4$, and $M=K$. The corresponding subgroup is

$$\{ (x,y)\in C_5\times S_4\mid x=e, y\in K\} = \{e\}\times K.$$

The trivial subgroup is obtained in Type 2, when you take $K=\{e\}=M$.

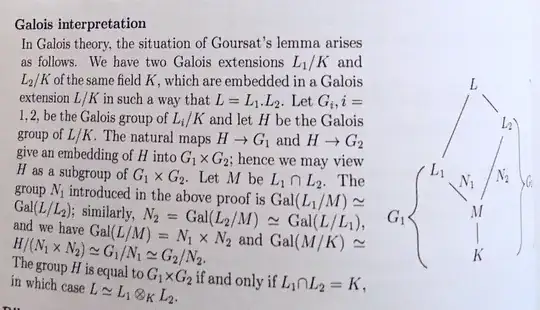

Here’s two trivial examples in Galois Theory.

Consider the extension $L=\mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{2},\sqrt{3})$ over $\mathbb{Q}$. You have the intermediate extensions $L_1=\mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{2})$, with Galois group $C_2$ over $\mathbb{Q}$, and $L_2=\mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{3})$ with Galois group $C_3$. Thus, the Galois group of $L$ over$\mathbb{Q}$ embedds into $C_2\times C_2$; because $L_1\cap L_2=\mathbb{Q}$, so we get $\mathrm{Gal}(L/\mathbb{Q}) = C_2\times C_2$.

Now consider $L$, the splitting field of $(x^4-2)(x^4-3)$ over $\mathbb{Q}$, with $L_1$ the splitting field of $x^4-2$ and $L_2$ the splitting field of $x^4-3$. Each of them is obtained by first adding $i$ and then adding $\sqrt[4]{r}$, with $r=2$ and $3$, giving you a dihedral group of order $8$. Thus, the Galois group of $L/\mathbb{Q}$ is a subdirect product of $D_4\times D_4$ (with $D_n$ the dihedral group of degree $n$ and order $2n$). In this case, $M=L_1\cap L_2=\mathbb{Q}(i)$, so you do not get the whole direct product. Instead, note that $\mathrm{Gal}(L_i/M)$ is cyclic of order $4$. So $\mathrm{Gal}(L/M) \cong C_4\times C_4$ with $\mathrm{Gal}(M/\mathbb{Q}) \cong C_2$. The group $\mathrm{Gal}(L/\mathbb{Q})$ is a subdirect product of $D_4\times D_4$, given by taking the cyclic group of order $4$ in each copy, and taking the graph of the identity isomorphism of $(D_4/C_4)\times(D_4/C_4)$.